Source: The Conversation – USA – By Mike Chapple, Teaching Professor of IT, Analytics, and Operations, University of Notre Dame

Cybersecurity and data privacy are constantly in the news. Governments are passing new cybersecurity laws. Companies are investing in cybersecurity controls such as firewalls, encryption and awareness training at record levels.

And yet, people are losing ground on data privacy.

In 2024, the Identity Theft Resource Center reported that companies sent out 1.3 billion notifications to the victims of data breaches. That’s more than triple the notices sent out the year before. It’s clear that despite growing efforts, personal data breaches are not only continuing, but accelerating.

What can you do about this situation? Many people think of the cybersecurity issue as a technical problem. They’re right: Technical controls are an important part of protecting personal information, but they are not enough.

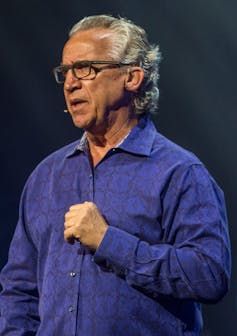

As a professor of information technology, analytics and operations at the University of Notre Dame, I study ways to protect personal privacy.

Solid personal privacy protection is made up of three pillars: accessible technical controls, public awareness of the need for privacy, and public policies that prioritize personal privacy. Each plays a crucial role in protecting personal privacy. A weakness in any one puts the entire system at risk.

The first line of defense

Technology is the first line of defense, guarding access to computers that store data and encrypting information as it travels between computers to keep intruders from gaining access. But even the best security tools can fail when misused, misconfigured or ignored.

Two technical controls are especially important: encryption and multifactor authentication. These are the backbone of digital privacy – and they work best when widely adopted and properly implemented.

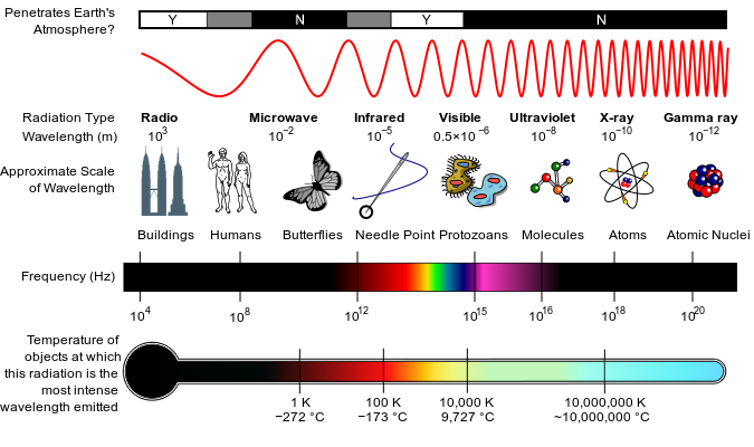

Encryption uses complex math to put sensitive data in an unreadable format that can only be unlocked with the right key. For example, your web browser uses HTTPS encryption to protect your information when you visit a secure webpage. This prevents anyone on your network – or any network between you and the website – from eavesdropping on your communications. Today, nearly all web traffic is encrypted in this way.

But if we’re so good at encrypting data on networks, why are we still suffering all of these data breaches? The reality is that encrypting data in transit is only part of the challenge.

Securing stored data

We also need to protect data wherever it’s stored – on phones, laptops and the servers that make up cloud storage. Unfortunately, this is where security often falls short. Encrypting stored data, or data at rest, isn’t as widespread as encrypting data that is moving from one place to another.

While modern smartphones typically encrypt files by default, the same can’t be said for cloud storage or company databases. Only 10% of organizations report that at least 80% of the information they have stored in the cloud is encrypted, according to a 2024 industry survey. This leaves a huge amount of unencrypted personal information potentially exposed if attackers manage to break in. Without encryption, breaking into a database is like opening an unlocked filing cabinet – everything inside is accessible to the attacker.

Multifactor authentication is a security measure that requires you to provide more than one form of verification before accessing sensitive information. This type of authentication is more difficult to crack than a password alone because it requires a combination of different types of information. It often combines something you know, such as a password, with something you have, such as a smartphone app that can generate a verification code or with something that’s part of what you are, like a fingerprint. Proper use of multifactor authentication reduces the risk of compromise by 99.22%.

While 83% of organizations require that their employees use multifactor authentication, according to another industry survey, this still leaves millions of accounts protected by nothing more than a password. As attackers grow more sophisticated and credential theft remains rampant, closing that 17% gap isn’t just a best practice – it’s a necessity.

Multifactor authentication is one of the simplest, most effective steps organizations can take to prevent data breaches, but it remains underused. Expanding its adoption could dramatically reduce the number of successful attacks each year.

Awareness gives people the knowledge they need

Even the best technology falls short when people make mistakes. Human error played a role in 68% of 2024 data breaches, according to a Verizon report. Organizations can mitigate this risk through employee training, data minimization – meaning collecting only the information necessary for a task, then deleting it when it’s no longer needed – and strict access controls.

Policies, audits and incident response plans can help organizations prepare for a possible data breach so they can stem the damage, see who is responsible and learn from the experience. It’s also important to guard against insider threats and physical intrusion using physical safeguards such as locking down server rooms.

Public policy holds organizations accountable

Legal protections help hold organizations accountable in keeping data protected and giving people control over their data. The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation is one of the most comprehensive privacy laws in the world. It mandates strong data protection practices and gives people the right to access, correct and delete their personal data. And the General Data Protection Regulation has teeth: In 2023, Meta was fined €1.2 billion (US$1.4 billion) when Facebook was found in violation.

Despite years of discussion, the U.S. still has no comprehensive federal privacy law. Several proposals have been introduced in Congress, but none have made it across the finish line. In its place, a mix of state regulations and industry-specific rules – such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act for health data and the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act for financial institutions – fill the gaps.

Some states have passed their own privacy laws, but this patchwork leaves Americans with uneven protections and creates compliance headaches for businesses operating across jurisdictions.

The tools, policies and knowledge to protect personal data exist – but people’s and institutions’ use of them still falls short. Stronger encryption, more widespread use of multifactor authentication, better training and clearer legal standards could prevent many breaches. It’s clear that these tools work. What’s needed now is the collective will – and a unified federal mandate – to put those protections in place.

This article is part of a series on data privacy that explores who collects your data, what and how they collect, who sells and buys your data, what they all do with it, and what you can do about it.

![]()

Mike Chapple does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Your data privacy is slipping away – here’s why, and what you can do about it – https://theconversation.com/your-data-privacy-is-slipping-away-heres-why-and-what-you-can-do-about-it-251768