Source: The Conversation – USA – By Julie Novkov, Professor of Political Science and Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies, University at Albany, State University of New York

Legal battles over President Donald Trump’s executive order to end birthright citizenship continued on July 10, 2025, after a New Hampshire federal district judge issued a preliminary injunction that will, if it’s not reversed, prevent federal officials from enforcing the order nationally.

The ruling by U.S. District Judge Joseph Laplante, a George W. Bush appointee, asserts that this policy of “highly questionable constitutionality … constitutes irreparable harm.”

In its ruling in late June, the Supreme Court allowed the Trump administration to deny citizenship to infants born to undocumented parents in many parts of the nation where individuals or states had not successfully sued to prevent implementation – including a number of mid-Atlantic, Midwest and Southern states.

Trump’s executive order limits U.S. citizenship by birth to those who have at least one parent who is a U.S. citizen or legal permanent resident. It denies citizenship to those born to undocumented people within the U.S. and to the children of those on student, work, tourist and certain other types of visas.

The preliminary injunction is on hold for seven days to allow the Trump administration to appeal.

The June 27 Supreme Court decision on birthright citizenship limited the ability of lower-court judges to issue universal injunctions to block such executive orders nationwide.

Laplante was able to avoid that limit on issuing a nationwide injunction by certifying the case as a class action lawsuit encompassing all children affected by the birthright order, following a pathway suggested by the Supreme Court’s ruling.

Pathways beyond universal injunctions

In its recent birthright citizenship ruling, Trump v. CASA, the Supreme Court noted that plaintiffs could still seek broad relief by filing such class action lawsuits that would join together large groups of individuals facing the same injury from the law they were challenging.

And that’s what happened.

Litigants filed suit in New Hampshire’s district court the same day that the Supreme Court decided CASA. They asked the court to certify a class consisting of infants born on or after Feb. 20, 2025, who would be covered by the order and their parents or prospective parents. The court allowed the suit to proceed as a class action for these infants.

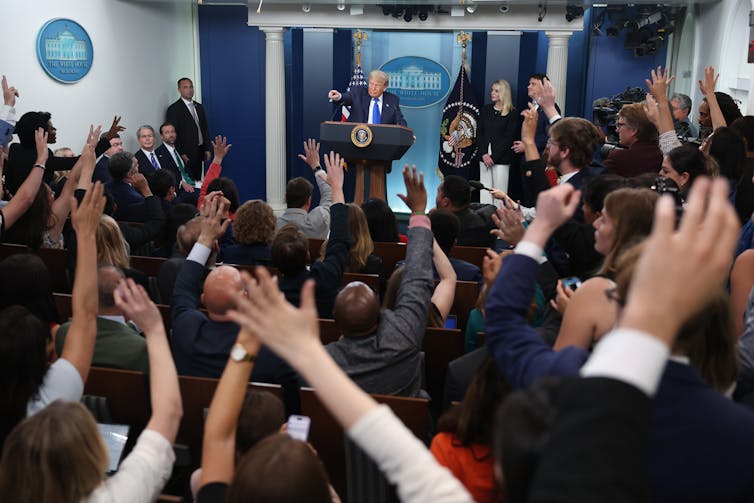

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

What if this injunction doesn’t stick?

If the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit or the Supreme Court invalidates the New Hampshire court’s newest national injunction and another injunction is not issued in a different venue, the order will then go into effect anywhere it is not currently barred from doing so. Implementation could begin in as many as 28 states where state attorneys general have not challenged the Trump birthright citizenship policy if no other individuals or groups secure relief.

As political science scholars who study race and immigration policy, we believe that, if implemented piecemeal, Trump’s birthright citizenship order would create administrative chaos for states determining the citizenship status of infants born in the United States. And it could lead to the first instances since the 1860s of infants being born in the U.S. being denied citizenship categorically.

States’ role in establishing citizenship

Almost all U.S.-born children are issued birth certificates by the state in which they are born.

The federal government’s standardized form, the U.S. standard certificate of live birth, collects data on parents’ birthplaces and their Social Security numbers, if available, and provides the information states need to issue birth certificates.

But it does not ask questions about their citizenship or immigration status. And no national standard exists for the format for state birth certificates, which traditionally have been the simplest way for people born in the U.S. to establish citizenship.

If Trump’s executive order goes into effect, birth certificates issued by local hospitals would be insufficient evidence of eligibility for federal government documents acknowledging citizenship. The order would require new efforts, including identification of parents’ citizenship status, before authorizing the issuance of any federal document acknowledging citizenship.

Since states control the process of issuing birth certificates, they will respond differently to implementation efforts. Several states filed a lawsuit on Jan. 21 to block the birthright citizenship order. And they will likely pursue an arsenal of strategies to resist, delay and complicate implementation.

While the Supreme Court has not yet confirmed that these states have standing to challenge the order, successful litigation could bar implementation in up to 18 states and the District of Columbia if injunctions are narrowly framed, or nationally if lawyers can persuade judges that disentangling the effects on a state-by-state basis will be too difficult.

Other states will likely collaborate with the administration to deny citizenship to some infants. Some, like Texas, had earlier attempted to make it particularly hard for undocumented parents to obtain birth certificates for their children.

Matt McClain/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Potential for chaos

If the Supreme Court rejects attempts to block the executive order nationally again, implementation will be complicated.

That’s because it would operate in some places and toward some individuals while being legally blocked in other places and toward others, as Justice Sonia Sotomayor warned in her Trump v. CASA dissent.

Children born to plaintiffs anywhere in the nation who have successfully sued would have access to citizenship, while other children possibly born in the same hospitals – but not among the groups named in the suits – would not.

Babies born in the days before implementation would have substantially different rights than those born the day after. Parents’ ethnicity and countries of origin would likely influence which infants are ultimately granted or denied citizenship.

That’s because some infants and parents would be more likely to generate scrutiny from hospital employees and officials than others, including Hispanics, women giving birth near the border, and women giving birth in states such as Florida where officials are likely to collaborate enthusiastically with enforcement.

The consequences could be profound.

Some infants would become stateless, having no right to citizenship in another nation. Many people born in the U.S. would be denied government benefits, Social Security numbers and the ability to work legally in the U.S.

With the constitutionality of the executive order still unresolved, it’s unclear when, if ever, some infants born in the U.S. will be the first in the modern era to be denied citizenship.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. How citizenship chaos was averted, for now, by a class action injunction against Trump’s birthright citizenship order – https://theconversation.com/how-citizenship-chaos-was-averted-for-now-by-a-class-action-injunction-against-trumps-birthright-citizenship-order-260175