Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Cora Sutherland, Interim Assistant Director, Center for Water Policy, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Offshore wind power could provide far more electricity than the U.S. uses for residential, commercial and industrial purposes. But the federal government has recently stopped approving offshore projects in the ocean.

Another option is available, though: the Great Lakes, where we are based as water policy researchers, and where state agencies rather than federal officials are the trustees of the lakes. A January 2025 executive order from President Donald Trump attempts to stop all federal permits for offshore and onshore wind power pending a review of federal wind leasing and permitting practices.

But the states, not the federal government, handle leases and permits for wind power on the Great Lakes, though federal agencies are involved in the overall process. It is unclear how this executive order might impede federal action, but at the very least states could lay the groundwork now to be prepared to act when the next shift in federal priorities arrives.

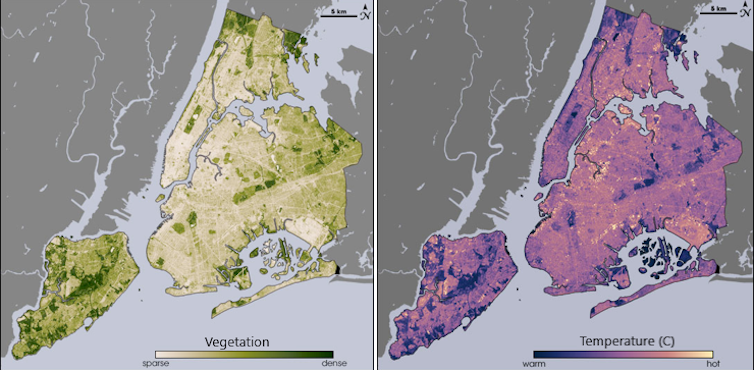

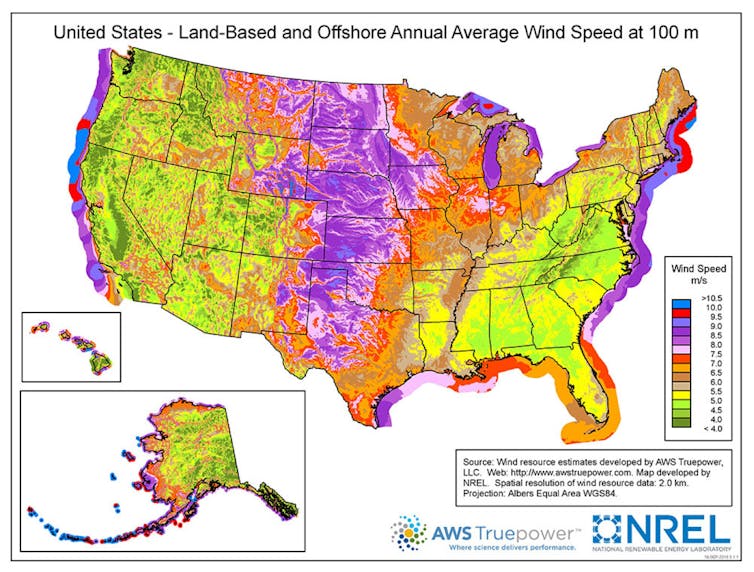

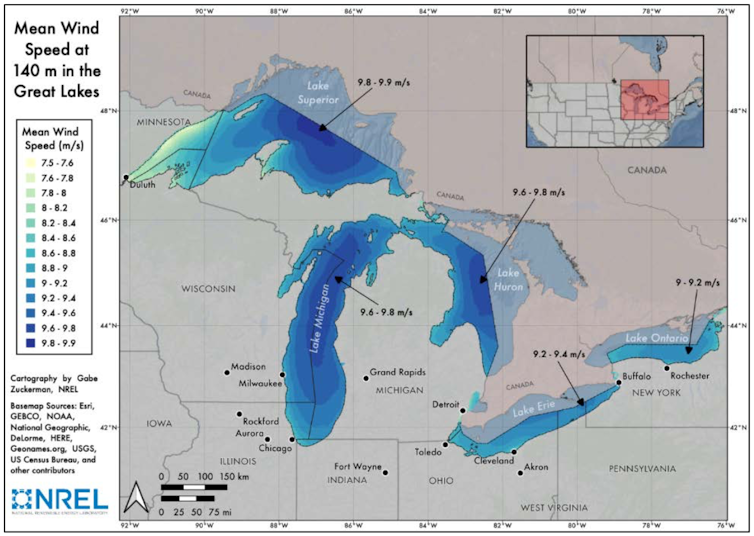

A 2023 analysis from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory found that the Great Lakes states have enough offshore wind power potential to provide three times as much electricity as all eight Great Lakes states use currently, which would mean plenty left over to meet increasing demand or send power elsewhere in the country.

States are looking for opportunities

States have been forging their own paths separate from federal clean energy policy for decades. All eight Great Lakes states have state clean energy goals, and five of them – Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, New York and Wisconsin – have a goal to achieve 100% clean or renewable energy by 2040 or 2050.

The challenge is not just to transform the current energy supply. As transportation and other sectors electrify, that increases electricity demand. As artificial intelligence proliferates, tech companies need more and more electricity and water for their data centers. By 2028, data centers are projected to consume nearly 12% of the country’s total usage, which requires massive increases in production in the Great Lakes and other key locations.

Companies and states are looking high and low to find enough electricity to meet the rising demand. They are extending the lives of coal-fired power plants and building new gas-fired power plants. Elon Musk’s xAI company has even been powering an artificial intelligence data center in Tennessee with massive generators that add air pollution without permits.

Government and industry are also looking to other sources, such as investing in nuclear fusion advancement and building geothermal plants.

A brief history

In the 2000s and 2010s, the Great Lakes Commission Wind Collaborative, Wisconsin Public Service Commission and the Michigan Great Lakes Wind Council began to sketch out regulations for offshore wind in the Great Lakes and to identify locations that might be suitable for the turbines.

In 2012, the Obama administration agreed to collaborate with five Great Lakes states – Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, New York and Pennsylvania – to streamline a permitting process for offshore wind development. Multiple projects were proposed off the shores of Michigan, Ohio and Ontario, Canada, though Ontario banned offshore wind projects in 2011.

Since then, momentum has stalled. One effort, the Icebreaker project off Cleveland, was approved and survived various legal challenges, but the project backers paused it indefinitely in 2023 due to the economic impacts of the legal delays.

Community activists are split, with some embracing offshore wind in the Great Lakes as part of a clean energy future and others vocally opposing it, citing environmental, health and economic concerns.

As of mid-2025, the Great Lakes were home to no offshore wind turbines.

National Renewable Energy Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy

Big potential, big unknowns

States continue to explore the possibility of offshore wind power in the Great Lakes. In early 2025, Illinois legislators again introduced a bill to create a pilot wind project off Chicago in Lake Michigan.

Also in 2025, Pennsylvania legislators introduced a bill to facilitate offshore wind power in Lake Erie. If adopted, the law would map which areas are fit to be leased for development by avoiding nearshore areas, shipping lanes and migration pathways. The Ontario Clean Air Alliance is pushing the province to lift its moratorium and reconsider offshore wind in Canadian waters.

A lot of details remain unknown. New York state supports offshore wind in the ocean but says “Great Lakes Wind does not provide the same electric and reliability benefits” by comparison. Ocean wind tends to be closer to areas where electricity demand is high, which can make those projects more cost-effective.

New York also concluded in 2022 that despite the combined 144.5 terawatt-hours of annual technical potential in state waters in Lake Erie and Lake Ontario, “numerous practical considerations … would need to be addressed before such projects can be successfully commercialized.”

To further explore the concerns New York’s report and others have raised, in 2024, with National Science Foundation funding, we collaborated with a team of researchers looking at a wide range of issues, including engineering, environmental effects and law. That effort resulted in articulating research questions whose answers would clarify how realistic different aspects of offshore wind could be in the Great Lakes, such as:

- How does ice that forms in freshwater affect the structural integrity of turbines?

- Are floating turbines a better fit than traditional fixed-bottom turbines to reach the higher wind speeds in the deeper parts of the lakes and out of view from shore?

- If turbine components and installation vessels can’t fit through the St. Lawrence Seaway, could they be built in the region and drive economic development?

- Can turbines be located in places that improve fisheries and avoid migratory paths of birds and bats?

- How can states establish leasing and permitting programs that maximize environmental, social and economic benefits?

Kamil Krzaczynski/AFP via Getty Images

State jurisdiction is an opportunity

In the oceans, U.S. states have jurisdiction from shore out three miles, with the federal government’s jurisdiction continuing out for hundreds of miles beyond that. So offshore project sites in the oceans are leased by the federal government.

The Great Lakes are different. The state governments hold the lakes’ waters and submerged lands in trust for the public. And state jurisdiction extends from shore all the way out to the boundary of a neighboring state’s jurisdiction or the international boundary with Canada.

Regulation of planning, site selection, leasing and other elements of offshore wind projects in the Great Lakes are the responsibility of one or another U.S. state. The federal government’s role is secondary, conducting environmental reviews and protecting navigation, but could still result in slowing state-led projects.

In research we published in 2024 and 2025, we explain that states could evaluate and select offshore wind projects based on a range of social and environmental benefits, in addition to financial considerations. For instance, they could look for designs that provide fish habitat or seek corporate partners that agree to train local workers, manufacture turbines and ships near the lakes, and provide cheaper electricity to local consumers.

Despite all the unknowns, we encourage greater support for research to harness the potential of offshore wind energy in the Great Lakes to be a renewable resource for states, the region and the nation as a whole.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Great Lakes offshore wind could power the region and beyond – https://theconversation.com/great-lakes-offshore-wind-could-power-the-region-and-beyond-261311