Source: The Conversation – USA (3) – By Ross Channing Reed, Lecturer in Philosophy, Missouri University of Science and Technology

In his powerful book “The Burnout Society,” South Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han argues that in modern society, individuals have an imperative to achieve. Han calls this an “achievement society” in which we must become “entrepreneurs” – branding and selling ourselves; there is no time off the clock.

In such a society, even leisure risks becoming another kind of work. Rather than providing rest and meaning, leisure is often competitive, performative and exhausting.

People feeling pressure to self-promote, for example, might spend their free time posting photos of an athletic race or an elaborate vacation on social media

to be viewed by family, friends and potential employers, adding to exhaustion and burnout.

As a philosopher and philosophical counselor, I study connections between unhealthy forms of leisure and burnout. I have found that philosophy can help us navigate some of the pitfalls of leisure in an achievement society. The celebrated Greek philosopher Aristotle, who lived from 384 to 322 B.C.E., in particular, can offer important insights.

Aristotle on self-development

Aristotle begins the famous “Nicomachean Ethics” by pointing out that we are all searching for happiness. But, he says, we are often confused about how to get there.

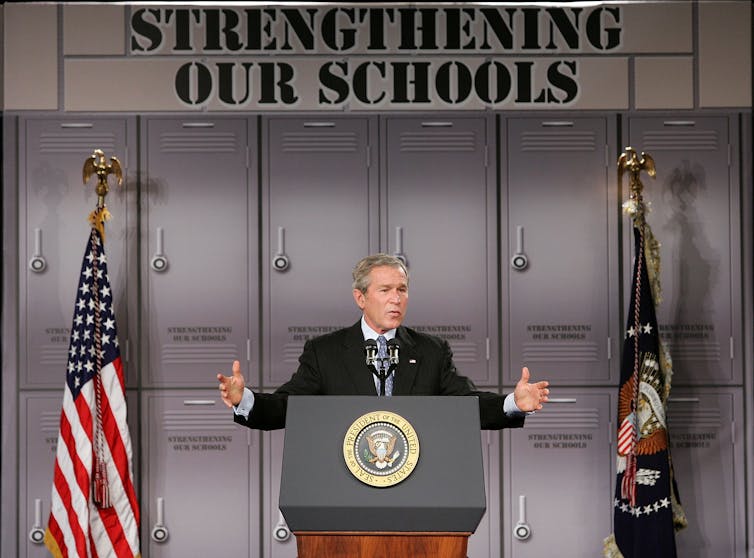

AzmanL/E+ via Getty images

Aristotle believed that pleasure, wealth, honor and power will not ultimately make us happy. True happiness, he said, required ethical self-development: “Human good turns out to be activity of soul in accordance with virtue.”

In other words, if we want to be happy, Aristotle contended, we must make reasoned choices to develop habits that, over time, become character traits such as courage, temperance, generosity and truthfulness.

Aristotle is explicitly linking the good life to becoming a certain kind of person. There is no shortcut to ethical self-development. It takes time – time off the clock, time not engaged in some kind of entrepreneurial self-promotion.

Aristotle is also telling us about the power of our choices. Habits, he argues, are not just about action, but also motives and character. Our actions, he says, actually change our desires. Aristotle says: “By abstaining from pleasures we become temperate, and it is when we have become so that we are most able to abstain from them.”

In other words, good habits are the result of moving incrementally in the right direction through practice.

For Aristotle, good habits lead to ethical self-development. The converse is also true. To this end, for Aristotle, having good friends and mentors who guide and support moral development are essential.

How Aristotle helps us understand leisure

In an achievement society, we are often conditioned to respond to external pressures to self-promote. We may instead look to pleasure, wealth, honor and power for happiness. This can sidetrack the ethical development required for true happiness.

True leisure – leisure that is not bound to the imperative to achieve – is time we can reflect on our real priorities, cultivate friendships, think for ourselves, and step back and decide what kind of life we want to live.

The Greek word “eudaimonia,” often translated simply as happiness, is the term Aristotle uses to describe human thriving and flourishing. According to philosopher Jane Hurly, Aristotle views “leisure as essential for human thriving.” Indeed, “for both Plato and Aristotle leisure … is a prerequisite for the achievement of the highest form of human flourishing, eudaimonia,” as philosopher Thanassis Samaras argues.

While we may have limited means to acquire pleasure, wealth, honor and power, Aristotle tells us that we have control over the most important variable in the good life: what kind of person we will become. Leisure is crucial because it is time in which we get to decide what kind of habits we will develop and what kind of person we will become. Will we capitulate to achievement society? Or utilize our free time to develop ourselves as individuals?

When leisure is preoccupied with entrepreneurial self-promotion, it is difficult for moral development to take place. Free time that is not hijacked by the imperative to achieve is required for the development of a consistent relationship to oneself – what I call a relationship of self-solidarity – a kind of reflective self-awareness necessary to aim at the right target and make moral choices. Without such a relationship, the good life will remain elusive.

Leisure reimagined

Rather than adopting the achievement society’s formulation of the good life, we may be able to formulate our own vision. Without one’s own vision, we risk becoming mired in bad habits, leading us away from the moral development through which the good life becomes possible.

Aristotle makes it clear that we have the power to change not only our behaviors but our desires and character. This self-development, as Aristotle writes, is a necessary part of the good life – a life of eudaimonia.

The choices we make in our free time can move us closer to eudaimonia. Or they could move us in the direction of burnout.

![]()

Ross Channing Reed does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Why leisure matters for a good life, according to Aristotle – https://theconversation.com/why-leisure-matters-for-a-good-life-according-to-aristotle-260392