Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Rebecca Corbett, Japanese Studies Librarian and Senior Lecturer in History, University of Southern California

“Matcha mania” shows no signs of slowing, with global demand pushing “supply chains to the brink,” as Australia’s ABC News reported in July 2025.

The powdered drink retains a massive following in Tokyo, where long lines of customers snake out of The Matcha Tokyo on any given Saturday. At the trendy, minimalist cafe, the staff uses a cast-iron kettle and a bamboo ladle. Both are a nod to the traditional Japanese way of preparing matcha, called “chanoyu,” which literally means “hot water for tea” but in English has been translated as “tea ceremony.”

Beyond Tokyo, matcha cafes and bars have also become a familiar sight in Western cities, from Stockholm to Melbourne to Los Angeles. Matcha has been a permanent fixture on the menu at Starbucks since 2019 and at Dunkin’ since 2020.

It’s been quite the rise for a drink long met with skepticism in the West.

World’s fairs serve as a stage

I spent part of 2024 as a Japan Foundation Fellow at Waseda University, where I researched how Westerners experienced matcha and chanoyu during the Meiji period, an era of rapid modernization and Westernization that lasted from 1868 to 1912.

Matcha is a form of green tea in which young tea leaves have been ground to a powder using a stone mill. Unlike other teas, which involve steeping leaves and removing them before drinking, matcha powder is then whisked into hot water.

Sina Schuldt/Picture Alliance via Getty Images

Matcha actually originated in China. It was introduced to Japan around 1250 C.E., where it assumed a key role in chanoyu from the 1500s on. Portuguese Jesuit missionaries in Japan in the 1500s wrote about both matcha and chanoyu. But only in the 19th century did interest in matcha really take off outside Japan.

Beginning in the late 19th century, world’s fairs and expositions started being held in European and American cities. These events allowed countries from around the world to showcase their art, inventions and culture before huge audiences.

For emerging Japan, world’s fairs and expositions presented a tremendous opportunity. In its exhibits, Japanese representatives often gave chanoyu demonstrations, while both the Japanese government and tea industry heavily marketed all varieties of Japanese green tea, including matcha.

Initial skepticism

Though steeped Japanese green tea became popular in 19th-century America, where it was usually sipped with milk and sugar, matcha didn’t initially jibe with Western palates.

Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore, an American journalist and travel writer who spent decades living in Japan, described matcha as “a bowl of green gruel more bitter than quinine” in her 1891 book “Jinrikisha Days in Japan.” Wealthy Canadian tourist Katharine Schuyler Baxter detailed her experience at a matcha tea gathering in her 1895 book “In Beautiful Japan: A Story of Bamboo Lands.”

“The beverage is made of powdered leaves, is greenish in color, thick like pea-soup, fragrant, and not very palatable,” she wrote. In my research, I encountered “pea soup” being the most common descriptor of matcha at this time.

Descriptions of matcha and chanoyu also abound in newspaper articles from the era.

Canadian journalist Helen E. Gregory-Flesher described the Japanese tea ceremony for readers in San Francisco.

“Very few Europeans can drink it without feeling very unhappy,” she wrote of a thick preparation of matcha called “koicha.” “For in the first place the taste is not agreeable, and then it is so intensely strong that it is sure to disagree with them if they do manage to swallow it.”

For the St. Louis Globe Democrat, the Countess Anna de Montaigu reported on a tea gathering she attended at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. She described matcha’s flavor as “exquisite,” but left her American readers with a warning: “Drunk without sugar or cream, this expensive tea … is not pleasant to the palate of the uninitiated.”

Embracing the ceremony

There are also records of a few Westerners studying chanoyu while living in Japan. While those records don’t include their thoughts on matcha, I have to assume they enjoyed drinking it – at least enough to continue their practice, since in all cases they studied chanoyu for several years.

Chanoyu isn’t a simple serving ceremony. It’s a practice that involves learning the range of ways to serve and receive matcha, as well as food, and it’s taught by various “lineages,” or schools.

Lessons involve students learning how to be a host and a guest through observation and practice. All of this learning is put into practice by hosting or being a guest at a formal tea gathering, called a “chaji.” This can last three to four hours and include a multicourse meal – the “kaiseki” – several rounds of sake, and the laying and replenishing of charcoal.

There are two servings of matcha; one is prepared as thick tea – koicha – the other as thinner tea known as “usucha.” Each is accompanied by sweets.

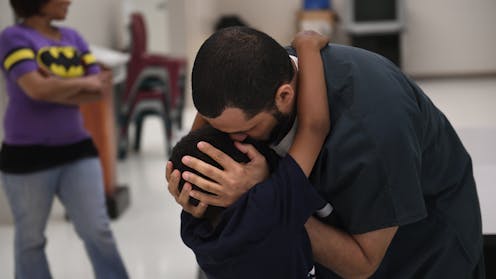

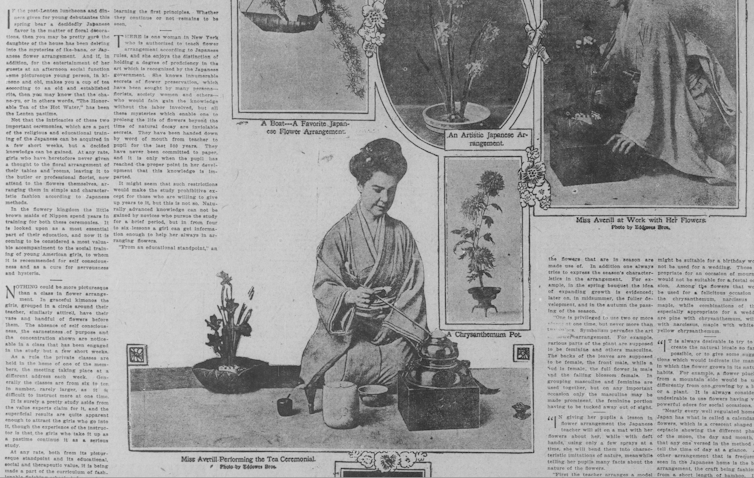

A Swedish woman named Ida Trotzig lived in Japan from 1888 to 1921, during which she took lessons in chanoyu. Upon returning to Sweden she published a book about chanoyu in 1911, “Cha-no-yu Japanernas teceremoni.” American Mary Averil also studied both chanoyu and ikebana, the art of Japanese flower arrangement.

Library of Congress

In 1905, the Urasenke School of Tea in Kyoto welcomed three American sisters, Helen, Grace and Florence Scottfield, as students. There, they studied under the head of the school, and a photograph of all three girls wearing kimonos with their hair styled in a Japanese manner appeared in an issue of the school’s monthly magazine in 1908.

Matcha minus chanoyu

Scholars haven’t pinpointed the reasons for the recent global matcha boom. But I think it’s worth considering a few factors.

First, it’s clear that social media, particularly Instagram and TikTok, have played a big role. The bright green beverage is aesthetically pleasing. Its many purported health benefits have also allowed it to join the ranks of other viral superfoods, such as acai berries and kombucha.

Then there’s the way Westerners often mythologize Japan as a source of “ancient wisdom.” Accompanying that is a particular infatuation with traditional Japanese practices, lifestyles and foods – matcha included.

Finally, people seem drawn to the minimalist aesthetics associated with chanoyu, which have echoes in other Japanese practices such as dry rock gardening and calligraphy.

Natasha Breen/REDA/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Interestingly, the vast majority of matcha drinkers today don’t experience chanoyu, even as matcha purveyors borrow from the practice’s aesthetics. In the late 19th century, you couldn’t drink matcha without first experiencing chanoyu. And the drink was always served “straight” – no milks, flavorings or sweeteners.

Sometimes I wonder what the Countess de Montaigu would order if she visited Pipers Tea and Coffee, which is rated the best matcha in St. Louis on Yelp. Would she prefer it straight? Or would she be won over by its In Bloom Latte – a vanilla matcha latte topped with cherry blossom-sakura cold foam?

![]()

Rebecca Corbett receives funding from The Japan Foundation. She is affiliated with the Urasenke School of Tea through membership in the Urasenke Tankokai Los Angeles Association.

– ref. Green gruel? Pea soup? What Westerners thought of matcha when they tried it for the first time – https://theconversation.com/green-gruel-pea-soup-what-westerners-thought-of-matcha-when-they-tried-it-for-the-first-time-263014