Source: The Conversation – USA – By Timothy J Lombardo, Associate Professor of History, University of South Alabama

In August 2025, the city of Philadelphia agreed to return a statue of Frank Rizzo to the supporters that commissioned the memorial in 1992.

The 2,000-pound bronze tribute to the former police commissioner-turned-mayor had stood in front of the city’s Municipal Services Building from 1998 until 2020, when then-mayor Jim Kenney ordered it removed days after protesters attempted to topple it during the protests that followed the murder of George Floyd.

While the agreement states that the statue cannot be placed in public view, conservatives have still hailed its return as a triumph for Rizzo’s legacy. In the ongoing culture wars over historical memory and memorialization, Rizzo’s supporters have declared their repossession of the statue a victory over the “woke mayor” who unlawfully removed it.

As a historian and native Philadelphian, I have written extensively about the city. My first book, which will be rereleased with a new preface in February 2026, traces the rise of Rizzo’s political appeal and contextualizes his supporters’ politics in the broader history of the rise of the right.

My work recognizes Rizzo not only as the quintessential backlash politician of the 1960s and 1970s, but also as a harbinger of today’s identity-based populism that favors social and cultural victories over economic redistribution.

As police commissioner from 1967 to 1971 and mayor from 1972 to 1979, Rizzo became a hero to the white, blue-collar Philadelphians who clamored for “law and order” and railed against liberal policymaking. Until he died in 1991, while running a third campaign to retake the mayor’s office, Rizzo was an avatar of what I call “blue-collar conservatism.”

Understanding Rizzo’s career and political popularity can help explain the persistent appeal of this identity-based populism in the 21st century.

Bastiaan Slabbers/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Rizzo, from cop to mayor

Francis Lazzaro Rizzo was born in South Philadelphia, in the mostly Italian-American neighborhood his parents settled in after immigrating from Calabria, Italy.

In a city where police work was often a family affair, Rizzo followed his father’s footsteps into the Philadelphia Police Department a few years after dropping out of high school.

Early on, he drew praise from superiors for his clean-cut image and aggressive policing. In the 1950s, Rizzo fortified that reputation while patrolling predominantly Black neighborhoods in West Philadelphia and leading raids on gay meeting places in Center City.

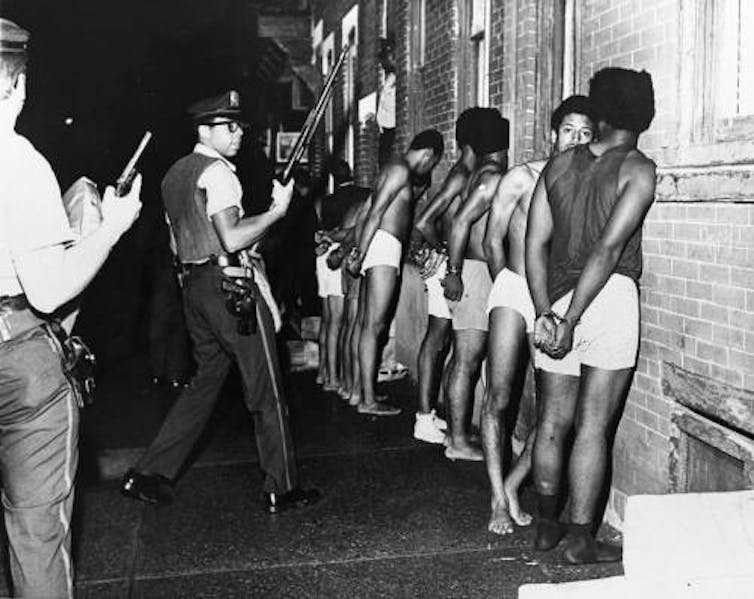

As deputy commissioner in the 1960s, Rizzo directly confronted the city’s civil rights movement. Among other exploits, he commanded the response to the Columbia Avenue Uprising in 1964, when North Philadelphia residents responded to an all-too-common act of police brutality with three days of urban disorder.

He also faced down protesters seeking to integrate Girard College, an all-white city-operated boarding school for orphaned boys in the heart of predominantly Black North Philadelphia.

While serving as acting commissioner in 1967, Rizzo led a throng of baton-wielding police into a crowd of high schoolers demanding education reform. The scene ended with police chasing down and beating mostly Black youngsters in front of the Board of Education headquarters.

Rizzo was promoted to commissioner later that year.

While African Americans and white liberals decried his “Gestapo tactics,” Rizzo grew increasingly popular among the city’s white, blue-collar residents.

Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA.

He capitalized on their enthusiasm in 1971, when he campaigned and won his first election for mayor as both a Democrat and the self-proclaimed “toughest cop in America.”

For two terms he rewarded his supporters by opposing and limiting liberal programs they had fought, like public housing, school desegregation and affirmative action. When dissatisfied Democrats challenged his reelection in 1975, Rizzo vowed revenge by saying he would “make Atilla the Hun look like a fa—t.”

Finally, while campaigning for an amendment to Philadelphia’s Home Rule Charter to allow him to run for a third consecutive mayoral term, Rizzo told an all-white audience of public housing opponents to “vote white” for charter change.

Populism then and now

Rizzo’s record makes clear why protesters targeted his statue in 2020. When Mayor Kenney ordered it removed, he called it “a deplorable monument to racism, bigotry and police brutality for members of the Black community, the LGBTQ community and many others.”

While Rizzo and his supporters were certainly part of the late 1960s backlash against civil rights and liberalism generally, his populism was more complex and durable than that narrative suggests.

He also offered affirmation to a beleaguered white, blue-collar identity. His supporters raved about his forceful policing and cheered his anti-liberalism as a last line of defense against policies they considered threats to their livelihoods. Just as important, they saw themselves reflected in the rough-talking high school dropout who worked his way up to the most powerful position in Philadelphia.

When Rizzo first ran for mayor, one of his supporters told a reporter that “He’ll win because he isn’t a Ph.D. He’s one of us. Rizzo came up the hard way.”

That kind of identity-based populism offered social and cultural victories even when it did little to address the declining economy that struck urban America in the 1970s. So while Rizzo’s populism had few answers for deindustrialization, in 1972 he was able to temporarily halt construction on a public housing project in an all-white section of his native South Philadelphia.

Dick Swanson/The Chronicle Collection via Getty Images

Trump’s similar appeal

Donald Trump offers a similar populist appeal in the 21st century. In fact, he has drawn comparisons to Rizzo since his first presidential campaign.

Like Rizzo, Trump’s appeal is more social and cultural than economic. Critics have argued that Trump’s promotion of traditional Republican economic policies belie the notion that he is a populist. Trump’s populism, however, lies not in his ability to deliver working-class prosperity, but conservative victories in the nation’s long-standing culture wars.

Trump’s policies may not fulfill his promise to lower the cost of groceries or health care, but mass deportations reward those who fear a changing American identity.

Sending troops into cities may not address the cost-of-living crisis, but it delights those who see disorder in urban society.

Trump’s attempt to recast national history museums in a patriotic mold may not usher in a new “Golden Age of America,” but it promises a victory to opponents of “woke” history.

AP Photo/Matt Rourke

Redistributive vs. identity populism

Despite the lopsided attention Trump’s social and cultural populism receives, a kind of progressive, redistributive populism persists in many American cities. This populism promises a redirection of resources from elites and toward working people.

In Philadelphia in 2023, the multicultural, left-populist Working Families Party won the two at-large seats reserved for minority-party representation in the city’s legislature. Currently, Zohran Mamdani’s upstart campaign for mayor of New York seems to be reviving a long tradition of progressive urban populism.

Redistributive populism, however, remains at odds with the identity populism once championed by Rizzo and now by Trump. While the Trump administration’s policies may promise social and cultural victories, they have done little to affect the economic prospects of working-class Americans.

Read more of our stories about Philadelphia.

![]()

Timothy J Lombardo does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. How Frank Rizzo, a high school dropout, became Philadelphia’s toughest cop and a harbinger of MAGA politics – https://theconversation.com/how-frank-rizzo-a-high-school-dropout-became-philadelphias-toughest-cop-and-a-harbinger-of-maga-politics-263229