Source: The Conversation – USA – By Luke William Hunt, Associate Professor of Philosophy, University of Alabama

A federal judge ruled on Sept. 2, 2025, that the Trump administration broke federal law by sending National Guard troops to Los Angeles in June in response to protests over immigration raids.

In his ruling, U.S. District Judge Charles Breyer said that National Guard troops in Los Angeles had received improper training on the legal scope of their authority under federal law. He ruled that the president’s order for the troops to engage in “domestic military law enforcement” violated the Posse Comitatus Act, which – with limited exceptions – bars the use of the military in civilian law enforcement.

While he did not require the remaining soldiers to leave Los Angeles, Breyer called on the administration to refrain from using them “to execute laws.”

The Los Angeles case, President Donald Trump’s deployment of National Guard troops to fight crime in Washington, D.C., and his recent vow to send the Guard to Chicago and Baltimore to fight crime blur practical and philosophical lines erected in both law and longtime custom between the military and the police.

As a policing scholar and former FBI special agent, I believe the plan to continue using National Guard troops to reduce crime in cities such as Chicago and Baltimore violates the legal prohibition against domestic military law enforcement.

Limited law enforcement function

State and local police training focus on law enforcement and maintaining order. Community policing, which is a collaboration between police and

the community to solve problems, and the use-of-force continuum – the escalating series of appropriate actions an officer may take to resolve a situation – also form part of training.

In contrast, the goal of National Guard basic combat training is to “learn the skills it takes to become a Soldier.”

The initial 10-week training program for National Guard recruits includes learning skills such as the use of M16 military assault rifles and grenade launchers. It also includes learning guerrilla warfare tactics, as well as tactics for neutralizing improvised explosive devices while engaging in military operations. While valuable in a military setting, such activities aren’t part of domestic policing and law enforcement.

While the National Guard has, by law, a limited law enforcement function in times of domestic emergencies, it’s a unique part of the U.S. military that typically responds – at the request of a state’s governor – to natural disasters and extreme violence.

Although rare, presidents can also call up the Guard, with or without the assent of a state governor. In 1992, for example, President George H.W. Bush sent Guard troops to Los Angeles – with the California governor’s approval – to quell widespread riots following the acquittal of white police officers who had been charged with assaulting Rodney King, a Black man.

But sending soldiers who are not well versed in policing increases the likelihood of mistakes. One of the most well-known examples is the Kent State shootings on May 4, 1970, when National Guardsmen sent to the university by Ohio’s governor opened fire and killed four unarmed students during an anti-war protest on campus.

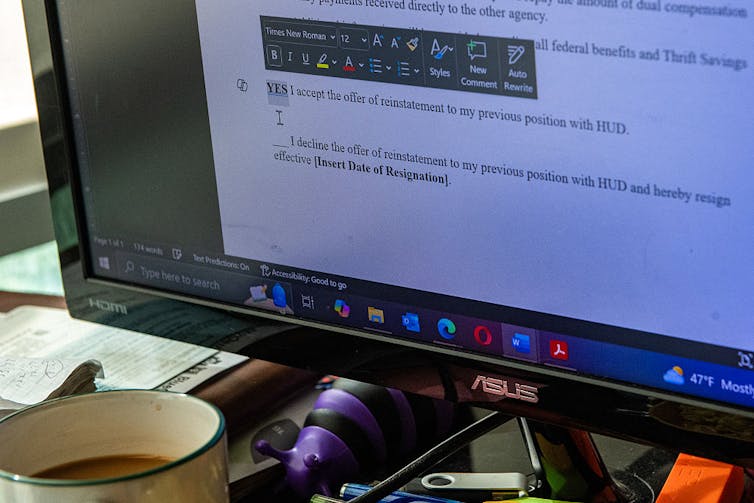

Ted Soqui/Corbis via Getty Images

The erosion of restraint

U.S. presidents have historically exercised restraint in deploying military personnel to suppress domestic unrest. Presidents typically work with state governors who request federal assistance during times of crisis.

Thousands of National Guard troops were sent to multiple states at the request of state governors following Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Among other tasks, President Barack Obama’s administration directed the Department of Defense to support FEMA’s efforts to restore power to thousands of homes.

The last time a president bypassed a state’s governor in sending the National Guard to quell civil unrest was in Selma, Alabama, in 1965. President Lyndon B. Johnson deployed the National Guard to protect civil rights protesters without the cooperation of Alabama Gov. George Wallace, a prominent segregationist.

Trump is changing this precedent by sending National Guard troops to Los Angeles, despite the fact that Gov. Gavin Newsom neither refused to follow federal law nor requested military support. In June 2025, Trump overrode Newsom and sent Guard troops to shield federal agents with Immigration and Customs Enforcement from political protests.

The decision to send federal troops to a political protest in Los Angeles has raised core legal questions. The First Amendment’s protection of the right to political protest is a pillar of U.S. jurisprudence.

‘Federalizing’ the Guard

The governed have a right to hold the government accountable and ensure that the government’s power reflects the consent of the governed.

The right to protest, of course, does not extend to criminal behavior. But the use of military personnel raises a pressing question: Is the president justified in sending military personnel to address pockets of criminality, instead of relying on state or local police?

One of a president’s legal avenues is to use a federal statute to do what’s called “federalizing” the National Guard. This means troops are temporarily transitioned from state to federal military control.

What is unique about the deployment in California is that Newsom objected to Trump’s decision to federalize troops. California in June 2025 sued the Trump administration, arguing the president unlawfully bypassed the governor when he federalized the National Guard.

On Sept. 4, 2025, Washington, D.C., sued the Trump administration on similar grounds. The lawsuit follows Trump’s decision in August to deploy hundreds of National Guard troops to police the capital.

AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana

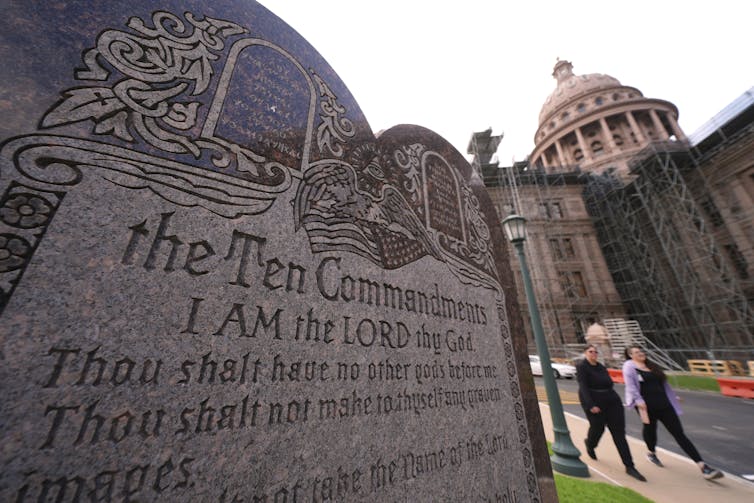

For the president to legally take control of and deploy the California National Guard under federal statutes, it was necessary for the criminality in Los Angeles to rise to a “rebellion” against the U.S.

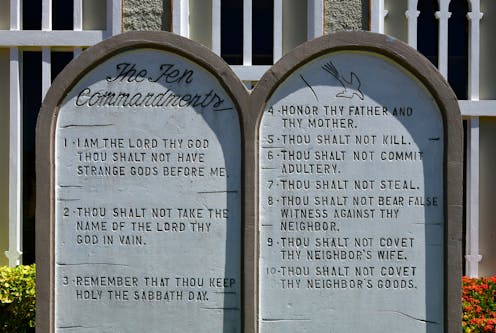

More generally, the president is prohibited from using military force – including the Marines – against civilians in pursuit of normal law-enforcement goals. This bedrock principle is based on the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878 and permits only rare exceptions, as stipulated by the Insurrection Act of 1807. This act empowers the president to deploy the U.S. military to states in circumstances relating to the suppression of an insurrection.

The Sept. 2 ruling by the federal judge in California determined that the administration deviated from these principles because the use of troops in Los Angeles did not meet the criteria established by federal law. Although the political protests in Los Angeles included some violence, the judge reasoned that the violence did not rise to a rebellion and did not prevent a traditional police response.

Federalism and the limits of executive power

In addition to the practical differences between the military and the police, there are philosophical differences derived from core principles of federalism, which refers to the division of power between the national and state governments.

In the United States, police power is derived from the 10th Amendment, which gives states the rights and powers “not delegated to the United States.” It is the states that have the power to establish and enforce laws protecting the welfare, safety and health of the public.

The use of military personnel in domestic affairs is limited by deeply entrenched policy and legal frameworks.

The deployment of National Guard troops for routine crime fighting in cities such as Los Angeles and Washington, and the proposed deployment of those troops to Chicago and Baltimore, highlights the erosion of both practical and philosophical constraints on the president and the vast federal power the president wields.

![]()

Luke William Hunt does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Trump’s deployment of the National Guard to fight crime blurs the legal distinction between the police and the military – https://theconversation.com/trumps-deployment-of-the-national-guard-to-fight-crime-blurs-the-legal-distinction-between-the-police-and-the-military-264548