Source: The Conversation – USA – By Karrin Vasby Anderson, Professor of Communication Studies, Colorado State University

In an authoritarian state, the leader engages in unconstitutional or undemocratic practices for the purpose of consolidating power.

Key components of authoritarianism include rejecting democratic rules; denying the legitimacy of opponents; tolerating or encouraging political violence; and curtailing the civil liberties of opponents.

Since he took office for a second time, President Donald Trump has sent National Guard troops to Los Angeles and Washington, named other cities run by Democrats as targets for military intervention, deployed masked and unidentifiable agents in immigration raids, explicitly threatened the city of Chicago with a military invasion and used government power to persecute his perceived political enemies.

But many journalistic outlets have yet to call him what he is – an authoritarian.

As a political communication scholar, I study how media framing shapes people’s understanding of the world.

Because authoritarianism is most visible in hindsight, people often don’t recognize it until it’s too late. Erica Chenoweth, a Harvard political scientist, notes that when it comes to democratic backsliding, “there are no bright lines … people often find out the world they’re in after the fact.”

That’s why it’s particularly important for journalists to label authoritarians as such when the evidence warrants. In Trump’s case, I believe the U.S. is well past that point.

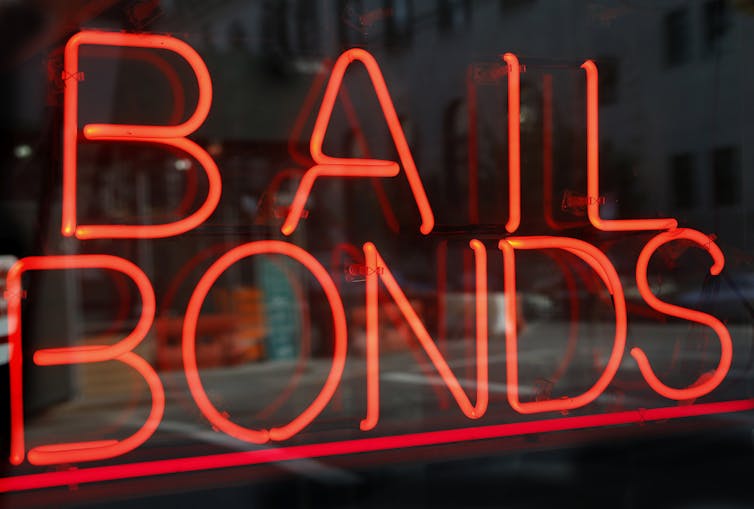

AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite

Trump’s authoritarianism

Scholars with expertise in authoritarianism have been sounding the alarm about Trump for years.

Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt’s book “How Democracies Die” describes how, during the 2016 campaign and his first presidential term, Trump exhibited the key indicators of authoritarian behavior. He undermined the legitimacy of elections Republicans lost, baselessly described his rivals as criminals, refused to unambiguously condemn violence committed by his supporters, and threatened to punish critics and members of the media.

Levitsky and Ziblatt argue that “no other major presidential candidate in modern U.S. history, including Richard Nixon, has demonstrated such a weak public commitment to constitutional rights and democratic norms.”

That intensified when Trump returned to office in 2025.

Levitsky and Lucan A. Way documented Trump’s “path to American authoritarianism” for the journal Foreign Affairs in early 2025. In March, Levitsky told New York magazine that things were going worse than even he expected, asserting, “We’re pretty screwed.”

Levitsky is not alone in that view. In a February 2025 survey of political scientists conducted by Bright Line Watch – an academic organization that researches democratic health – the percentage of scholars plummeted who said that the U.S. “mostly or fully” meets the standard for democratic health.

That was before Trump, via social media, promised to go to war in Chicago. When asked about his post, Trump said, “We’re not going to war. We’re going to clean up our cities,” but he did not back away from the intent to deploy troops against the wishes of Illinois Governor JB Pritzker.

Pritzker responded to Trump’s post by noting, “This is not a joke. This is not normal.”

On Sept. 7, 2025, New York Times opinion columnist Ezra Klein itemized some of Trump’s authoritarian actions, concluding, “This is not just how authoritarianism happens. This is authoritarianism happening.”

Truth Social Donald Trump account

What journalists have been saying

Although other opinion journalists like Jamelle Bouie, M. Gessen, Jonathan Chait and nearly every MSNBC anchor have been labeling Trump an authoritarian for some time, much hard news coverage of the Trump administration has not.

When Trump deployed troops to Washington, The Atlantic’s Quinta Jurecic dismissed it as “farcical” and “not a likely prelude to full authoritarian takeover.”

A CNN analysis similarly minimized the action as a “gambit,” a “distraction” and a “neat political trick.” CNN characterized concerns about authoritarianism as “hyperbolic warnings of looming tyranny that circulate all day on liberal media programs — whatever Trump does” and asserted that such reports “don’t really help voters understand what is going on.”

The New York Times’ Aug. 3 story by Peter Baker on Trump’s “tendency to suppress facts he doesn’t like and promote his own version of reality” bore a headline that read “Trump’s Efforts to Control Information Echo an Authoritarian Playbook,” suggesting that his actions were authoritarian without applying the label to Trump directly.

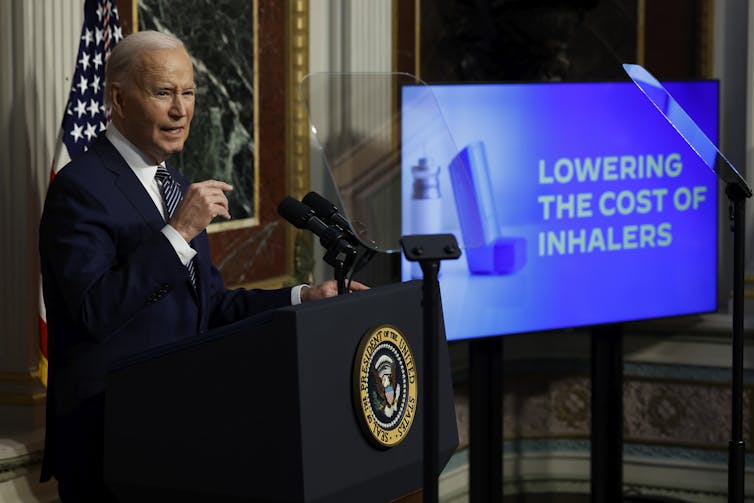

During the April 14, 2025, broadcast of CNN News Central, anchor Jessica Dean spoke with Nikolas Bowie, a Harvard Law School professor participating in a lawsuit against the Trump administration.

Bowie repeatedly called Trump an authoritarian for illegally freezing federal research funding awarded to Harvard.

When Dean noted that the “Trump administration says it’s doing all of this in an effort to combat antisemitism on campus,” Bowie responded that “antisemitism is really just a pretext for what is really an authoritarian attack on higher education.” Federal Judge Allison Burroughs later agreed with that interpretation in her ruling against the Trump administration.

Dean, however, sidestepped that interpretation, saying, “What I’m hearing is you think that enough was done to combat antisemitism, that this is about something else.”

NPR

Competitive authoritarianism

There are reasons why journalistic outlets may hesitate to identify the “something else” as authoritarianism, or portray it as a looming threat rather than a current danger.

Trump’s propensity to sue journalists, and large media corporations’ decisions to settle even when the law was on their side, have likely made journalists and editors hesitant to describe Trump as an authoritarian.

And the imperative for balance sometimes results in a “both sides-ism” that misrepresents what authoritarianism actually looks like.

When California Gov. Gavin Newsom gave a speech asserting Trump’s military response to immigration protests in California was an assault on democracy, the New York Times covered it, quoting Newsom at length about the danger Trump presented. The article also quoted Republicans who alleged that Newsom’s public health directives during the COVID-19 pandemic made him “the ultimate authoritarian.”

But the particular nature of the authoritarianism the U.S is facing in the 21st century also plays a role.

Levitsky and Way have written about “competitive authoritarianism,” a new version of authoritarianism that doesn’t look like 20th-century fascism.

Many laypeople associate the word authoritarianism with military dictatorships and totalitarian rule. In competitive authoritarian regimes, however, there’s a constant push and pull between democratic and autocratic impulses. Levitsky and Way write that elections are held, but they may not be fair. The authoritarian regime uses power gained democratically to break democratic norms, undermine democratic institutions and tilt the playing field in its own favor.

Constraining free speech

Journalistic norms of independence can pressure even ethical journalists into acquiescence to competitive authoritarianism because they want to avoid looking partisan when all coverage that falls outside the authoritarian’s approved message gets characterized as resistance.

Paramount settled what one free speech advocate described as a “widely derided lawsuit brought by Donald Trump against ’60 Minutes,’” and CBS recently pledged to stop editing recorded interviews on “Face the Nation” after complaints lodged by Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem.

The Paramount and CBS cases suggest that, left unchallenged, a competitive authoritarian leader will use their leverage to influence what should be independent journalism.

Words matter. And how a democratic society responds to its leaders can make the difference between a free society and one in which a leader increasingly suppresses the voices, rights and will of the governed.

![]()

Karrin Vasby Anderson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Why journalists are reluctant to call Trump an authoritarian – and why that matters for democracy – https://theconversation.com/why-journalists-are-reluctant-to-call-trump-an-authoritarian-and-why-that-matters-for-democracy-263778