Source: The Conversation – USA (3) – By Elizabeth Chiarello, Associate Professor of Sociology, Washington University in St. Louis

Imagine walking into your pharmacy, handing over your prescription and having it denied. Now imagine that the reason is not insufficient insurance coverage or the wrong dose, but a pharmacist who personally objects to your medication. What right does a pharmacist have to make moral decisions for their patients?

Lawmakers have wrestled with this question for decades. It reemerged in August 2025 when two pharmacists sued Walgreens and the Minnesota Board of Pharmacy, saying they had been punished after refusing to dispense gender-affirming care medications that go against their religious beliefs.

According to the pharmacists, Walgreens refused their requests for a formal religious accommodation, citing state law. One pharmacist had her hours reduced; the other was let go. If Minnesota law does not allow such an accommodation, their lawsuit argues, it violates religious freedom rights.

As a sociologist of law and medicine, I’ve spent the past 20 years studying how pharmacists grapple with tensions between their personal beliefs and employers’ demands. Framing the problem as a tension between religious freedom and patients’ rights is only one approach. Debates about pharmacists’ discretion over what they dispense also raise bigger questions about professional rights – and responsibilities.

Duty to dispense?

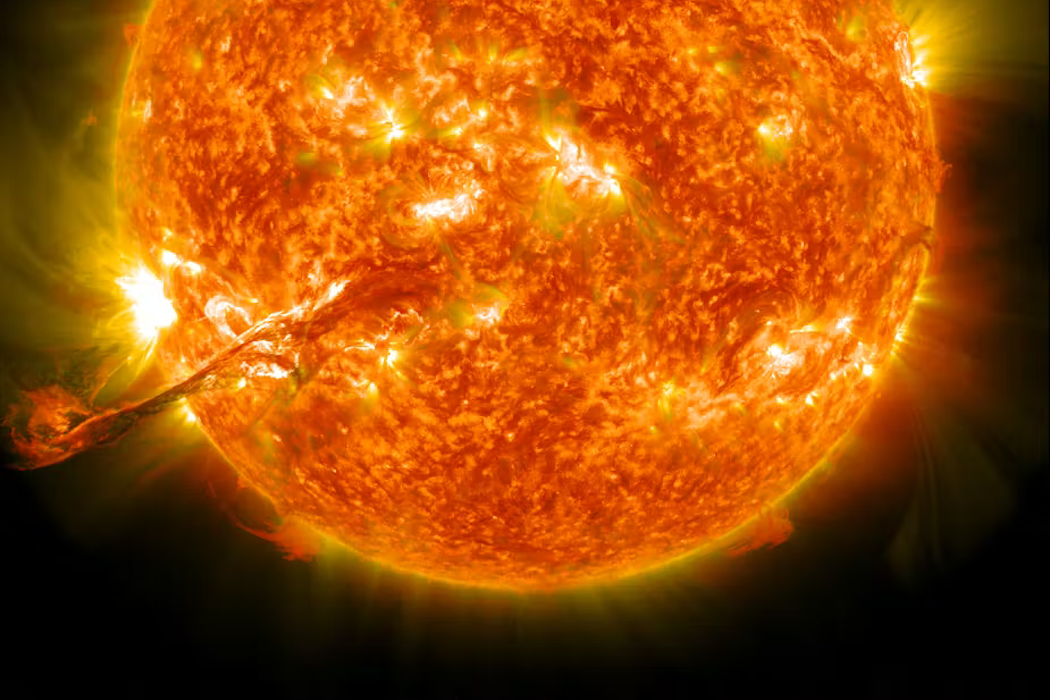

The most famous controversy, perhaps, dealt with contraception. In the early 2000s, some pharmacists refused to dispense Plan B, also known as “emergency contraception” or the “morning-after pill.” Their refusal stemmed from a belief that it caused an abortion.

That is inaccurate, according to medical authorities. When Plan B first became available in 1999, the label said the medication might work by expelling an egg that had already been fertilized. In 2022, the Food and Drug Administration relabeled Plan B to say that it acts before fertilization. From a medical perspective, both mechanisms are contraception, not abortion.

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

States responded to pharmacists’ refusals by adopting “responsibility laws.” Some states adopted “conscience clauses” that permitted pharmacists not to fill the prescription. Others opted for “duty to dispense” laws that required pharmacists or pharmacies to provide the medication, or “refuse and refer” laws obligating objecting pharmacists to hand the prescription off to a colleague.

This fight largely broke down across political lines. Groups that oppose abortion rights argued that pharmacists should have the right to opt out, while groups in favor of abortion rights argued that pharmacists should be required to dispense.

As this fight escalated, the conflict became about more than contraception or abortion. It revealed Americans’ views about what kinds of professionals pharmacists should be, and whether they are professionals at all – that is, members of occupational groups that have specialized knowledge and skills, and exclusive rights to do particular kinds of work.

In 2015, for example, the advocacy group NARAL Pro-Choice American – now called Reproductive Freedom for All – released an ad with a man and a woman in bed, their feet hanging out of the sheets. Stuck between them was someone else wearing heavy black shoes. “Who invited the pharmacist?” the ad asked.

Pro-choice organizations insisted that pharmacists had no right to question a doctor’s prescription. “A pharmacist’s job is to dispense medication, not moral judgment,” said the president of Planned Parenthood Chicago.

Some pharmacists felt that such messages did not just criticize “moral gatekeeping” but also undermined their claims to professional authority. Pharmacists undergo six years of training to earn a doctorate and are health care’s medication specialists. The idea that pharmacists were simply technicians, hired to fill whatever a prescription said, made them seem like physicians’ underlings.

Keeping patients safe

A short time later, when the opioid overdose crisis began to escalate, pharmacists again found themselves pulled in two directions. This time, the question was whether they should be both medical and legal gatekeepers.

When the U.S. first tried to crack down on unauthorized opioid use, many pharmacists felt ambivalent about tasks like identifying people who were misusing or selling medications. One pharmacist told me, “Although I’m in the business of patient safety, I’m not in the police business.”

Later, pharmacists began to see policing tasks as health care tasks. They reasoned that policing patients helped keep patients safe, and they embraced enforcement as a key component of their work.

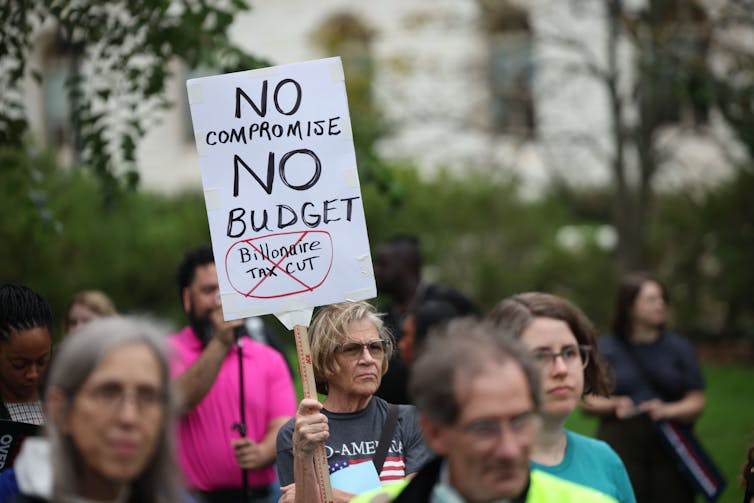

Fast-forward to 2021. America was in the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic, and some doctors were prescribing hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin to treat sick patients, though the FDA had not approved the medications for that purpose. Many pharmacists refused to fill those prescriptions, citing lack of scientific evidence and potential harm.

AP Photo/Ted S. Warren

Legislators in Missouri, where I teach, responded by passing a bill that required pharmacists to dispense the two medications, no questions asked – though that rule was later struck down by a federal judge. Similar conflicts played out in Iowa and Ohio, among other states.

Again, the fight broke down along political lines, but in the opposite direction. Liberals tended to oppose the bills, portraying pharmacists as skilled professionals whose expertise is essential to prevent harm. Conservative supporters claimed that pharmacists should dispense whatever the doctor writes.

Professional power

Each of these controversies has focused on a specific legal, ethical or medical issue. By extension, though, they are also about what kinds of professional discretion pharmacists should be able to exercise.

When it comes to medication, doctors prescribe, nurses administer and pharmacists dispense. Before the 20th century, pharmacists diagnosed disease and also compounded drugs. That changed when physicians placed themselves at the top of the medical hierarchy.

When it comes to professional autonomy, states regulate health care, but they permit health care professions to regulate themselves: to educate, license and discipline their own workers through professional boards. In exchange, these boards must do so “in the public interest” – prioritizing public health, safety and welfare over professionals’ own interests.

Health care professionals, including pharmacists, must also follow ethical codes. The day they receive their iconic white coats, pharmacists vow to “consider the welfare of humanity and relief of suffering [their] primary concerns.” Pharmacists also commit to “respecting the autonomy and dignity of each patient,” which means that pharmacists partner with patients to make choices about their health.

Self-regulation has legally given pharmacists the right to act as “medical gatekeepers” – to use their professional expertise to keep patients safe. This role is critical, as patients whose lives have been saved by pharmacists catching errors can attest.

It has not, however, given them the right to be “moral gatekeepers” who put their personal beliefs above the patient’s. Pharmacists control medications because of professional commitments, not personal beliefs. The code of ethics describes the pharmacist-patient relationship as a “covenant” that creates moral obligations for the pharmacist – including helping “individuals achieve optimum benefit from their medications,” being “committed to their welfare” and maintaining their trust.

If pharmacists wish to regulate themselves, history makes clear they need to define what it means to act in the public interest and ensure that other pharmacists comply. If not, the state has proved more than willing to step in and do the job for them. They may not like the results.

![]()

Elizabeth Chiarello has received funding from the National Science Foundation.

– ref. Conflict at the counter: When pharmacists’ and patients’ values collide – https://theconversation.com/conflict-at-the-counter-when-pharmacists-and-patients-values-collide-264844