Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Aaron Mansfield, Assistant Professor of Sport Management, Merrimack College

Being from Buffalo means getting to eat some of the best wings in the world. It means scraping snow and ice off your car in frigid mornings. And it means making a lifelong vow to the city’s NFL franchise, the Bills – for better or worse, till death do us part.

When I grew up in New York’s second-largest city, my community was bound together by loyalty to a football team that always found new ways to break our hearts. And yet at the start of each NFL season, we always found reasons to hope – we couldn’t help ourselves.

Coming from this football-crazed culture, I often wondered about the psychology of fandom. This eventually led me to pursue a Ph.D. in sport consumer behavior. As a doctoral student, I was most interested in one question: Is fandom good for us?

I found a huge body of research on the psychological and social effects of fandom, and it certainly made being devoted to a team look good. Fandom builds belonging, helps adults make friends, boosts happiness and even provides a buffer against traumatic life events.

So, fandom is great, right?

As famed football commentator Lee Corso would say: “Not so fast, my friend.”

While fandom appears to be a boon for our mental health, strikingly little research had been conducted on the relationship between fandom and physical health.

So I decided to conduct a series of studies – mainly of people in Western countries – on this topic. I found that being a sports fan can have some drawbacks for physical health, especially among the most committed fans.

Reach for the nachos

Playing sports is healthy. But watching them? Not so much.

Tailgating culture revolves around alcohol. Research shows that college sports fans binge drink at significantly higher rates than nonfans, are more likely to do something they later regretted and are more likely to drive drunk. Meanwhile, watch parties encourage being stationary for hours and mindlessly snacking. And, of course, fandom goes hand in hand with heavily processed foods like wings, nachos, pizza and hot dogs.

One fan told me that when watching games, his relationship with food is “almost Pavlovian”; he craves “decadent” foods the same way he seeks out popcorn at the movies.

George Rose/Getty Images

Inside the stadium, healthy options have traditionally been scarce and overpriced. A Sports Illustrated writer joked in 1966 that fans leave stadiums and arenas with “the same body chemistry as a jelly doughnut.”

Little seems to have changed since. One Gen Z fan I recently interviewed griped, “You might find one salad with a plain piece of lettuce and a quarter of a tomato.”

Eating away the anxiety and pain

The relationship between fandom and physical health isn’t just about guzzling beer, sitting for hours on end or scarfing down hot dogs.

One study analyzed sales from grocery stores. The researchers found that fans consume more calories – and less healthy food – on the day following a loss by their favorite team, a reaction the researchers tied to stress and disappointment.

My colleagues and I found something similar: Fandom induces what’s called “emotional eating.”

Emotions like anger, sadness and disappointment lead to stronger cravings. And this relationship is tied to how your favorite team performs when it matters most. For example, we found that games between rivals and closely contested games yield more pronounced effects. Emotional states generated by the game are also significantly correlated with increased beer sales in the stadium.

High-calorie cultures

In another paper, my co-authors and I found that fans often feel torn between their desire to make healthy choices and their commitment to being a “true fan.”

Every fan base develops its own culture. These unwritten rules vary from team to team, and they aren’t just about wearing a cheesehead hat or waving a Terrible Towel. They also include expectations around drinking, eating and lifestyle.

These health-related norms are shaped by a variety of factors, including the region’s culture, team history and even team sponsorships.

For example, the Cincinnati Bengals partner with Skyline Chili, a regional chain that makes a meat sauce that’s often poured over hot dogs or spaghetti. One Bengals fan I interviewed observed that if you attend a Bengals game, sure, you could eat something else – but a “true fan” eats Skyline.

I have two studies in progress that show how hardcore fans typically align their health behaviors with the health norms of their fan base. This becomes a way to signal their allegiance to the team, improve their standing among fellow fans, and contribute to what makes the fan base distinct in the eyes of its members.

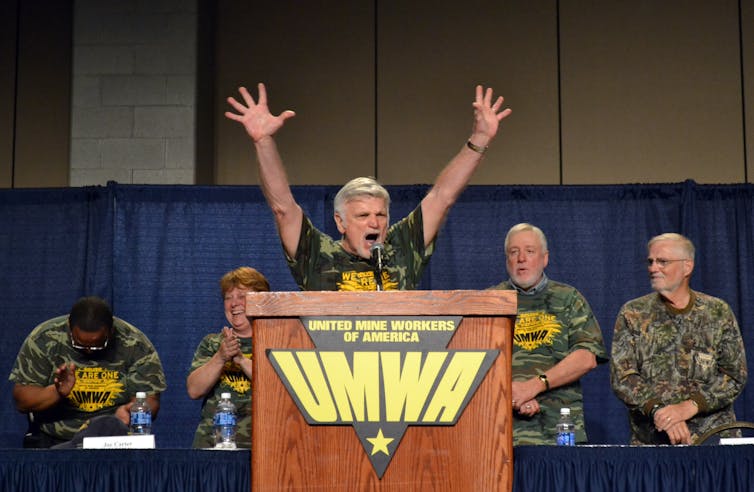

Jeff Haynes/AFP via Getty Images

In Buffalo, for example, tailgating often revolves around alcohol – so much so that Bills fans have a reputation for over-the-top drinking rituals.

And in New Orleans, Saints fans often link fandom to Louisiana food traditions. As one fan explained: “People make a bunch of fried food or huge pots of gumbo or étouffée, and eat all day – from hours before the game until hours after.”

A new generation of health-conscious fans

The fan experience is shaped by the culture in which it is embedded. Teams actively help shape these cultures, and there’s a business argument to be had for teams to play a bigger role in changing some of these norms.

Gen Z is strikingly health-conscious. They’re also less engaged with traditional fandom.

If stadiums and tailgates continue to revolve around beer and nachos, why would a generation attuned to fitness influencers and “fitspiration” buy in? To reach this market, I think the sports industry will need to promote its professional sports teams in new ways.

Some teams are already doing so. The British soccer team Liverpool has partnered with the exercise equipment company Peloton. Another club, Manchester City, has teamed up with a nonalcoholic beer brand as the official sponsor of its practice uniforms.

And several European soccer clubs have even joined a “Healthy Stadia” movement, revamping in-stadium food options and encouraging fans to walk and bike to the stadium.

For the record, I don’t think the solution is replacing typical fan foods with smoothies and salads. Alienating core consumers is generally not a sound business strategy.

I think it’s reasonable, however, to suggest sports teams might add more healthy options and carefully evaluate the signals they send through sponsorships.

As one fan I recently interviewed said: “The NFL has had half-assed efforts like Play 60” – a campaign encouraging kids to get at least 60 minutes of physical activity per day – “while also making a ton of money from beer, food and, back in the day, cigarette advertisements. How can sports leagues seriously expect people to be healthier if they promote unhealthy behaviors?”

Today’s consumers want to support brands that reflect their values. This is particularly true for Gen Zers, many of whom are savvy enough to see through hollow campaigns and quick to reject hypocrisy. In the long run, I think this type of dissonance – sandwiching a Play 60 commercial between ads for Uber Eats and Anheuser-Busch – will prove counterproductive.

Scott Winters/Icon Sportswire via Getty Images

I, as much as anyone else, understand what makes fandom special – and yes, I’ve eaten my share of wings during Bills games. But public health is a pressing concern, and though the sports industry is well-positioned to address this issue, fandom isn’t helping. Actually, my research suggests it’s having the opposite effect.

Striking the balance I’m advocating will be tricky, but the sports industry is filled with bright problem-solvers. In the film “Moneyball,” Brad Pitt’s character, Billy Beane, famously says sports teams must “adapt or die.” He was referring to the need for baseball teams to integrate analytics into their decision-making.

Professional sports teams eventually got that message. Maybe they’ll get this one, too.

![]()

Aaron Mansfield does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Wings, booze and heartbreak – what my research says about the hidden costs of sports fandom – https://theconversation.com/wings-booze-and-heartbreak-what-my-research-says-about-the-hidden-costs-of-sports-fandom-265158