Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Neal H. Hutchens, University Research Professor of Education, University of Kentucky

American colleges and universities are increasingly firing or punishing professors and other employees for what they say, whether it’s on social media or in the classroom.

After the Sept. 10, 2025, killing of conservative activist Charlie Kirk, several universities, including Iowa State University, Clemson University, Ball State University and others, fired or suspended employees for making negative online comments about Kirk.

Some of these dismissed professors compared Kirk to a Nazi, described his views as hateful, or said there was no reason to be sorry about his death.

Some professors are now suing their employers for taking disciplinary action against them, claiming they are violating their First Amendment rights.

In one case, the University of South Dakota fired Phillip Michael Cook, a tenured art professor, after he posted on Facebook in September that Kirk was a “hate spreading Nazi.” Cook, who took down his post within a few hours and apologized for it, then sued the school, saying it was violating his First Amendment rights.

A federal judge stated in a Sept. 23 preliminary order that the First Amendment likely protected what Cook posted. The judge ordered the University of South Dakota to reinstate Cook, and the university announced on Oct. 4 that it would reverse Cook’s firing.

Cook’s lawsuit, as well as other lawsuits filed by dismissed professors, is testing how much legal authority colleges have over their employees’ speech – both when they are on the job and when they are not.

For decades, American colleges and universities have traditionally encouraged free speech and open debate as a core part of their academic mission.

As scholars who study college free speech and academic freedom, we recognize that these events raise an important question: When, if ever, can a college legally discipline an employee for what they say?

anup khanal – CC BY-SA 4.0

Limits of public employees’ speech rights

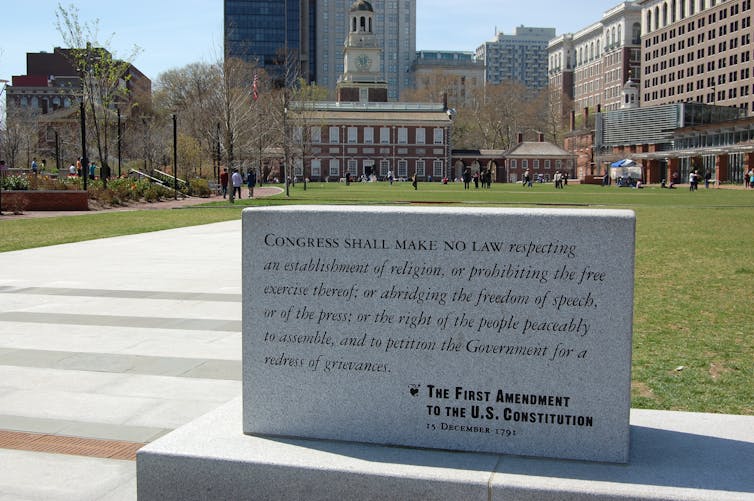

The First Amendment limits the government’s power to censor people’s free speech. People in the United States can, for instance, join protests, criticize the government and say things that others find offensive.

But the First Amendment only applies to the government – which includes public colleges and universities – and not private institutions or companies, including private colleges and universities.

This means private colleges typically have wide authority to discipline employees for their speech.

In contrast, public colleges are considered part of the government. The First Amendment limits the legal authority they have over their employees’ speech. This is especially true when an employee is speaking as a private citizen – such as participating in a political rally outside of work hours, for example.

The Supreme Court ruled in a landmark 1968 case that public employees’ speech rights as private citizens can extend to criticizing their employer, like if they write a letter critical of their employer to a newspaper.

The Supreme Court also ruled in 2006 that

the First Amendment does not protect public employees from being disciplined by their employers when they say or write something as part of their official job duties.

Even when a public college employee is speaking outside of their job duties as a private citizen, they might not be guaranteed First Amendment protection. To reach this legal threshold, what they say must be about something of importance to the public, or what courts call a “matter of public concern.”

Talking or writing about news, politics or social matters – Kirk’s murder – often meets the legal test for when speech is about a matter of public concern.

In contrast, courts have ruled that personal workplace complaints or gossip typically does not guarantee freedom of speech protection.

And in some cases, even when a public employee speaks as a private citizen on a topic that a court considers a matter of public concern, their speech may still be unprotected.

A public employer can still convince a court that its reasons for prohibiting an employee’s speech – like preventing conflict among co-workers – are important enough to deny this employee First Amendment protection.

Lawsuits brought by the employees of public colleges and universities who have been fired for their comments about Kirk may likely be decided based on whether what they said or wrote amounts to a matter of public concern. Another important factor is whether a court is convinced that an employee’s speech about Kirk was serious enough to disrupt a college’s operations, thus justifying the employee’s firing.

Academic freedom and professors’ speech

There are also questions over whether professors at public universities, in particular, can cite other legal rights to protect their speech.

Academic freedom refers to a faculty member’s rights connected to their teaching and research expertise.

At both private and public colleges, professors’ work contracts – like the ones typically signed after receiving tenure – potentially provide legal protections for faculty speech connected to academic freedom, such as in the classroom.

However, the First Amendment does not apply to how a private college regulates its professors’ speech or academic freedom.

Professors at public colleges have at least the same First Amendment free speech rights as their fellow employees, like when speaking in a private citizen capacity.

Additionally, the First Amendment might protect a public college professor’s work-related speech when academic freedom concerns arise, like in their teaching and research.

In 2006, the Supreme Court left open the question of whether the First Amendment covers academic freedom, in a case where it found the First Amendment did not cover what public employees say when carrying out their official work.

Since then, the Supreme Court has not dealt with this complicated issue. And lower federal courts have reached conflicting decisions about First Amendment protection for public college professors’ speech in their teaching and research.

StephanieCraig/iStock via Getty Images Plus

Future of free speech for university employees

Some colleges, especially public ones, are testing the legal limits of their authority over their employees’ speech.

These incidents demonstrate a culture of extreme political polarization in higher education.

Beyond legal questions, colleges are also grappling with how to define their commitments to free speech and academic freedom.

In particular, we believe campus leaders should consider the purpose of higher education. Even if legally permitted, restricting employees’ speech could run counter to colleges’ traditional role as places for the open exchange of ideas.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Does the First Amendment protect professors being fired over what they say? It depends – https://theconversation.com/does-the-first-amendment-protect-professors-being-fired-over-what-they-say-it-depends-266128