Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Ediberto Román, Professor of Law, Florida International University

Soon after the NFL’s announcement that Puerto Rican rapper Bad Bunny would headline the Super Bowl halftime show, conservative media outlets and Trump administration officials went on the attack.

Homeland Security head Kristi Noem promised that U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement “would be all over the Super Bowl.” President Donald Trump called the selection “absolutely ridiculous.” Right-wing commentator Benny Johnson bemoaned the fact that the rapper has “no songs in English.” Bad Bunny, conservative pundit Tomi Lahren complained, is “Not an American artist.”

Bad Bunny – born Benito A. Martínez Ocasio – is a superstar, one of the top-streaming artists in the world. And because he is Puerto Rican, he’s a U.S. citizen, too.

To be sure, Bad Bunny checks many boxes that irk conservatives. He endorsed Kamala Harris for president in 2024. There’s his gender-bending wardrobe. He has slammed the Trump administration’s anti-immigration policies. He has declined to tour on the U.S. mainland, fearing that some of his fans could be targeted and deported by ICE. And his explicit lyrics – most of which are in Spanish – would make even the most ardent free speech warrior cringe.

And yet, as experts on issues of national identity and U.S. immigration policies, we think Lahren’s and Johnson’s insults get at the heart of why the rapper has created such a firestorm on the right. The spectacle of a Spanish-speaking rapper performing during the most-watched sporting event on American TV is a direct rebuke of the Trump administration’s efforts to paper over the country’s diversity.

The Puerto Rican colony

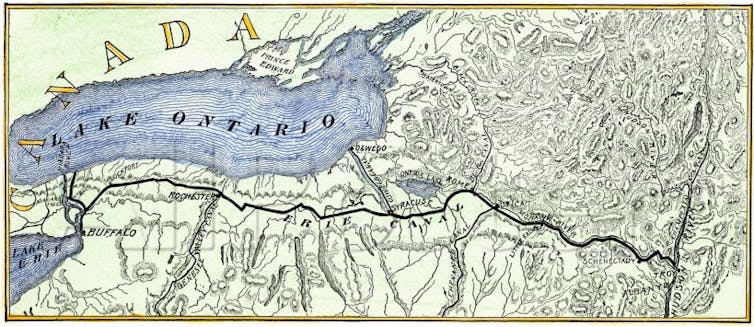

Bad Bunny was born in 1994 in Puerto Rico, an unincorporated U.S. territory that the country acquired after the 1898 Spanish-American War.

It is home to 3.2 million U.S. citizens by birth. If it were a state, it would be the 30th largest by population, according to the 2020 U.S. Census.

But Puerto Rico is not a state; it is a colony from a bygone era of U.S. overseas imperial expansion. Puerto Ricans do not have voting representatives in Congress, and they do not get to help elect the president of the United States. They are also divided over the island’s future. Large pluralities seek either U.S. statehood or an enhanced form of the current commonwealth status, while a smaller minority vie for independence.

Mario Tama/Getty Images

But one thing is clear to all Puerto Ricans: They’re from a nonsovereign land, with a clearly defined Latin American culture – one of the oldest in the Americas. Puerto Rico may belong to the U.S. – and many Puerto Ricans embrace that special relationship – but the island itself does not sound or feel like the U.S.

The over 5.8 million Puerto Ricans that reside in the 50 states further complicate that picture. While legally they are U.S. citizens, mainstream Americans often don’t see Puerto Ricans that way. In fact, a 2017 poll found that only 54% of Americans knew that Puerto Ricans were U.S. citizens.

The alien-citizen paradox

Puerto Ricans exist in what we describe as the “alien-citizen paradox”: They are U.S. citizens, but only those residing in the mainland enjoy all the rights of citizenship.

A recent congressional report stated that U.S. citizenship for Puerto Ricans “is not equal, permanent, irrevocable citizenship protected by the 14th Amendment … and Congress retains the right to determine the disposition of the territory.” Any U.S. citizen that moves to Puerto Rico no longer possesses the full rights of U.S. citizens of the mainland.

Bad Bunny’s selection for the Super Bowl halftime show illustrates this paradox. In addition to criticisms from public figures, there were widespread calls among MAGA influencers to deport the rapper

This is but one way Puerto Ricans, as well as other Latino citizens, are reminded of their status as “others.”

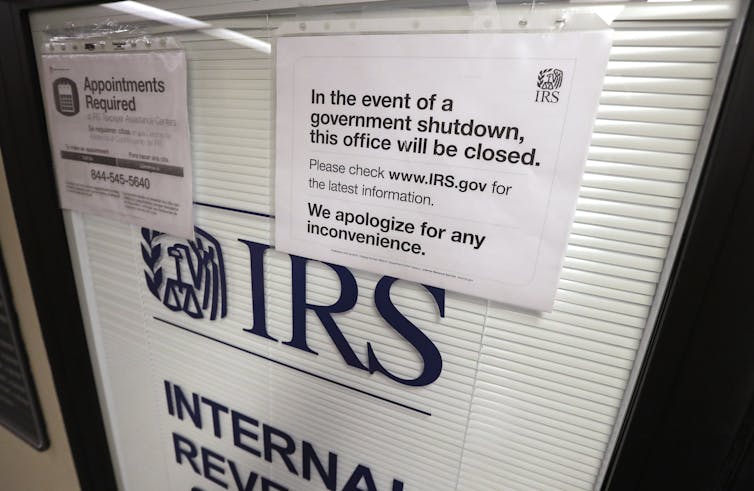

ICE apprehensions of people merely appearing to be an immigrant – a tactic that was recently given the blessing of the Supreme Court – is an example of their alienlike status.

And the bulk of the ICE raids have occurred in predominantly Latino communities in Los Angeles, Chicago and New York. This has forced many Latino communities to cancel Hispanic Heritage Month celebrations.

Bad Bunny’s global reach

The xenophobic fervor against Bad Bunny has led political leaders like House Speaker Mike Johnson to call for a more suitable figure for the Super Bowl, such as country music artist Lee Greenwood. Referring to Bad Bunny, Johnson said “it sounds like he’s not someone who appeals to a broader audience.”

But the facts counter that claim. The Puerto Rican artist sits atop the global music charts. He has over 80 million monthly Spotify listeners. And he has sold nearly five times more albums than Greenwood.

That global appeal has impressed the NFL, which hopes to host as many as eight international games next season. Additionally, Latinos represent the league’s fastest-growing fan base, and Mexico is its largest international market, with a reported 39.5 million fans.

The Bad Bunny Super Bowl saga may actually become an important political moment. Conservatives, in their efforts to highlight Bad Bunny’s “otherness” – despite the United States being the second-largest Spanish-speaking country in the world – may have unwittingly educated America on the U.S. citizenship of Puerto Ricans.

In the meantime, Puerto Ricans and the rest of the U.S. Latino community continue to wonder when they’ll be accepted as social equals.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. The real reason conservatives are furious about Bad Bunny’s forthcoming Super Bowl performance – https://theconversation.com/the-real-reason-conservatives-are-furious-about-bad-bunnys-forthcoming-super-bowl-performance-267078