Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Navid Tahvildari, Associate Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Florida International University

Hurricanes are America’s most destructive natural hazards, causing more deaths and property damage than any other type of disaster. Since 1980, these powerful tropical storms have done more than US$1.5 trillion in damage and killed more than 7,000 people.

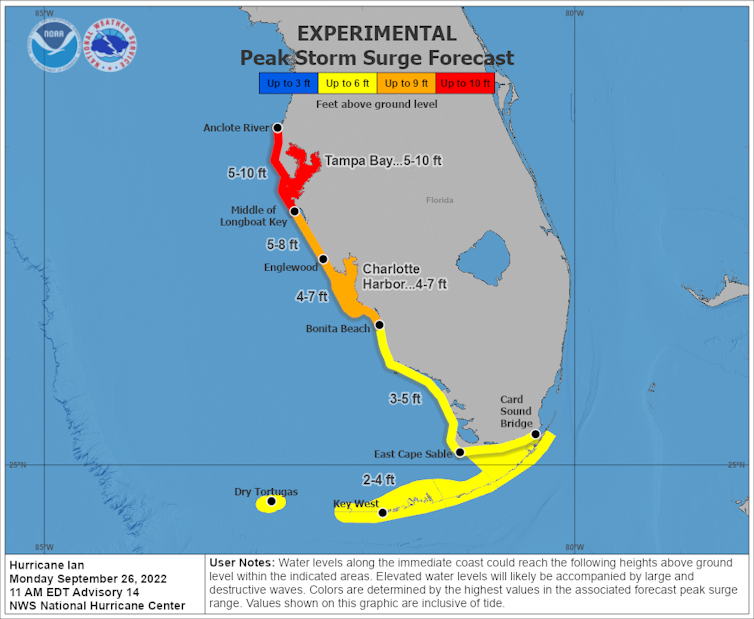

The No. 1 cause of the damages and deaths from hurricanes is storm surge.

Storm surge is the rise in the ocean’s water level, caused by a combination of powerful winds pushing water toward the coastline and reduced air pressure within the hurricane compared to the pressure outside of it. In addition to these factors, waves breaking close to the coast causes sea level to increase near the coastline, a phenomenon we call wave setup, which can be an important component of storm surge.

Accurate storm surge predictions are critical for giving coastal residents time to evacuate and giving emergency responders time to prepare. But storm surge forecasts at high resolution can be slow.

Ricardo Arduengo/AFP via Getty Images

As a coastal engineer, I study how storm surge and waves interact with natural and human-made features on the ocean floor and coast and ways to mitigate their impact. I have used physics-based models for coastal flooding and have recently been exploring ways that artificial intelligence can improve the speed of storm surge forecasting.

How storm surge is forecast today

Today, operational storm surge forecasts rely on hydrodynamic models, which are based on the physics of water flow.

These models use current environmental conditions – such as how fast the storm is moving toward shore, its wind speed and direction, the timing of the tide, and the shape of the seafloor and the landscape – to compute the projected surge height and determine which locations are most at risk.

Hydrodynamic models have substantially improved in recent decades, and computers have become significantly more powerful, such that rapid low-resolution simulations are possible over very large areas. However, high-resolution simulation that provide neighborhood-level detail can take several hours to run.

Those hours can be critical for communities at risk to evacuate safely and for emergency responders to prepare adequately.

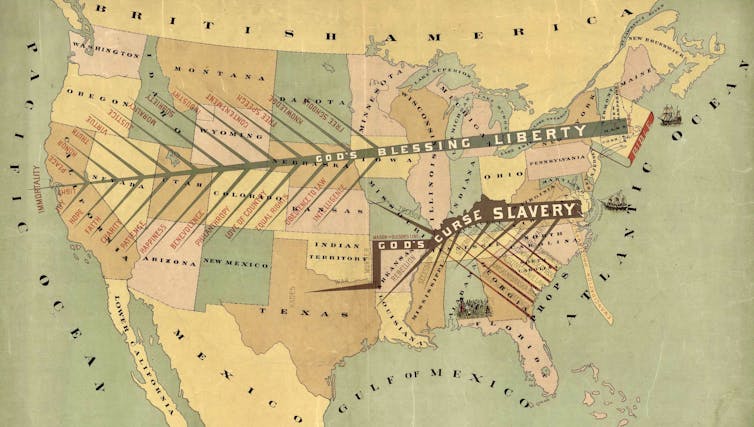

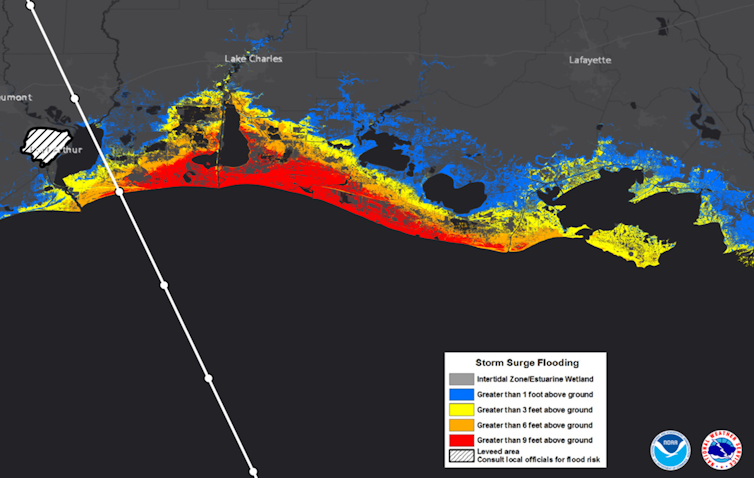

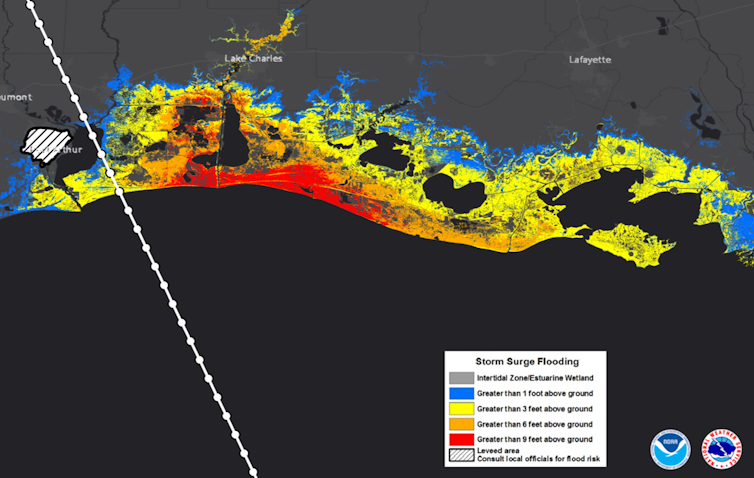

NOAA

To forecast storm surge across a wide area, modelers break up the target area into many small pieces that together form a computational grid or mesh. Picture pixels in an image. The smaller the grid pieces, or cells, the higher the resolution and the more accurate the forecast. However, creating many small cells across a large area requires greater computing power, so forecasting storm surge takes longer as a result.

Forecasters can use low-resolution computer grids to speed up the process, but that reduces accuracy, leaving communities with more uncertainty about their flood risk.

AI can help speed that up.

How AI can create better forecasts

There are two main sources of uncertainty in storm surge predictions.

One involves the data fed into the computer model. A hurricane’s storm track and wind field, which determine where it will make landfall and how intense the surge will be, are still hard to forecast accurately more than a few days in advance. Changes to the coast and sea floor, such as from channel dredging or loss of salt marshes, mangroves or sand dunes, can affect the resistance that storm surge will face.

The second uncertainty involves the resolution of the computational grid, over which the mathematical equations of the surge and wave motion are solved. The resolution determines how well the model sees changes in landscape elevation and land cover and accounts for them, and at how much granularity the physics of hurricane surge and waves is solved.

NOAA

NOAA

AI models can produce detailed predictions faster. For example, engineers and scientists have developed AI models based on deep neural networks that can predict water levels along the coastline quickly and accurately by using data about the wind field. In some cases, these models have been more accurate than traditional hydrodynamic models.

AI can also develop forecasts for areas with little historic data, or be used to understand extreme conditions that may not have occurred there before.

For these forecasts, physics-based models can be used to generate synthetic data to train the AI on scenarios that might be possible but haven’t actually happened. Once an AI model is trained on both the historic and synthetic data, it can quickly generate surge forecasts using details about the wind and atmospheric pressure.

Training the AI on data from hydrodynamic models can also improve its ability to quickly generate inundation risk maps showing which streets or houses are likely to flood in extreme events that may not have a historical precedent but could happen in the future.

The future of AI for hurricane forecasting

AI is already being used in operational storm surge forecasts in a limited way, mainly to augment the commonly used physics-based models.

In addition to improving those methods, my team and other researchers have been developing ways to use AI for storm surge prediction using observed data, assessing the damage after hurricanes and processing camera images to deduce flood intensity. That can fill a critical gap in the data needed for validating storm surge models at granular levels.

As artificial intelligence models rapidly spread through every aspect of our lives and more data becomes available for training them, the technology offers potential to improve hurricane and storm surge forecasting in the future, giving coastal communities faster and more detailed warnings about the risks on the way.

![]()

Navid Tahvildari’s research on coastal flooding has been funded by NSF, NOAA, NASA, and DOT.

– ref. How AI can improve storm surge forecasts to help save lives – https://theconversation.com/how-ai-can-improve-storm-surge-forecasts-to-help-save-lives-259007