Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Jared Bahir Browsh, Assistant Teaching Professor of Critical Sports Studies, University of Colorado Boulder

Donald Trump, it is fair to assume, will be switching channels during this year’s Super Bowl halftime show.

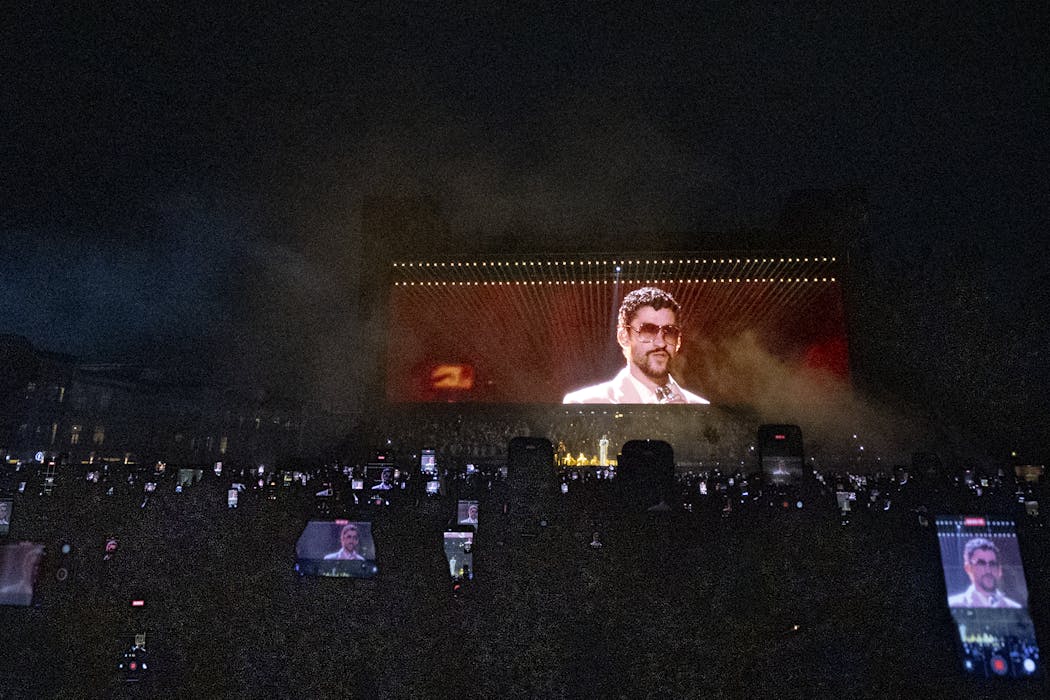

The U.S. president has already said that he won’t be attending Super Bowl LX in person, suggesting that the venue, Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, California, was “just too far away.” But the choice of celebrity entertainment planned for the main break – Puerto Rican reggaeton star Bad Bunny and recently announced pregame addition Green Day – didn’t appeal. “I’m anti-them. I think it’s a terrible choice. All it does is sow hatred. Terrible,” Trump told the New York Post.

National Football League Commissioner Roger Goodell likely didn’t have the sensibilities of the U.S. president in mind when the choice of Bad Bunny was made.

One of the top artists in the world, Bad Bunny performs primarily in Spanish and has been critical of immigration enforcement, which factored into the backlash in some conservative circles to the choice. Bad Bunny’s anti-ICE comments at this year’s Grammy Awards will have only stoked the ire of some conservatives.

But for the NFL hierarchy, this was likely a business decision, not a political one. The league has its eyes on expansion into Latin America; Bad Bunny, they hope, will be a ratings-winning means to an end. It has made such bets in the past. In 2020, Shakira and Jennifer Lopez were chosen to perform, with Bad Bunny making an appearance. The choice then, too, was seen as controversial.

Al Bello/Getty Images

Raising the flag overseas

As a teacher and scholar of critical sports studies, I study the global growth of U.S.-based sports leagues overseas.

Some, like the National Basketball Association, are at an advantage. The sport is played around the globe and has large support bases in Asia – notably in the Philippines and China – as well as in Europe, Australia and Canada.

The NFL, by contrast, is largely entering markets that have comparatively little knowledge and experience with football and its players.

The league has opted for a multiprong approach to attracting international fans, including lobbying to get flag football into the 2028 Olympics in Los Angeles.

Playing the field

When it comes to the traditional tackle game, the NFL has held global aspirations for over three-quarters of a century. Between 1950-1961, before they merged, the NFL and American Football League played seven games against teams in Canada’s CFL to strengthen the relationship between the two nations’ leagues.

Developing a fan base south of the border has long been part of the plan.

The first international exhibition game between two NFL teams was supposed to take place in Mexico City in 1968. But Mexican protest over the economy and cost of staging the Olympics that year led the game, between the Detroit Lions and Philadelphia Eagles, to be canceled.

Instead, it was Montreal that staged the first international exhibition match the following year.

In 1986, the NFL added an annual international preseason game, the “American Bowl,” to reach international fans, including several games in Mexico City and one in Monterrey.

But the more concerted effort was to grow football in the potentially lucrative, and familiar, European market.

After several attempts by the NFL and other entities in the 1970s and ’80s to establish an international football league, the NFL-backed World League of Football launched in 1991. Featuring six teams from the United States, one from Canada and three from Europe, the spring league lost money but provided evidence that there was a market for American football in Europe, leading to the establishment of NFL Europe.

But NFL bosses have long had wider ambitions. The league staged 13 games in Tokyo, beginning in 1976, and planned exhibitions for 2007 and 2009 in China that were ultimately canceled. These attempts did not have the same success as in Europe.

Beyond exhibitions

The NFL’s outreach in Latin America has been decades in the making. After six exhibition matches in Mexico between 1978 and 2001, the NFL chose Mexico City as the venue of its first regular season game outside the United States.

In 2005, it pitted the Arizona Cardinals against the San Francisco 49ers at Estadio Azteca in Mexico City. Marketed as “Fútbol Americano,” it drew the largest attendance in NFL history, with over 103,000 spectators.

The following year, Goodell was named commissioner and announced that the NFL would focus future international efforts on regular-season games.

The U.K. was a safe bet due to the established stadium infrastructure and the country’s small but passionate fan base. The NFL International Series was played exclusively in London between 2007 and 2016.

But in 2016, the NFL finally returned to Mexico City, staging a regular-season game between the Oakland – now Las Vegas – Raiders and Houston Texans.

And after the completion of upgrades to Latin America’s largest stadium, Estadio Azteca, the NFL will return to Mexico City in 2026, along with games in Munich, Berlin and London. Future plans include expanding the series to include Sydney, Australia, and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 2026.

The International Player Pathway program also offers players from outside the United States an opportunity to train and earn a roster spot on an NFL team. The hope is that future Latin American players could help expand the sport in their home countries, similar to how Yao Ming expanded the NBA fan base in China after joining the Houston Rockets, and Shohei Ohtani did the same for baseball in Japan while playing in Los Angeles.

Heading south of the border

The NFL’s strategy has gained the league a foothold in Latin America.

Mexico and Brazil have become the two largest international markets for the NFL, with nearly 40 million fans in each of the nations.

Although this represents a fraction of the overall sports fans in each nation, the raw numbers match the overall Latino fan base in the United States. In recent years the NFL has celebrated Latino Heritage Month through its Por La Cultura campaign, highlighting Latino players past and present.

Latin America also offers practical advantages. Mexico has long had access to NFL games as the southern neighbor to the United States, with the Dallas Cowboys among the most popular teams in Mexico.

For broadcasters, Central and South America offer less disruption in regards to time zones. Games in Europe start as early as 6:30 a.m. for West Coast fans, whereas Mexico City follows Central time, and Brasilia time is only one to two hours ahead of Eastern time.

Matt Winkelmeyer/Getty Images for The Recording Academy

The NFL’s expansion plans are not without criticism. Domestically, fans have complained that teams playing outside the U.S. borders means one less home game for season-ticket holders. And some teams have embraced international games more than others.

Another criticism is the league, which has reported revenues of over US$23 billion during the 2024-25 season – nearly double any other U.S.-based league – is using its resources to displace local sports. There are also those who see expansion of the league as a form of cultural imperialism. These criticisms often intersect with long-held ideas around the league promoting militarism, nationalism and American exceptionalism.

Bad Bunny: No Hail Mary attempt

For sure, the choice of Bad Bunny as the halftime pick is controversial, given the current political climate around immigration. The artist removed tour dates on the U.S. mainland in 2025 due to concerns about ICE targeting fans at his concerts, a concern reinforced by threats from the Department of Homeland Security that they would do just that at the Super Bowl.

But in sticking with Bad Bunny, the NFL is showing it is willing to face down a section of its traditional support and bet instead on Latin American fans not just tuning in for the halftime show but for the whole game – and falling in love with football, too.

![]()

Jared Bahir Browsh does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl show is part of long play drawn up by NFL to score with Latin America – https://theconversation.com/bad-bunnys-super-bowl-show-is-part-of-long-play-drawn-up-by-nfl-to-score-with-latin-america-271068