Source: The Conversation – USA – By Steven Lamy, Professor Emeritus of Political Science and International Relations and Spatial Sciences, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

In 2019, during his first term, U.S. President Donald Trump expressed a desire to buy Greenland, which has been a part of Denmark for some 300 years. Danes and Greenlanders quickly rebuffed the offer at the time.

During Trump’s second term, those offers have turned to threats.

Trump said on his social media platform Truth Social in late December 2024 that, for purposes of national security, U.S. control over Greenland was a necessity. The president has continued to insist on the national security rationale into January 2026. And he has refused to rule out the use of military force to control Greenland.

From my perspective as an international relations scholar focused on Europe, Trump’s national security rationale doesn’t make sense. Greenland, like the U.S., is a member of NATO, which provides a collective defense pact, meaning member nations will respond to an attack on any alliance member. And because of a 1951 defense agreement between the U.S. and Denmark, the U.S. can already build military installations in Greenland to protect the region.

Trump’s 2025 National Security Strategy, which stresses control of the Western Hemisphere and keeping China out of the region, provides insight into Trump’s thinking.

US interests in Greenland

The United States has tried to acquire Greenland several times.

In 1867, Secretary of State William Seward commissioned a survey of Greenland. Impressed with the abundance of natural resources on the island, he pushed to acquire Greenland and Iceland for US$5.5 million – roughly $125 million today.

But Congress was still concerned about the purchase of Alaska that year, which Seward had engineered. It had seen Alaska as too cold and too distant from the rest of the U.S. to justify spending $7.2 million – roughly $164 million today – although Congress ultimately agreed to do it. There was not enough national support for another frozen land.

In 1910, the U.S. ambassador to Denmark proposed a complex trade involving Germany, Denmark and the United States. Denmark would give the U.S. Greenland, and the U.S. would give Denmark islands in the Philippines. Denmark would then give those islands to Germany, and Germany would return Schleswig-Holstein – Germany’s northernmost state – to Denmark.

But the U.S. quickly dismissed the proposed trade as too audacious.

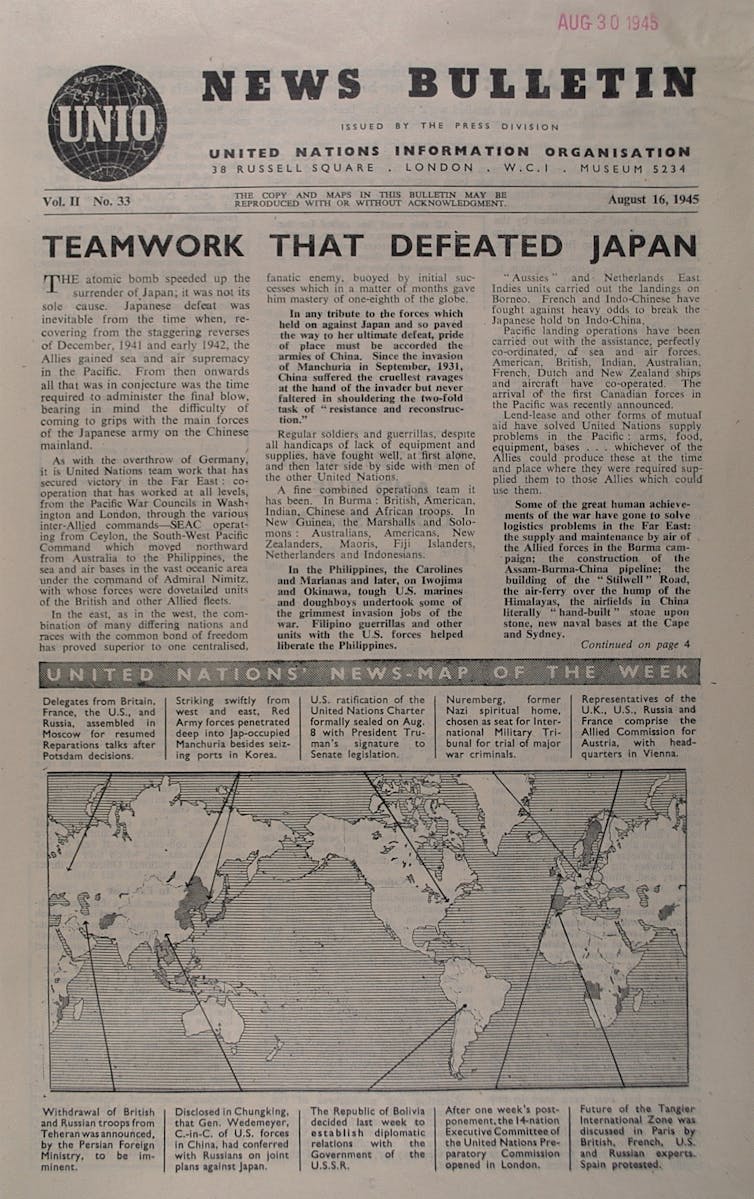

During World War II, Nazi Germany occupied Denmark, and the U.S. assumed the role of protector of both Greenland and Iceland, both of which belonged to Denmark at the time. The U.S. built airstrips, weather stations and radar and communications stations – five on Greenland’s east coast and nine on the west coast.

Thomas Traasdahl/Ritzau Scanpix/AFP via Getty Images

The U.S. used Greenland and Iceland as bases for bombers that attacked Germany and German-occupied areas. Greenland had a high value for military strategists because of its location in the North Atlantic – to counter Nazi threats to Allied shipping lanes and protect transatlantic routes, and because it was a midpoint for refueling U.S. aircraft. Greenland’s importance also rested on its deposits of cryolite, useful for making aluminum.

In 1946, the Truman administration offered to buy Greenland for $100 million, as U.S. military leaders thought it would play a critical role in the Cold War.

The secret U.S. project Operation Blue Jay at the beginning of the Cold War resulted in the construction of Thule Air Base in northwestern Greenland, which allowed U.S. bombers to be closer to the Soviet Union. Renamed Pituffik Space Base, today it provides a 24/7 missile warning and space surveillance facility that is critical to NATO and U.S. security strategy.

At the end of World War II, Denmark recognized Greenland as one of its territories. In 1953, Greenland gained constitutional rights and became a country within the Kingdom of Denmark. Greenland was assigned self-rule in 1979, and by 2009 it became a self-governing country, still within the Kingdom of Denmark, which includes Denmark, Greenland and the Faroe Islands.

Denmark recognizes the government of Greenland as an equal partner and recently gave it a more significant role as the first voice for Denmark in the Arctic Council, which promotes cooperation in the Arctic.

What the US may want

The Trump administration’s 2025 National Security Strategy identifies three threats in the Western Hemisphere: migration, drugs and crimes, and China’s increasing influence.

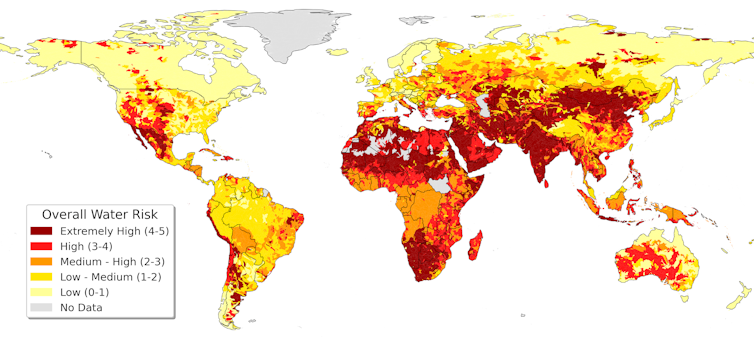

Two of those threats are irrelevant when considering Greenland. Greenlandic people are not migrating to the U.S., and they are not drug traffickers. However, Greenland is rich in rare earth minerals, including neodymium, dysprosium, graphite, copper and lithium.

Additionally, China seeks to establish mining interests in Greenland and the Arctic as part of its Polar Silk Road initiative. China had offered to build an infrastructure for Greenland, including improving the airport, until Denmark stepped in and offered airport funding. And China has worked with Australian companies to secure mining opportunities on the island.

James McAnally/Archive Photos/Getty Images

Those rare earth minerals appeal to the European Union, too. The EU lists some 30 raw materials that are essential for their economies. Twenty-five are in Greenland.

The Trump administration has made it clear that controlling these minerals is a national security issue, and the president wants to keep them away from China.

Figures vary, but it is estimated that over 60% of rare earth elements or minerals are currently mined in China. China also refines some 90% of rare earths. This gives China tremendous leverage in trade talks. And it results in a dangerous vulnerability for the U.S. and other nation states seeking to modernize their economies. With few suppliers of these rare earth elements, the political and economic costs of securing them are high.

Greenland has only two operating mines. One is the Tan Breez project in southern Greenland. It produces 17 metals, including terbium and neodymium, that are used in high-strength magnets used in many green technologies and in aircraft manufacturing, including for the F-35 fighter planes.

Consider for a moment that Trump is not interested in owning Greenland.

Instead, he is using this threatening position to secure promises from the Greenlandic government to make economic deals with the U.S. and not China. Thus, Trump’s threats could be less about national security and much more about eliminating competition from China and securing wealth for U.S. interests.

This form of coercive diplomacy threatens the political and economic development of not only Greenland but Europe. In recent interviews, Trump has made it clear that he does not respect international law and the sovereignty of countries. His position, I believe, undermines the international order and removes the U.S. as a responsible leader of that framework established after World War II.

![]()

Steven Lamy does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Trump’s stated reasons for taking Greenland are wrong – but the tactics fit with the plan to limit China’s economic interests – https://theconversation.com/trumps-stated-reasons-for-taking-greenland-are-wrong-but-the-tactics-fit-with-the-plan-to-limit-chinas-economic-interests-273548