Source: The Conversation – USA (3) – By Rachel Rebouché, Professor of Law, Temple University

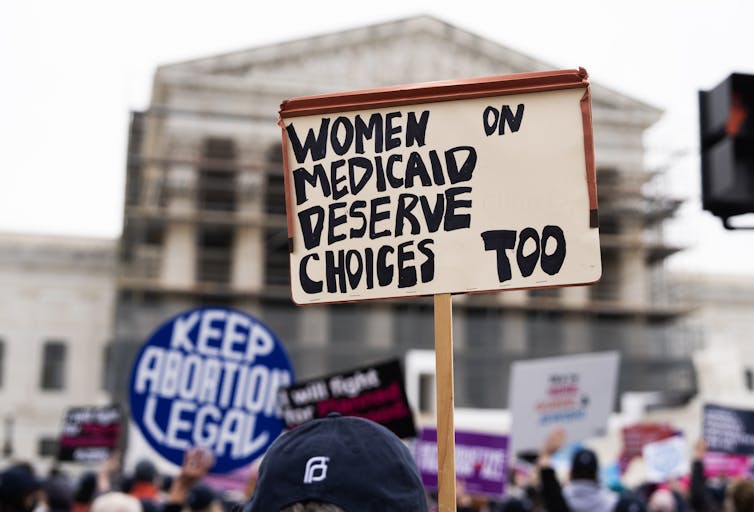

Conservatives have won two important battles in their decades-long campaign against Planned Parenthood, a network of affiliated clinics that are the largest provider of reproductive health services in the U.S.

One of these victories was a U.S. Supreme Court ruling handed down on June 26, 2025. The other is a provision in the multitrilion-dollar tax-and-spending package President Donald Trump has made his top legislative priority. Both follow the same strategy: depriving Planned Parenthood – and all other providers of abortion care – from getting reimbursed by Medicaid, the government health insurance program that mainly covers low-income adults and children, as well as people with disabilities.

Because Medicaid covers nearly 80 million Americans, this bill, and the Supreme Court’s decision, will sever federal support for health care that has nothing to do with abortion, such as annual exams, birth control and prenatal care. Abortions account for 3% of all of Planned Parenthood’s services.

As a scholar of reproductive rights, I have studied how abortion politics shape the broader provision of reproductive health care.

I see in both the legislation and the court’s ruling a culmination of a strategy to defund Planned Parenthood that was in full swing by 2007, toward the end of the George W. Bush administration. This campaign hinges on a strategy of insisting that federal and state dollars are supporting abortion care when they do not.

Angela Weiss/AFP via Getty Images

Congress and the Supreme Court

Trump’s package of tax breaks, spending increases and safety net changes passed in the House and the Senate by razor-thin margins.

One of the bill’s provisions will make it impossible for patients with Medicaid coverage to get any health care services at clinics like Planned Parenthood.

The provision will last only for a year.

The House approved the same version of the package that the Senate had passed a week after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that states cannot be sued by patients if they make it impossible for Planned Parenthood clinics to be reimbursed by Medicaid.

The case, Medina v. Planned Parenthood South Atlantic, arose when a South Carolina woman wanted to get gynecological care at her local Planned Parenthood clinic. The rationale South Carolina Gov. Henry McMaster gave for the state’s policy was that Planned Parenthood is an abortion provider.

Kayla Bartkowski/Getty Images

Medicaid and abortion

To be clear, neither the legal dispute nor the provision in the legislative package had anything to do with the use of federal or state dollars to fund abortion.

Although Planned Parenthood offers abortion where and when it is legal, this provision and the court’s decision concern Medicaid reimbursement for all other services. Abortion care is not covered by Medicaid under federal law except in cases of rape, incest or a threat to the pregnant patient’s life.

Medicaid patients instead have relied on their plan at Planned Parenthood clinics when they get annual exams, prenatal care, mental health support, birth control, treatment for sexually transmitted infections, cervical cancer screenings and fertility referrals.

None of those services will be covered by Medicaid for a year. Patients will have to find another health care provider – as long as one is available.

While that provision is in effect, Medicaid won’t be allowed to reimburse Planned Parenthood for any services, mirroring what states just won the right to do in the Supreme Court ruling – but at the national level.

Although the bill blocks Medicaid funding for Planned Parenthood for only 12 months, the ruling lets states exclude any provider from its Medicaid program because they also provide abortions.

In other words, people who rely on Medicaid funding will lose access to all of those essential services not just at Planned Parenthood but potentially at any other providers that also offer abortion care.

Given the number of states that ban almost all abortion, I have no doubt that more states will do that, especially if this Medicaid funding provision expires after a year without being renewed.

Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call via Getty Images

Roots of this defunding strategy

Politicians began to call for defunding Planned Parenthood about 20 years ago, following efforts by anti-abortion activists to discredit the organization altogether.

U.S. Rep. Mike Pence introduced the first federal legislation aimed at “defunding” Planned Parenthood in 2007. It failed to muster enough support in Congress to become law. States such as Texas then started down that path.

The first national legislative success came in 2015. Both houses of Congress passed a budget reconciliation measure with a provision to defund Planned Parenthood that year, but President Barack Obama vetoed it. Republicans had threatened to shut down the government over those demands. A year later, the GOP included a call to defund Planned Parenthood in its presidential campaign platform.

Before Obama left office, his administration passed a rule in December 2016 protecting federal funds for family planning for health care facilities that also provided abortion. The Trump administration rolled back that rule in 2017.

The Trump administration relied on an argument that any support for a health care provider that offers patients abortion services, no matter how segregated the sources of funding, is tantamount to subsidizing abortion.

What to expect next

Nationally, 16 million women of reproductive age rely on Medicaid, and 1 in 5 women will visit a Planned Parenthood clinic for health care at least once in their lives. Those clinics depend on Medicaid reimbursement to offer an array of reproductive health care services, such as prenatal care, that are not tied to abortion.

If Planned Parenthood clinics can’t bill Medicaid for those services, many will close. Planned Parenthood estimates that it could see almost 200 closures – 90% of them in states where abortion is legal. That means over 1 million low-income people risk losing access to their health care provider.

And once clinics close, they may never reopen, U.S. Sen. Patty Murray, a Washington Democrat, recently predicted.

Should the number of Planned Parenthood clinics plummet, it will threaten access to contraceptives, which are all the more important in preventing unwanted pregnancies for people living in states that have banned abortion. Researchers have repeatedly found that unwanted pregnancies, when people are denied access to abortion services, are correlated with increased debt, missed educational and employment opportunities, mental health problems, and diminished care for a family’s older children.

In addition, pregnant patients and new parents may have more limited options for prenatal and postnatal care. That could cause the country’s already-high rates of maternal and infant mortality to increase.

![]()

Rachel Rebouché does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Conservatives notch 2 victories in their fight to deny Planned Parenthood federal funding through Medicaid – https://theconversation.com/conservatives-notch-2-victories-in-their-fight-to-deny-planned-parenthood-federal-funding-through-medicaid-260233