Source: The Conversation – UK – By Jon Gluyas, Professor of Geoenergy, Carbon Capture and Storage, Durham University

Imagine powering long-haul aircraft and heavy ships with fuels derived from just air, water and renewable electricity. This is moving from science fiction to the verge of reality, thanks to the falling price of renewables like wind and solar.

Whereas burning today’s fuels releases carbon into the atmosphere that has been sequestered underground for millions of years, these “e-fuels” would be more environmentally friendly, adding and subtracting carbon from the air in roughly equal quantities.

We’re seeing a glimpse of the future in HIF Global’s Haru Oni project in the south of Chile, backed by Porsche and ExxonMobil. It uses wind power to produce synthetic methanol and gasoline, marking one of the first commercial e-fuel ventures. Similar projects are under development in North Africa, Iceland and the Arabian peninsula, targeting export of e-methanol and e-kerosene.

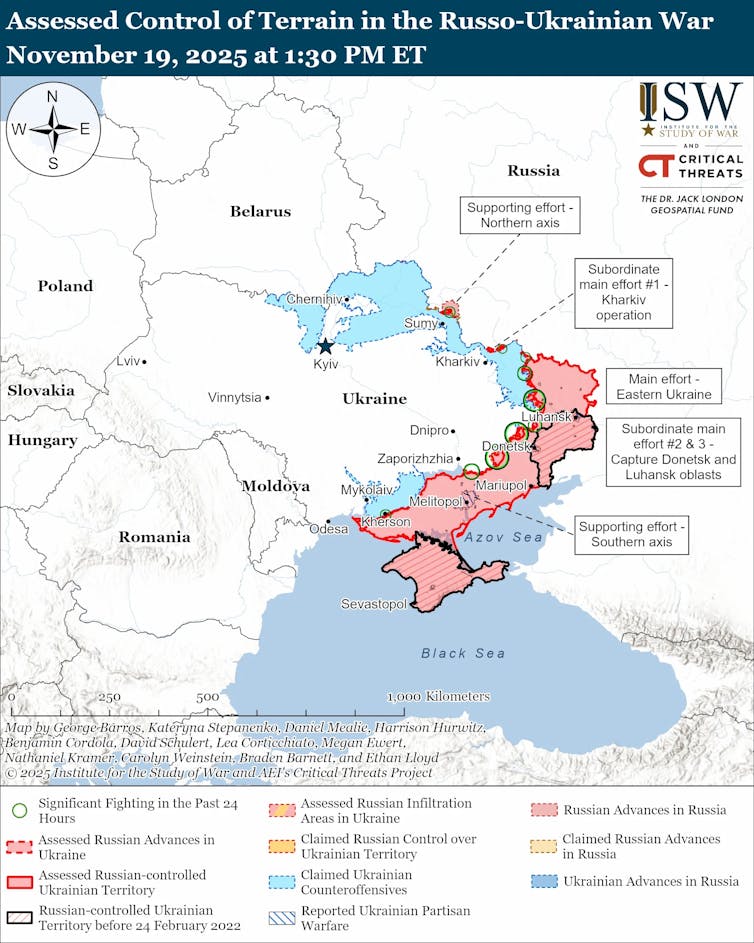

E-fuels sit within the broader category of synthetic fuels, which are vital for sectors like aviation and shipping that won’t be able to switch to electric power or clean fuels such as hydrogen any time soon.

Synthetic fuels are chemically similar to the energy-dense liquid fuels these modes of transport currently rely on, though its equally possible to produce gases. They still only comprise a tiny share of fuels in these sectors – for instance, around 0.3% of global jet engine fuel was synthetic in 2024.

This is expected to change dramatically in the coming years, potentially rising as high as 50% by 2050. In the meantime, each synthetic fuel comes with trade-offs that affect their costs, scalability and the time to reach the market.

The alternatives

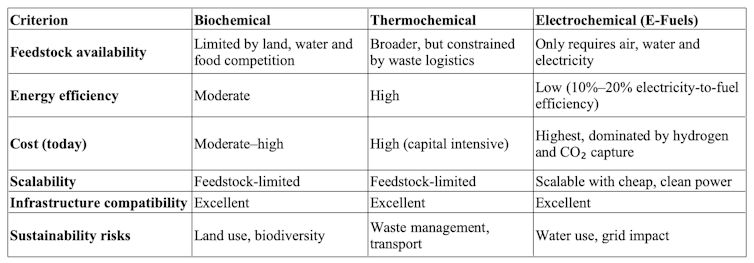

The two other main varieties of synthetic fuel are known as biochemical and thermochemical.

Biochemical fuels are derived either from processing waste fats and oils, or using fermentation or enzymes to transform things like crops and organic waste into alcohols. In both cases, there’s a final step that involves adding hydrogen, in a process called catalytic hydrogenation.

The supply chains are well established for this kind of production, but there’s a lot of competition for the raw materials. They have to be grown on land or water that would otherwise be used for food. Even under optimistic assumptions, these won’t satisfy global demand for sustainable fuels alone.

Thermochemical production uses high temperatures to convert wood residues, waste biomass or even plastics into syngas (a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen). This is then converted into liquid fuels through an industrial process such as Fischer–Tropsch, in which they are heated and run over a catalyst like cobalt.

There’s no need for food feedstocks here, and the industrial processes are proven. However, you must still collect and transport large volumes of feedstock, while the high-temperature plants are expensive. As it stands, the vast majority of today’s synthetic fuels are therefore biochemical, mostly from reprocessing oils.

E-fuels

E-fuels are the newest option. Many leaders in global energy expect them to play a central role in decarbonising aviation and shipping – especially as biomass feedstocks reach their limits. The challenge is that making e-fuels is energy-intensive and currently expensive, particularly where renewable power is scarce or costly. Here’s how it breaks down:

1. Carbon dioxide capture

Capturing and concentrating CO₂ requires about 1-3 megawatt hours (MWh) of energy per tonne, which is fairly significant. Using commercially supplied CO₂ is about one-third the cost of capturing it from the air, so hybrid approaches that use some commercial CO₂ will probably take off first. Commercial CO₂ is usually a byproduct from burning fossil fuels, so this has an environmental downside.

2. Hydrogen production

Even the best methods for extracting hydrogen from water operate at about 70% efficiency. This means that 50–55 kilowatt hours (kWh) of electricity are needed to produce 1kg of hydrogen, which stores only 33 kWh of chemical energy – in other words, considerably more energy goes in than out. This is one reason why making fuels from electricity will probably never be as cheap as using direct electrical power.

3. Compression, storage and transport

Hydrogen must be compressed or liquefied, consuming additional energy (for example, around 10–13 kWh per kg of hydrogen for liquefaction). Hydrogen is also prone to leakage and can embrittle steel pipelines, making long-distance transport difficult.

4. Converting carbon dioxide to fuel

The captured and concentrated C0₂ is converted into fuel by reacting it with hydrogen – or it can first be reduced to carbon monoxide in a catalytic “fuel synthesis” process. In both cases, the resultant product can be an alcohol such as methanol, or a more complex hydrocarbon such as a mixture of paraffins or waxes. Dependent on the desired final product, further processing may be necessary. These steps require high temperatures and pressures, adding energy demand and capital cost.

In sum, each of these four processes compounds energy losses. Until green electricity gets much cheaper, e-fuels will remain a premium product.

In the US and UK, electricity prices are currently around four times greater than natural gas, whereas in Europe it’s about 2.5 times greater. Roughly speaking, e-fuels will remain more expensive than fossil fuels until these prices reach parity. Electricity prices incorporate manufacturing and distribution costs as well as taxes, so we’ll need reductions across the board.

Synthetic fuels comparison

The good news is that the cost of green power should keep falling as the technology gets more efficient. In aviation, recent analysis predicts that most sustainable fuel will be biochemical or thermochemical until 2040, but after that most growth is likely to come from e-fuels. By 2050, these could make up over half of all synthetic fuels.

Grzegorz Majchrzak

E-fuels could be made in regions rich in renewables such as North Africa, Patagonia and Iceland — creating new players in the global energy trade. A whole ecosystem involving everything from large-scale renewables to fuel logistics will have to be scaled rapidly to make this industry viable.

In short, the chemistry works but the economics are still catching up. And while e-fuels are an exciting prospect, they’re not a silver bullet. Governments and the energy industry will still need to prioritise the switch to electric power and greater energy efficiency wherever possible.

![]()

Jon Gluyas is a named but unremunerated director of sustainable aviation fuels startup Exergic Ltd. There was a significant contribution to this article from Jon’s friend Neil Fowler, a retired industrialist.

– ref. Fuel made from just air, power and water is taking off – but several things are holding it back – https://theconversation.com/fuel-made-from-just-air-power-and-water-is-taking-off-but-several-things-are-holding-it-back-269326