Source: The Conversation – UK – By Ligin Joseph, PhD Candidate, Oceanography, University of Southampton

The final week of November was devastating for several South Asian countries. Communities in Sri Lanka, Indonesia and Thailand were inundated as Cyclones Ditwah and Senyar unleashed days of relentless rain. Millions were affected, more than 1,500 people lost their lives, hundreds are still missing, and damages ran into multiple millions of US dollars. Sri Lanka’s president even described it as the most challenging natural disaster the island has ever seen.

When disasters like this happen, the blame often falls on a failure in early warnings or poor preparedness. This was the case with major floods in Kerala, south India, in 2018, which devastated my hometown.

But this time, the forecasts were largely accurate; the authorities knew the storms were coming, yet the devastation was still immense.

So, if the forecasts were good enough, why were the impacts still so severe?

Weak winds, extreme rain

One emerging explanation is that these storms were not dangerous because of their winds, but because they produced unusually intense rainfall.

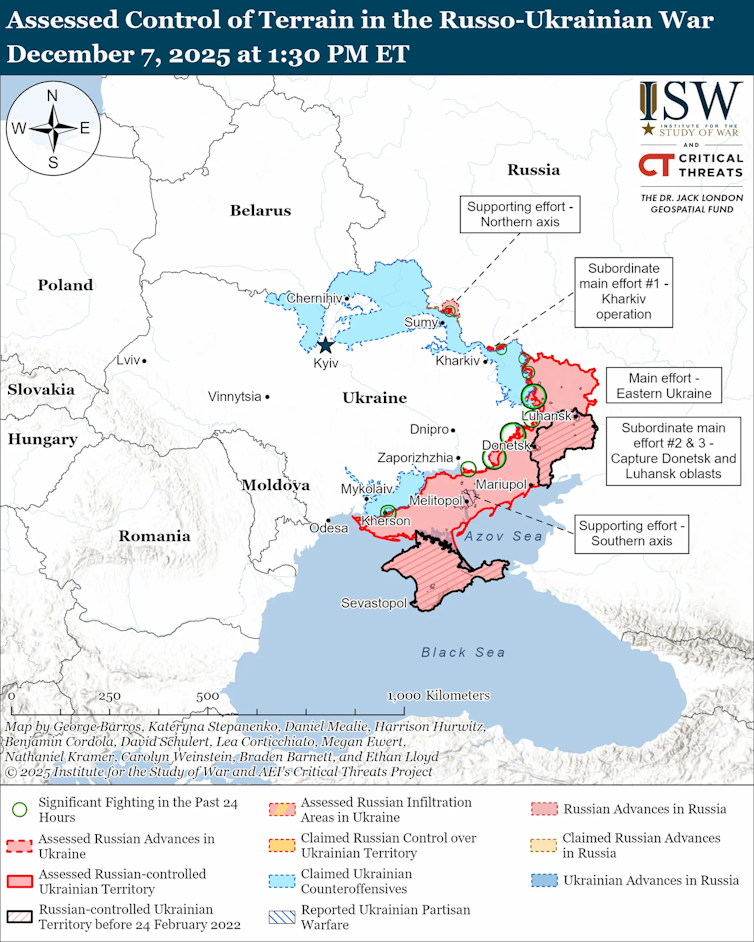

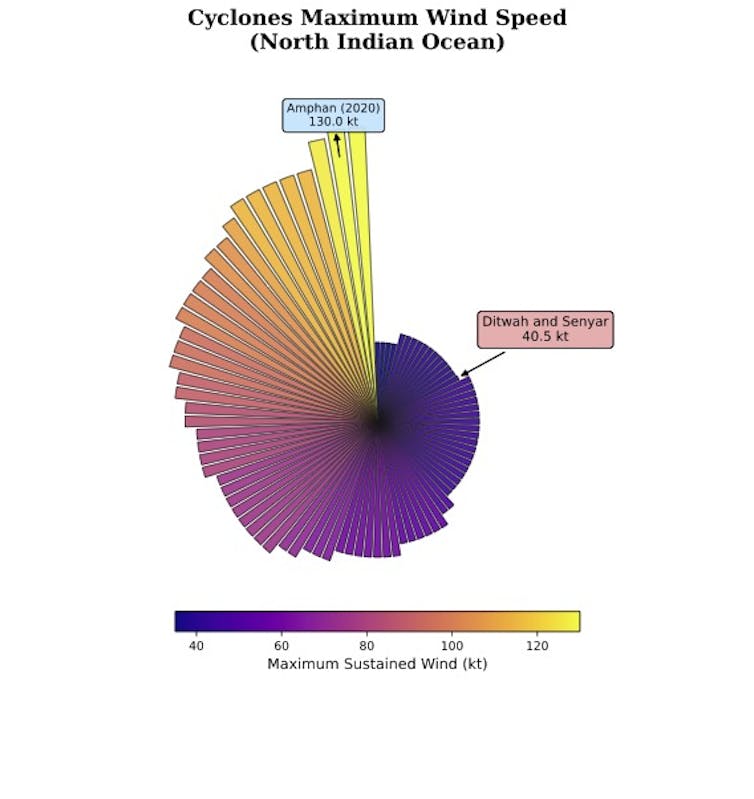

Ligin Joseph (data: IBTrACS), CC BY-SA

Consider Cyclone Ditwah. Its peak winds were around 75 km/h (47 mph). That’s windy, but nothing special. In the UK, it would be classified merely as a “gale” rather than a “storm”. It was far weaker than the 220 km/h winds of the powerful 1978 cyclone that also struck Sri Lanka. Yet Ditwah still caused massive devastation.

What explains this apparent contradiction? It’s too early to say definitively, but climate change is likely a part of the story. Even when storms are not especially strong in wind terms, the amount of rain they carry is increasing.

A warmer atmosphere holds more water

A well established meteorological rule helps explain why. For every degree of global warming, the atmosphere can hold about 7% more moisture.

As the planet warms, the air above us becomes a larger reservoir, waiting to dump more water on us. When storms form, they can tap into this expanded supply, often in extremely short bursts. Even if wind speeds are modest, the rainfall alone can be catastrophic.

The oceans matter even more

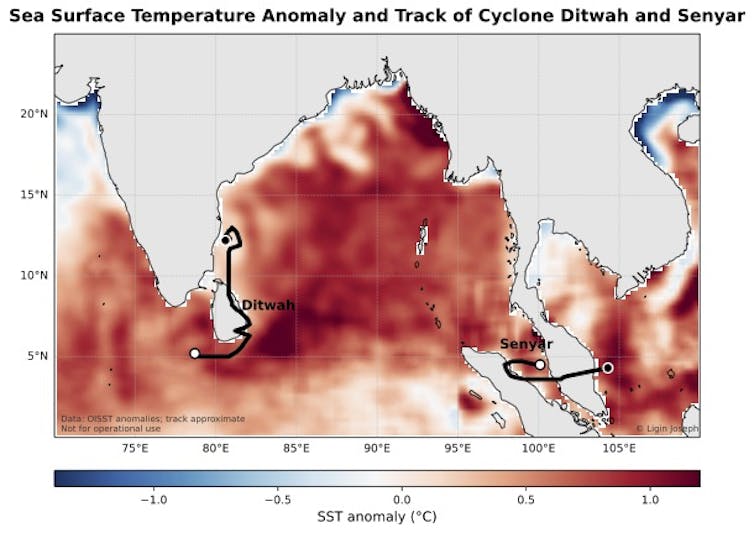

Warming oceans play an even more powerful role, as cyclones draw their energy from warm ocean waters. Satellite data from late November shows just how warm the eastern Indian Ocean was, with large areas more than 1°C above normal during Ditwah and Senyar.

Ligin Joseph (Data: OISST; track positions are approximate), CC BY-SA

Such warm anomalies are no longer unusual. The oceans have absorbed more than 90% of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases, and long-term observations show a clear upward trend in ocean temperatures.

That doesn’t necessarily mean cyclones are becoming more frequent – their formation still depends on other ingredients, such as low wind shear (small differences in wind speed and direction with height) and the right atmospheric structure.

What warmer oceans do change, however, is the amount of energy available to any storm that does manage to form. When the ocean is warmer, cyclones have more fuel and evaporation increases, loading the atmosphere with moisture that can fall as intense rain once a storm develops. Even weak cyclones can therefore hold exceptional amounts of rain.

Ligin Joseph (Data: ERA5), CC BY-SA

The winds near the surface help this process along. As they move across the ocean, they sweep away the moisture-filled air just above the water and replace it with drier air, allowing evaporation to continue. Put together, warmer oceans, higher evaporation, and an atmosphere that can store more moisture, these factors can significantly intensify the rainfall associated with cyclones.

Coastline hugging makes flooding worse

Local geography amplified these effects. Both Ditwah and Senyar formed unusually close to land and travelled along the coastline for an extended period. This meant they stayed over warm waters long enough to continuously draw moisture, but remained close enough to land to dump that moisture as intense rainfall almost immediately.

Cyclone Ditwah, in particular, moved slowly as it approached Sri Lanka. Slow-moving storms can be especially dangerous as they repeatedly dump rain over the same area. Even if winds are weak, this combination of warm seas, coastal proximity and slow forward speed can be devastating.

A new threat

These storms suggest that climate change – especially ocean warming – is reshaping the risks posed by cyclones. The most dangerous storms may no longer simply be the ones with the strongest winds, but also the ones with the most moisture.

Forecasting systems, including new AI-powered weather models, are getting better at predicting cyclone tracks and wind speeds. Yet rainfall-driven flooding remains far harder to forecast. As oceans continue to warm, governments and disaster agencies will need to prepare for storms that may be weak in wind but extreme in rain.

These insights are based on preliminary analysis and emerging scientific understanding. More detailed peer-reviewed studies will be needed to pinpoint exactly why Ditwah and Senyar produced such extreme rainfall. But the pattern that is emerging – weak cyclones delivering outsized floods in a warming world – must not be ignored.

![]()

Ligin Joseph receives funding from the UK’s Natural Environment Research Council (NERC).

– ref. Even ‘weak’ cyclones are being turned into deadly rainmakers by fast-warming oceans – https://theconversation.com/even-weak-cyclones-are-being-turned-into-deadly-rainmakers-by-fast-warming-oceans-271550