Source: The Conversation – UK – By Stephanie Brown, Lecturer in Criminology, University of Hull

A recent YouGov poll found that the word that Americans most associate with the middle ages is “violent”. Medieval towns may appear to be full of random violence, every alleyway a potential crime scene, every tavern brawl ending in bloodshed. But our recent research reveals a more complex, and in some ways familiar, reality.

In 14th-century London, York and Oxford, lethal violence clustered in a small number of hotspots, often no more than 200 or 300 metres long. Just as in modern cities, crime was not evenly spread but concentrated in certain streets and intersections where people, goods and status converged. The surprising difference is that in the middle ages, the busiest and wealthiest areas were often the most dangerous.

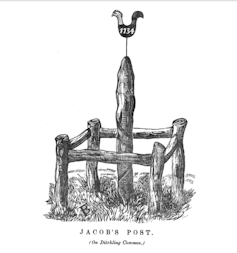

Author provided, CC BY-SA

Our Medieval Murder Map project uses coroners’ inquests (jury investigations into suspicious deaths) to pinpoint the locations of 355 homicides between 1296 and 1398. These records detail where the body was found, when the attack happened, the weapon used, and sometimes the quarrels, rivalries or insults that triggered it.

The cases from the coroners’ records were geocoded (turning a description of a place, like an address, into a pair of numbers, latitude and longitude, to show its exact position) using thematic maps provided by the scientific team of the Historic Towns Trust. What emerges is a vivid street-level picture of urban violence seven centuries ago.

The patterns are striking. Homicides clustered in markets, major thoroughfares, waterfronts and ceremonial spaces. These were areas of intense activity, where economic and social life intersected and where conflicts could be played out before a public audience.

Sundays were particularly deadly. After a morning of churchgoing, the afternoon often brought drinking, games and arguments. Violence peaked around curfew in the early evening.

A tale of three cities

The three cities we looked at differed sharply in their overall levels of violence. Oxford’s homicide rate was three to four times higher than that of London or York.

This was not random. The medieval university attracted young men aged between 14 and 21, many living far from home, armed and steeped in a culture of honour and group loyalty. Students organised themselves into “nations” based on their regional origins and quarrels between northerners and southerners regularly erupted into street battles.

Legal privileges for clerics, which included students, meant that they were often immune from prosecution under common law, creating a climate in which serious violence could flourish with little fear of punishment.

Each city’s hot-spots had their own character. In London, Westcheap, the commercial and ceremonial heart of the city, saw murders linked to guild rivalries, professional feuds and public revenge attacks. The bustling Thames Street waterfront, by contrast, was home to sudden quarrels among sailors and merchants, sometimes escalating from petty disputes into fatal encounters.

In York, one of the most dangerous spots was the main southern approach through Micklegate to Ouse Bridge. This was more than just a gateway into the town – it was a commercial and civic hub, lined with shops and inns, and the site of processions and public gatherings. Such a space naturally drew travellers, traders, and townspeople into close contact and into conflict.

Another York hot-spot was Stonegate, a prestigious street that formed part of the ceremonial route to York Minster. These patterns reflect York’s particular blend of commerce, ceremony and civic life, where spaces of wealth and display doubled as stages for rivalry, revenge and the public assertion of honour.

In Oxford, the concentration of killings in and around the university quarter reflected the constant tensions between students and townspeople and the factionalism within the student body itself. Clashes were often fuelled by drink, insults and a readiness to defend group honour with swords or knives.

The geography of medieval violence was shaped by visibility as much as opportunity. Busy streets and central markets offered the greatest number of potential rivals and bystanders and so were ideal stages for settling disputes in ways that preserved or enhanced reputation. Public killings could send a powerful message, whether to a rival guild, a hostile faction or the wider community.

In this sense, the urban logic of violence in the middle ages echoes patterns found in modern cities, where certain micro-locations consistently generate higher crime rates. The difference is that in medieval England, poverty was not the main driver. Poorer, peripheral neighbourhoods saw fewer homicide inquests, while affluent and prestigious districts often drew the most danger.

The Medieval Murder Map offers a rare opportunity to see the medieval city as its inhabitants experienced it: a landscape where the streets themselves shaped the rhythms of danger, and where wealth, power and proximity could be as deadly as poverty and neglect. Far from being random, medieval violence followed rules – and those rules were written in the geography of the city.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

![]()

Stephanie Brown has received funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC).

Manuel Eisner does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Our medieval murder maps reveal the surprising geography of violence in 14th-century English cities – https://theconversation.com/our-medieval-murder-maps-reveal-the-surprising-geography-of-violence-in-14th-century-english-cities-263380