Source: The Conversation – UK – By Laura O’Flanagan, PhD Candidate, School of English, Dublin City University

A revival of a beloved and notorious Irish play from 1907, Catriona McLaughlin’s production of The Playboy of the Western World treats J.M Synge’s play as a work with urgent contemporary force, creating a story with resonance in 2026.

Reuniting Derry Girls Nicola Coughlan and Siobhan McSweeney at the National Theatre, the play is set in a shebeen (an illicit drinking den) in western Mayo. The plot centres on Pegeen (Coughlan), whose life is jolted by the arrival of Christy Mahon (Éanna Hardwicke).

On the run and boasting that he has murdered his father, Christy becomes an instant local hero. His violent, wild tale of defying his father’s supposed tyranny captivates a community in need of a hero. Christy’s notoriety is quickly complicated by the arrival of his very-much-alive father (Declan Conlon) in act two, collapsing the young man’s carefully constructed myth.

First staged in 1907 in Dublin’s Abbey Theatre, The Playboy of The Western World famously enraged audiences who booed and rioted. At this time, Ireland was moving towards independence and national pride was growing. Irish audiences expected homegrown theatre to showcase a serious, disciplined national character.

Synge’s play, depicting a foolish man whose boasts of patricide are hailed as heroic by a drunken, sexually available community was deemed morally offensive, a direct affront to Ireland itself.

In the intervening century, the play has become recognised as a masterpiece of Irish literature. Synge’s biting dark humour and ear for richly authentic dialogue has endured, with the play now recognised as a classic of modernist drama.

Humour, cruelty and urgency

Told in Hiberno-English (the Irish version of English, influenced by Gaelic) dialogue, The Playboy of The Western World depicts rural life as complex and brutal. Almost 120 years later on a London stage, it rejects a nostalgic view of rural Ireland in a bygone era. These characters are human and imperfect, and just as susceptible to a tall tale as anyone in 2026.

Director Catriona McLaughlin has assembled a cast of familiar Irish names. Nicola Coughlan sparkles as Pegeen. Her sharp tongue and fortitude in a shebeen full of men is edged with frustration and a deep yearning for something exciting to happen.

Éanna Hardwicke’s Christy Mahon begins tightly wound, loosening as he basks in female adoration. His performance is infused with a coiled, elastic physicality giving Christy an electric intensity; Hardwicke dares the audience to fall in love with him, too.

Siobhan McSweeney, characteristically sharp and wickedly funny, is unmissable as the Widow Quin. Providing welcome comic relief are Marty Rea as a slyly humourous Shawn Keogh, and Lorcan Cranitch’s uproariously funny and drunken Michael James.

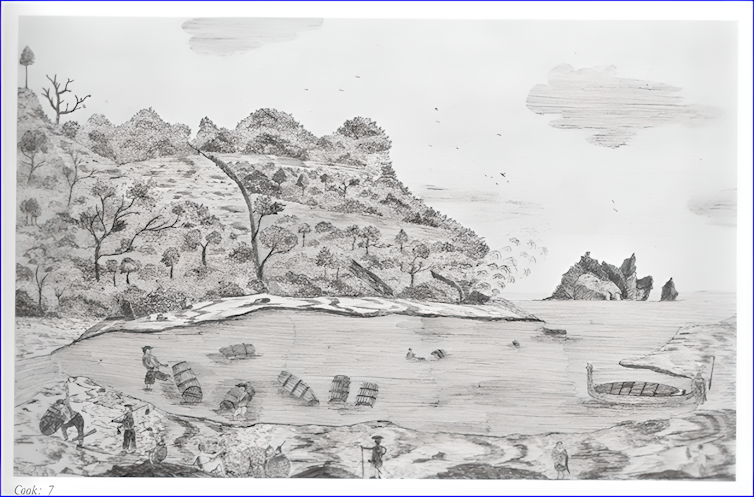

McLaughlin frames the Irish western coast as haunted and mysterious, reinforced by Katie Davenport’s straw mumming costumes (see image below) worn by musicians and extras, and the recurring use of the caoineadh or “keening” – mourning in song.

These design choices create an atmosphere which feels suspended rather than anchored to a particular period. The timelessness sharpens the impact of Christy’s unmasking: the community’s sudden turn against him when they witness a violent act mirrors a familiar real-world pattern. Violence absorbed as story, gossip or spectacle becomes intolerable once its physical reality intrudes.

The crowd’s horror is not prompted by the act itself, but by its visibility. In this way, the production speaks directly to contemporary audiences accustomed to consuming violence at a distance, yet quick to condemn when confronted with its immediate consequences.

Some critics have reported difficulty following Synge’s language, revealing how strongly expectations of “standard” English shape reception. Such dismissals reveal not a failure of intelligibility in the play, but a critical resistance to engaging with Hiberno-English on its own terms.

This requires attention to rhythm, tone and repetition, and dismissing it as unintelligible echoes the play’s broader concern with how stories are received and misread.

Dynamic and intellectually alert, McLaughlin’s production refuses to treat The Playboy of the Western World as a museum piece. It trusts both Synge’s language and its audience, allowing the play’s humour, cruelty and urgency to land without apology. So much more than a revival, this staging reasserts the work’s enduring relevance and makes a compelling case for why it remains essential viewing.

The Playboy of the Western World is at the National Theatre, London, till February 28

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

![]()

Laura O’Flanagan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. The Playboy of the Western World: National Theatre staging ensures Irish play remains essential viewing – https://theconversation.com/the-playboy-of-the-western-world-national-theatre-staging-ensures-irish-play-remains-essential-viewing-274762