Source: The Conversation – UK – By Stefan Wolff, Professor of International Security, University of Birmingham

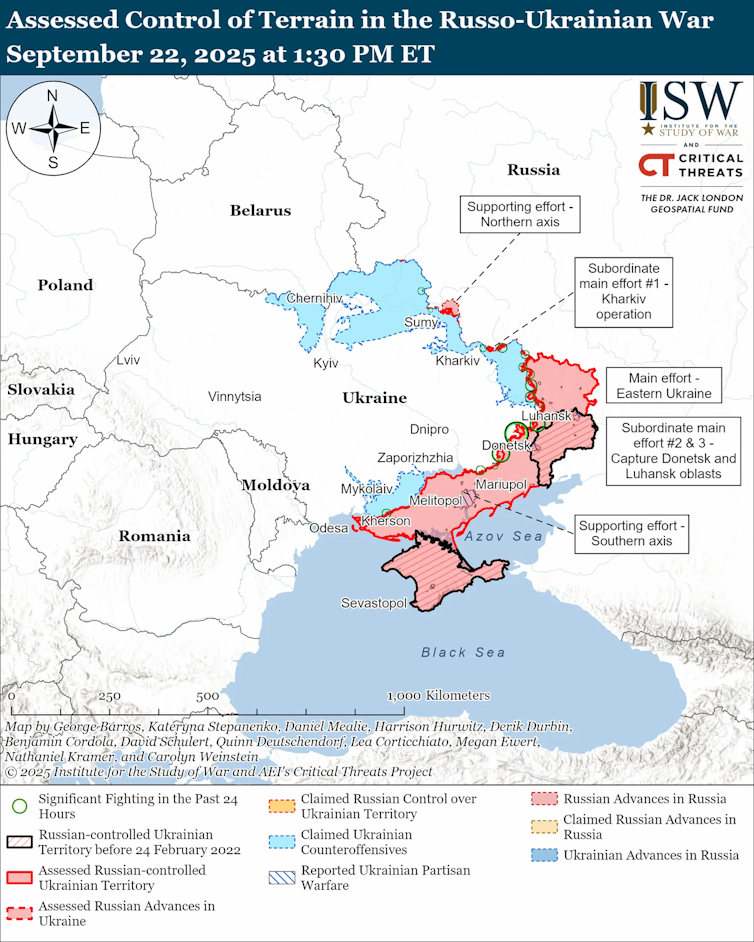

While the air and ground war in Ukraine grinds on, Moscow is increasing pressure on Kyiv’s western allies. Russian drone incursions into Poland in the early hours of September 10, and Romania a few days later, were followed by three Russian fighter jets breaching Estonian airspace on September 19.

And there has been speculation that drones which forced the temporary closure of Copenhagen and Oslo airports overnight are connected to the Kremlin as well.

While this might suggest a deliberate strategy of escalation on the part of the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, it is more likely an attempt to disguise the fact that the Kremlin’s narrative of inevitable victory is beginning to look shakier than ever.

A failed summer offensive that has been extremely costly in human lives is hardly something to cheer about. Estimates of Russian combat deaths now stand at just under 220,000. What’s more, this loss of life has produced little in territorial advances.

Since the start of the full-scale invasion in February 2022, Russia has gained some 70,000 sq km. This means that Moscow has nearly tripled the amount of territory it illegally occupies. But during its most recent summer offensive, it gained fewer than 2,000 sq km. On September 1, 2022, Russia controlled just over 20% of Ukrainian territory, three years later it was 19% (up from 18.5% at the beginning of 2025).

Perhaps most telling that the Russian narrative of inevitable victory is hollow is the fact that Russian forces were unable to convert a supposed breakthrough around Pokrovsk in the Donbas area of Ukraine in August into any solid gains after a successful Ukrainian counterattack.

That Russia is not winning, however, is hardly of comfort to Ukraine. Moscow still has the ability to attack night after night, exposing weaknesses in Ukraine’s air defence system and targeting critical infrastructure.

The western response, too, has been slow so far and has yet to send a clear signal to the Kremlin what Nato’s and the EU’s red lines are. While Nato swiftly launched Eastern Sentry in response to the Russian drone incursion into Poland, the operation’s deterrent effect appears rather limited given subsequent Russian incursions into Estonia and undeclared flights in neutral airspace near Poland and Germany.

ISW

Subsequent comments by Donald Tusk, the Polish prime minister, threatened to “shoot down flying objects when they violate our territory and fly over Poland”. He also cautioned that it was important “to think twice before deciding on actions that could trigger a very acute phase of conflict.”

On the other side of the Atlantic, Donald Trump, the US president, has said little about Russia ratcheting up pressure on Nato’s eastern flank. Regarding the Russian drone incursion into Poland, he mused that it could have been a mistake, before pledging to defend Nato allies in the event of a Russian attack.

This is certainly an improvement on his earlier threats to Nato solidarity, but it is at best a backstop against a full-blown Russian escalation. What it is not is a decisive step to ending the war against Ukraine. In fact, any such US steps seem ever farther off the agenda. The deadline that Trump gave Putin after their Alaska summit to start direct peace talks with Ukraine came and went without anything happening.

Europe scrambles to replace US guarantees

As for Trump’s phase-two sanctions on Russia and its enablers, these have now been made conditional by Trump on all Nato and G7 countries, imposing such sanctions first.

Meanwhile, US arms sales to Europe, meant to be channelled to strengthen Ukraine’s defences, have been scaled down by the Pentagon to replenish its own arsenals.

At the same time, a longstanding US support programme for the Baltic states – the Baltic security initiative – is under threat from cuts. There are justified worries that it could be discontinued as of next year.

As has been clear for some time, support for Ukraine – and ultimately the defence of Europe – is no longer a primary concern for the US under Trump. Yet European efforts to step into the gaping hole in the continent’s security left by US retrenchment are painfully slow. The defence budgets of the EU’s five biggest military spenders – France, Germany, Poland, Italy and the Netherlands – combined are less than one-quarter of what the US spends annually.

Even if money were not the issue, Europe has serious problems with its defence-industrial base. The EU’s flagship Security Action for Europe programme has faced months of delays over the participation of non-EU members – including the UK and Canada, two countries which have significant defence-industrial capacity.

European defence cooperation, including the flagship Future Combat Air System, is threatened by national quarrels, including between the EU’s two largest defence players, France and Germany.

Thus far, muddling through has worked for Ukraine’s western allies. This is mostly because Kyiv has held the line against the Russian onslaught. It has done so by making do with whatever the west provided while rapidly innovating its own defence sector.

It has also worked because Trump has not (yet) completely abandoned his European allies. There is enough life – or perhaps just enough ambiguity – left in the idea of Nato as a collective defence alliance to give Putin pause for thought. For now, he is merely testing boundaries. But if unchallenged, he might keep pushing further into uncharted territory – with unpredictable consequences.

Western stop-gap measures may be fine for now. But the west’s responses to Putin’s challenges – which are likely to become more frequent and more severe in the future – will require the European coalition of the willing to focus on the here and now and raise its level of preparedness.

![]()

Stefan Wolff is a past recipient of grant funding from the Natural Environment Research Council of the UK, the United States Institute of Peace, the Economic and Social Research Council of the UK, the British Academy, the NATO Science for Peace Programme, the EU Framework Programmes 6 and 7 and Horizon 2020, as well as the EU’s Jean Monnet Programme. He is a Trustee and Honorary Treasurer of the Political Studies Association of the UK and a Senior Research Fellow at the Foreign Policy Centre in London.

– ref. Russian incursions into Nato airspace show Ukraine’s allied coalition needs to be ready as well as willing – https://theconversation.com/russian-incursions-into-nato-airspace-show-ukraines-allied-coalition-needs-to-be-ready-as-well-as-willing-265776