Source: The Conversation – UK – By Daniel Kelly, Senior Lecturer in Biochemistry, Sheffield Hallam University

The UK government has announced plans to expand its trial of using drugs to reduce the libido of male sex offenders. The approach, often described as “chemical castration”, is controversial. But how does it work – and what are the risks?

Castration traditionally meant removing or disabling the testes, a man’s main source of testosterone, to blunt the hormone’s masculinising effects. Historically, this was done to create castrati – singers castrated before puberty to preserve their high voices – or eunuchs, often used in royal courts and religious institutions to dampen sexual desire.

Modern castration still has a medical role, particularly in prostate cancer. This disease is fuelled by testosterone, and lowering hormone levels can slow its growth. While surgical removal of the testes was once common, doctors now usually rely on drugs to block testosterone production instead – a method known as chemical castration.

Normally, testosterone is regulated by a feedback loop between the brain, pituitary gland and testes called the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis. The brain signals the pituitary to release hormones that stimulate the testes. Once levels rise, the brain senses it and dials production back down.

Anti-androgen drugs disrupt this system, either by blocking testosterone’s effects or by shutting down the brain’s signals. Drugs such as medroxyprogesterone acetate and cyproterone acetate work by switching off the body’s testosterone supply.

Testosterone is central to libido. It acts on brain regions like the hypothalamus and limbic system, which help drive sexual thoughts, desire and arousal. Reducing testosterone can lower these urges, while also affecting physical aspects of sex, such as the ability to achieve and maintain an erection.

The government’s proposals include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), drugs more commonly prescribed for depression and anxiety. SSRIs increase serotonin in the brain, which can lift mood, but they also reduce sexual desire and performance as a side-effect by interfering with dopamine.

Dopamine is the brain’s main “reward” chemical, strongly linked to pleasure, motivation and sexual behaviour. Serotonin, on the other hand, tends to calm and regulate emotions, often dampening sexual drive. By boosting serotonin, SSRIs can tip this balance – reducing dopamine activity and lowering sexual interest.

When combined with anti-androgens, the two treatments can act on both hormonal and neurological pathways, blunting both the physical and psychological aspects of sex drive.

This dual approach has already been used in other countries. Poland introduced it as a mandatory punishment for certain offenders in 2009, while in south-west England it has been trialled on a voluntary basis, with “successful outcomes” reported.

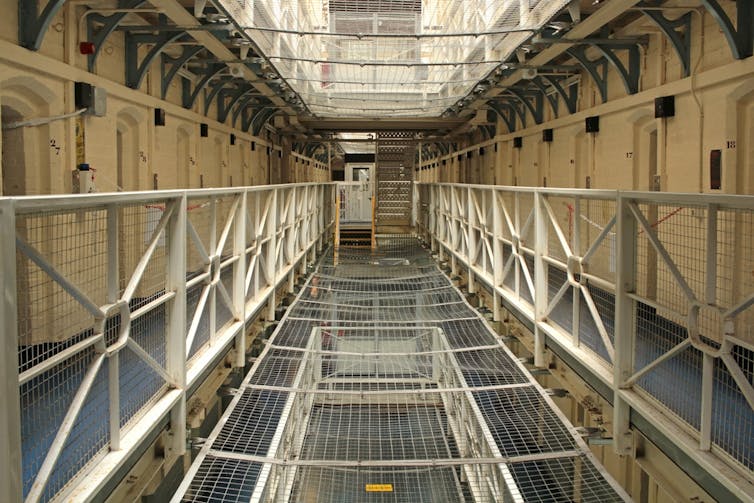

Carol Tyers/Shutterstock.com

Not without risks

The UK’s current proposal is also voluntary, aimed at people struggling with persistent and distressing sexual thoughts that they do not want and actively seek help to control. But while it may reduce reoffending, the treatment is not without risks.

Testosterone plays a vital role in many aspects of health. Long-term suppression has been linked to early death, higher risk of heart attacks and strokes, type 2 diabetes, loss of muscle and bone strength, as well as possible links with Alzheimer’s and breast tissue growth in men.

There are also psychological risks. Testosterone influences mood, and its suppression has been associated with higher rates of depression and even suicidal thoughts and behaviour.

Chemical castration may well prove useful in preventing future sexual offences. But policymakers must weigh its benefits against serious health risks. And given the already high rates of mental health problems among offenders, there is concern that some may not fully understand the consequences of long-term testosterone suppression – physically, psychologically and socially.

![]()

Daniel Kelly does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. UK expands chemical castration pilot programme for sex offenders – but what are the risks? – https://theconversation.com/uk-expands-chemical-castration-pilot-programme-for-sex-offenders-but-what-are-the-risks-266026