Source: The Conversation – UK – By Ligin Joseph, PhD Candidate, Oceanography, University of Southampton

Across India, torrential rains over the past few months have swallowed an entire village in the Himalayas, flooded Punjab’s farmlands and brought Kolkata to a standstill. This all happened in a monsoon season in which total rainfall was technically only 8% above normal.

Climate change is not simply making India’s monsoon wetter. It’s making it wilder – with longer dry spells and more extreme downpours.

The Indian summer monsoon, which delivers about 80% of the country’s annual rainfall, usually sweeps in from the Arabian Sea in early June and retreats at the end of September. Growing up in India, I remember the joy of watching the rains arrive each year, the scent of wet earth and the relief they brought after a scorching April and May. Those memories still live in me. But today, the same monsoon that once filled our rivers and hearts with hope now brings fear and uncertainty.

This year, the monsoon arrived a week early, the fastest onset in 16 years. However, an early start does not necessarily translate to higher rainfall totals for the season. The modest 8% above average hides the real story: many regions experienced unusually intense and frequent downpours.

In the Himalayan village of Dharali, for instance, a cloudburst in early August triggered flash floods that left the local market buried under sediment as high as a four-storey building. Most parts of the village were completely washed away. Scientists suspect melting glaciers and cloudbursts – both linked to a warmer climate – were to blame.

In Punjab, a state of 30 million people often called India’s “food bowl”, heavy rains drowned crops across an area roughly the size of Greater Manchester. All 23 districts of the state were affected.

Scientists say the deluge was driven by an unusual interaction between regular monsoon weather systems and “western disturbances” – storm systems that originate in the Mediterranean and typically influence India’s weather in the winter. Their overlap this year amplified rainfall across northern India.

On the other side of the country, the huge city of Kolkata was not spared either. Some areas received 332mm of rain in just a few hours, more than half of what London gets in a whole year. The rains fell just before the major Hindu festival of Durga Puja, paralysing the city. The culprit was another low-pressure system that formed over the Bay of Bengal and carried vast amounts of moisture inland.

While the south escaped the worst flooding, cities such as Mumbai and Vijayawada also saw intense cloudbursts, demonstrating the spread of extreme rainfall.

Why the monsoon is becoming more extreme

Each disaster was driven by the same underlying trend: a warmer atmosphere that can hold more moisture. For every degree of warming, the air can store about 7% more water vapour – and when that moisture is released, it falls in heavier downpours over shorter periods. This trend is now clearly visible in India’s monsoon data.

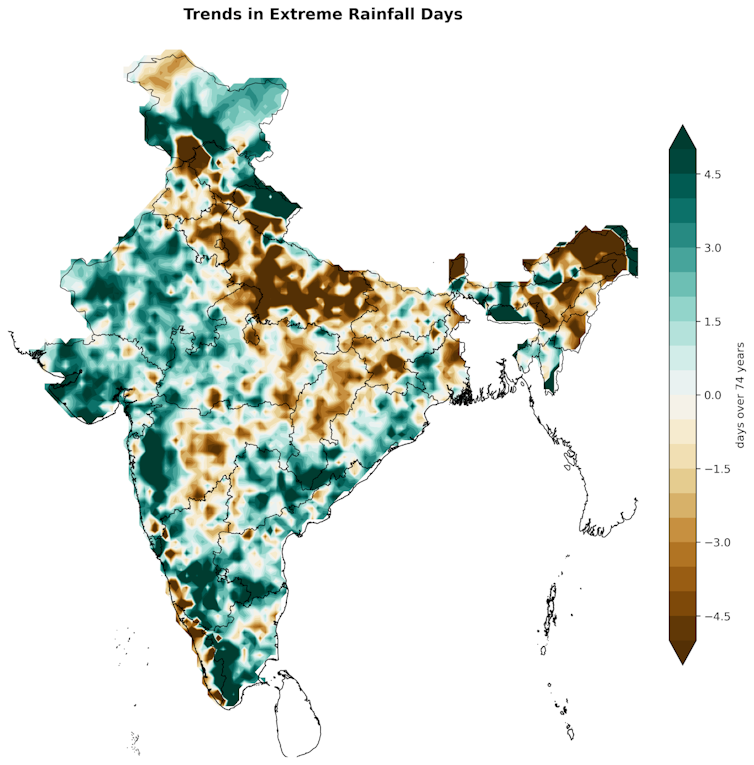

Ligin Joseph (data: Indian Meteorological Department)

The number of extreme rainfall days, when daily totals exceed the top 10% of the long-term average, has risen sharply across southern and western India since the 1950s. Some regions, meanwhile, are receiving less overall rain but in stronger and more erratic bursts, meaning both droughts and floods can be a threat in the same season.

Scientists have also noticed shifts in the monsoon’s circulation and in the low-pressure systems that drive it. Climate change is pushing the whole monsoon system westward, increasing rainfall over typically arid northwestern India, while decreasing rainfall over the traditionally wetter northeast.

All this extreme rainfall is turning the monsoon from a friend into a foe. Unless we act responsibly to limit greenhouse gas emissions and become more resilient to the consequences of a changing climate, the season that sustains life across India may increasingly threaten it.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 45,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

![]()

Ligin Joseph receives funding from the UK’s Natural Environment Research Council (Nerc).

– ref. India’s monsoon is becoming more extreme – even though overall rainfall has hardly increased – https://theconversation.com/indias-monsoon-is-becoming-more-extreme-even-though-overall-rainfall-has-hardly-increased-267159