Source: The Conversation – UK – By Amber Yeoman, Postdoctoral Research Associate in Atmospheric Emissions, University of York

Awaab Ishak, a two-year-old child, died in 2020 after prolonged exposure to mould in his social housing association home. The inquest into his death found that, despite repeated reports by his parents about the property’s uninhabitable conditions, their concerns were dismissed and the housing association failed to take sufficient action.

In response to his tragic death, new legislation known as Awaab’s law now requires social housing associations in the UK to urgently address “all damp and mould hazards that present a significant risk of harm to tenants”.

This is a positive step forward in tackling damp and mould in social housing rented accommodation, which significantly contributes to poor indoor air quality. It also recognises that building occupants cannot always take the necessary actions to improve air quality themselves.

Read more:

Awaab’s law is a start but England needs whole new approach to ensure healthy homes for all

Efforts to maintain good indoor air quality often focus on changing individual behaviour, such as opening windows, using extractor fans and running dehumidifiers or air cleaners. While these measures can help, they are not always affordable or effective on their own. Even when occupants know there is a serious indoor air quality issue, which can have many sources such as mould, heating systems and building materials, they may lack the capability to do anything about it. This was the case for Awaab and his family, as the social housing association refused to act.

Our 2025 research paper explores how people’s ability – or capability – to make changes that improve air quality varies depending on housing tenure (for example, private rental, social housing, owner-occupied). In this context, capability refers to the level of control someone has to alter conditions that affect indoor air, such as fixing damp, improving ventilation, or replacing pollutant-emitting materials.

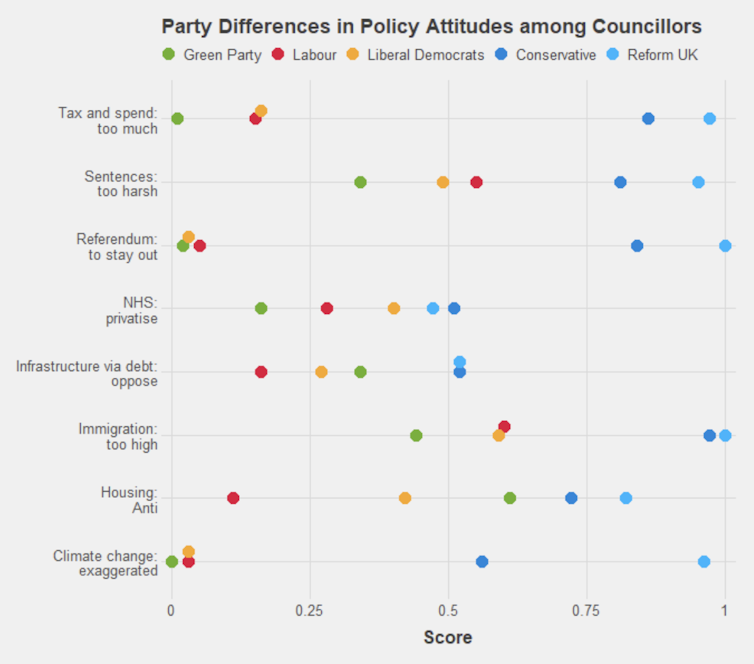

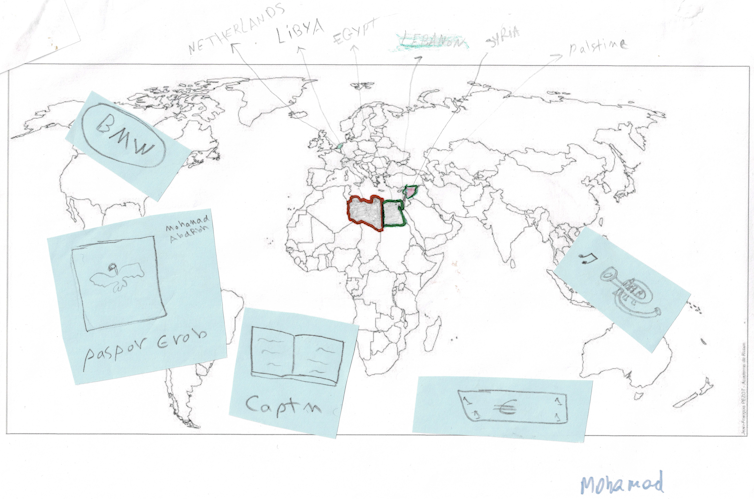

The figure below, also from our paper, shows the link between housing tenure type and capability. The blue bar represents the proportion of the English population living in each tenure type. The red bar below it shows how much control people have over sources of poor indoor air quality, with the most control on the right and the least on the left. Each box within the red bar represents a different activity or source that impacts air quality indoors.

Only one-third of these activities are accessible to those who do not own their home. Even property owners are often unable to influence major factors, such as the materials their house is built from or the outdoor air quality in their area. The activities that offer the least control, such as upgrading insulation, replacing heating systems, or renovating walls and floors to remove pollutant-emitting materials, usually require significant resources such as money, time and space. This highlights how unreasonable it is to blame household air quality issues on lifestyle choices when so many factors are outside an occupant’s control.

Awaab’s law acknowledges that renters face barriers to preventing and fixing damp and mould. It requires social housing associations to respond promptly to all reports of damp and mould, and it explicitly states that it is unacceptable to assume that these problems are caused by a tenant’s lifestyle. Housing associations are also prohibited from using lifestyle as an excuse for inaction.

In the future, Awaab’s law will expand to cover other hazards that tenants cannot easily control, such as extreme temperatures, falls, explosions, fires and electrical risks. However, it does not yet address other causes of poor indoor air quality, including building and decorating materials, heating systems and cooking practices. These sources can emit pollutants such as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) – gases released from paints, varnishes, cleaning products and furniture – and particulate matter – tiny solid or liquid particles produced by activities such as cooking, heating and burning candles. Both can enter the lungs and bloodstream, contributing to breathing problems, allergies, heart disease and, over time, even cancer. These pollutants, then, can be just as harmful to health as damp and mould.

But, unlike mould, which can usually be identified by sight or smell, these pollutants often go unnoticed. A lack of understanding about these pollutants and their sources limits what occupants can do to improve air quality in their homes. So it is essential that people have access to clear information about potential pollutant sources, such as the products and furniture they buy. If this information is not readily available, the responsibility unfairly falls back on occupants once again.

Awaab’s law is an important recognition that tenants are not solely responsible for damp and mould in their homes. It will help protect some of the most vulnerable people living in uninhabitable conditions, yet it stops short of addressing other contributors to poor indoor air quality.

Understanding and tackling these wider issues would benefit everyone, regardless of housing tenure. These broader structural factors include the age and design of buildings, the quality of construction materials, housing regulations, and the social inequalities that limit tenants’ ability to make improvements. Until these underlying conditions are addressed, indoor air quality in the UK will not truly improve.

![]()

Amber Yeoman receives funding from UKRI and Defra.

Douglas Booker is the Co-Founder and CEO of NAQTS Ltd, a business that develops tools and technologies to provide holistic indoor air quality information. He receives funding from UKRI, NIHR, and EPSRC. He is affiliated with the Clean Air Champions team as part of SPF Clean Air Programme.

Faisal Farooq does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Who controls the air we breathe at home? Awaab’s law and the limits of individual actions – https://theconversation.com/who-controls-the-air-we-breathe-at-home-awaabs-law-and-the-limits-of-individual-actions-268060