Source: The Conversation – Global Perspectives – By Darius von Guttner Sporzynski, Professor of History, Australian Catholic University

A new evolutionary study has found human penises are large compared with other primates: for two reasons. The first is reproduction. The second is that size works as a signal, attracting potential mates and intimidating rivals. In evolutionary terms, the penis is big because it is meant to be noticed.

That finding lands awkwardly in a world that has spent centuries hiding, shrinking, censoring or symbolically neutralising the penis whenever it becomes too visible.

A single object captures this tension between biological display and cultural embarrassment: the fig leaf.

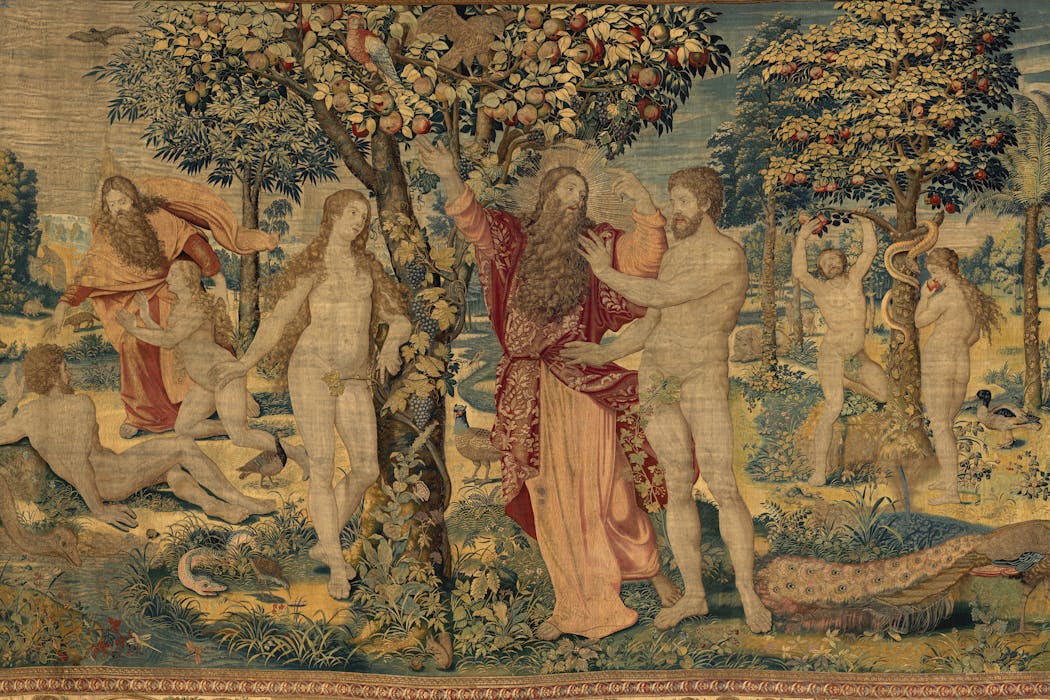

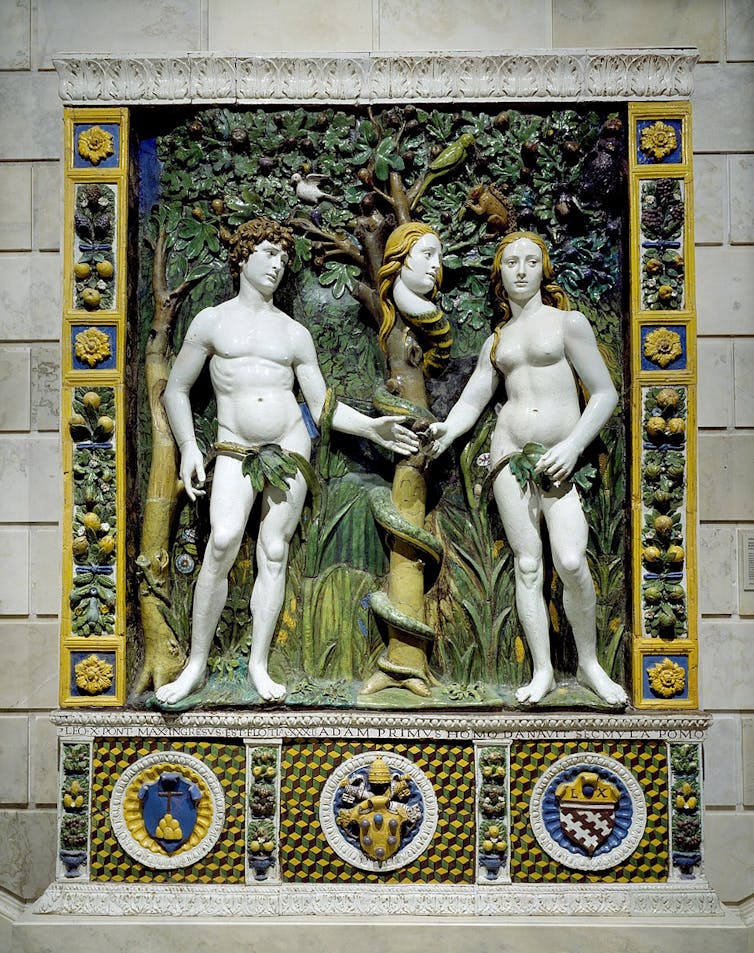

The fig leaf’s story begins, as so many Western stories do, in Genesis. Adam and Eve eat from the tree of knowledge, realise they are naked, and stitch fig leaves together to cover themselves. Nakedness becomes linked with moral awareness, guilt and self-consciousness.

Nudity no longer neutral

Early Christian art absorbed this lesson. In late antique mosaics and medieval manuscripts, Adam and Eve clutch leaves over their groins with a mixture of alarm and regret. Nudity is no longer neutral. It signals sin, punishment, or humiliation. The only bodies shown naked are the damned.

Wikimedia Commons

Then comes a sharp reversal. Ancient Greek and Roman sculpture, rediscovered in Renaissance Italy, presents the naked male body as strong, balanced, and admirable. Heroes, gods, and athletes are unclothed because they have nothing to hide. Their genitals are visible, proportioned, and unremarkable. This is not erotic display so much as confidence made stone.

Michelangelo’s David sits squarely in this tradition. Carved between 1501 and 1504, he is naked, alert and physically present. His body is not idealised into abstraction. It is specific, human, and unmistakably male. Florentines reportedly threw stones when the statue was first installed. Before long, authorities added a garland of metal fig leaves to protect public sensibilities, which remained in place until around the 16th century.

This was not an isolated decision. Over the next century, the Reformation fractured Christian Europe, giving birth to Protestantism, and the Catholic Church doubled down on moral discipline. Naked bodies in art became political liabilities. The Council of Trent’s decrees on religious imagery reflected concerns that the prominent display of naked bodies in sacred art risked drawing attention to human physicality rather than directing devotion towards God. This led to what later historians have called the “Fig Leaf Campaign”.

Across Rome and beyond, sculpted genitals were chipped away, painted over, draped, or concealed with leaves. Michelangelo’s Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel was altered after his death by Daniele da Volterra, who was hired to cover up visible genitalia with drapery. He earned the nickname “the breeches maker” for his efforts.

Classical statues in the Vatican acquired permanent marble underwear. A literal drawer of removed stone penises is rumoured to have existed. Whether or not that is true, the impulse behind it certainly was.

Strikingly, the fig leaf does not erase the penis. It points to it. The cover announces the presence of something that must not be seen. As several writers note, concealment tends to sharpen attention rather than dull it. The fig leaf becomes a visual alarm bell.

Resisting biology

This brings us back to the present. The new evolutionary research argues human penis size evolved partly because it is visible.

For most of our species’ history, before clothes, the penis was on display during daily life. It became a cue others learned to read quickly and unconsciously. Larger size was associated with attractiveness and with competitive threat.

From that perspective, centuries of fig leaves look less like moral refinement and more like cultural resistance to biology. The body insists on signalling. Society keeps trying to mute the signal.

V&A Museum/Wikimedia, CC BY

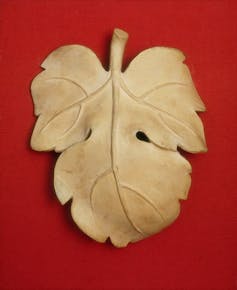

Victorian Britain provides a late and almost comic example. When Queen Victoria was presented with a plaster cast of David, in around 1857, a detachable fig leaf was hastily produced and kept on standby for royal visits.

The leaf survives today, displayed separately in the Victoria and Albert Museum. The statue stands naked again, but the object designed to hide him has become a museum piece in its own right.

Even now, museums still debate whether to remove historic coverings. Social media platforms struggle to define what kinds of nudity are acceptable. Statues are boxed up for diplomatic visits. The anxiety persists, even if the fig leaf itself has become unfashionable.

Evolutionary biology suggests the human penis became prominent because it mattered socially – but our cultural history shows centuries of effort devoted to pretending it does not. The fig leaf sits at the centre of this contradiction: a small, awkward object carrying an enormous cultural load.

![]()

Darius von Guttner Sporzynski does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. The penis evolved to be noticed – but the artful fig leaf has hidden it for centuries – https://theconversation.com/the-penis-evolved-to-be-noticed-but-the-artful-fig-leaf-has-hidden-it-for-centuries-274286