Source: The Conversation – Canada – By Samuel Starko, Forrest Research Fellow, School of Biological Sciences, The University of Western Australia

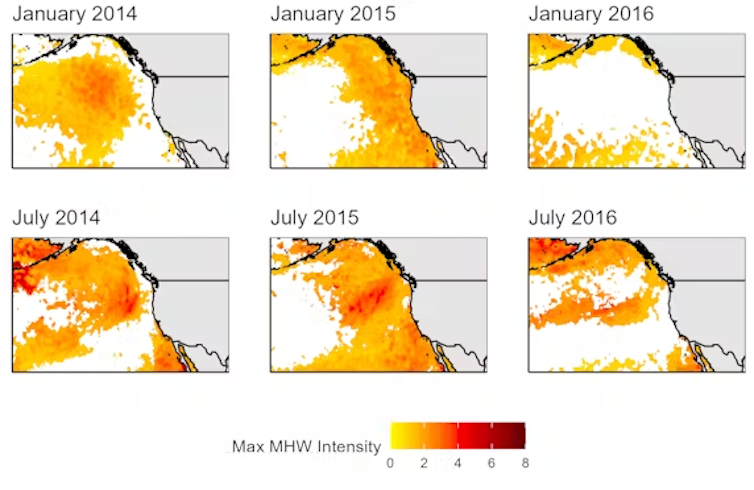

More than a decade since the start of the longest ocean warming event ever recorded, scientists are still working to understand the extent of its impacts. This unprecedented heat wave, nicknamed “The Blob,” stretched thousands of kilometres over North America’s western coastal waters, affecting everything from the smallest plankton to the largest marine mammals.

Between 2014 and 2016, when this heat wave occurred, water temperatures soared between two to six degrees C above average.

One would be forgiven for thinking this is no big deal. After all, temperatures fluctuate more than this on land most days. But not so in the ocean, where temperatures are normally much more stable because of the enormous amount of energy it takes to change them.

Although the duration of this multi-year warming event made it the first of its kind, it offers a glimpse into a future with climate change, where heat waves like this will be more frequent.

In our newly published systematic review, we synthesized the findings from 331 scientific studies documenting the ecological impacts of this marine heat wave across ecosystems, all the way from Alaska to Baja California.

Our results offer a stark warning for how profoundly ocean life can be upended by heat waves that are now a dominant signature of climate change.

(Jennifer McHenry)

Species on the move

One of the most common responses to this extreme event was that marine species moved into places where they are not normally found as they searched for cooler water. Most headed north.

In total, we identified 240 species that were found outside of their normal ranges. More than 100 of these were found further north than they had ever been recorded before, with some moving up to 1,000 kilometres.

These species on the move included everything from fish and invertebrates to seabirds and marine mammals. But species don’t all have the same discomfort level with warm water, and some species are more mobile than others. So, marine communities didn’t simply pick up and move together to avoid the heat.

Instead, marine heat waves like this one are causing a massive reorganization of ocean life, as new predators, prey and competitors intermingle for the first time. The newcomers have the potential to alter food webs and displace local species with far-reaching consequences.

(Dirk Dallas), CC BY-NC

Heatwave effects on linked species and fisheries

One of the key lessons from this heat wave is that impacts on one species can have effects that ripple throughout entire ecosystems. For example, the shifting availability of key forage fish like anchovies and sardines contributed to mass die-offs of starving seabirds and whales.

Warm, nutrient-poor waters also triggered unprecedented blooms of toxic algae. This led to the closure of Dungeness crab fisheries on the West Coast that cost local economies tens of millions of dollars.

Widespread ecological disruption

The marine heat wave also transformed coastal habitats, including kelp forests and seagrass beds. Kelp forests, sometimes called rainforests of the sea, were impacted along several thousand kilometres of coastline.

In some cases, local extinctions of these habitats have persisted for years following the event, with sustained impacts on the critters that rely on them. We still don’t know whether these changes represent permanent losses or whether any of these ecosystems will be able to recover.

(Shorezone/Samuel Starko)

Read more:

Why some of British Columbia’s kelp forests are in more danger than others

Diseases flourished in the warmer waters. The previously abundant sunflower sea star was hit particularly hard. Warmer waters likely increased the susceptibility of this species to an ongoing epidemic. This led to losses severe enough to have it listed as a critically endangered species.

Similarly, increases in seagrass disease contributed to declines in the health and abundance of the habitats these plants create.

(NOAA Fisheries West Coast/Janna Nicols), CC BY-NC-ND

Preparing for warmer water

Our review highlights how we are unprepared to respond to these challenges in real time.

With marine heat waves becoming more prevalent, we need to prepare for what is coming. Climate models indicate that these events will only get stronger as greenhouse gas emissions continue to warm our planet.

Global ocean temperatures have continued to rise over the decade since The Blob, with several years since being declared the hottest on record in the ocean, only to be surpassed the following year.

Actions such as restoring lost habitat or reducing additional stressors, like overfishing, may help ecosystems cope with some of these shocks. However, these benefits may be limited and offer only a temporary solution to a problem that is worsening.

Our review demonstrates how unpredictably these heat waves can unfold across marine ecosystems and how widespread their impacts can be. In the face of such drastic change, climate adaptation measures will only get us so far.

To stave off the worst impacts of heat waves driven by climate change, governments and industry must urgently reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The 2014-16 marine heat wave was a warning. The question now is whether we will listen.

![]()

Samuel Starko receives funding from the Forrest Research Foundation, the Australian Research Council and Revive & Restore. During this research project, he also received funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and Mitacs.

Julia K. Baum receives funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada. A Professor at the University of Victoria, she is affiliated with the Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre’s Kelp Rescue Initiative.

– ref. The world’s longest marine heat wave upended ocean life across the Pacific – https://theconversation.com/the-worlds-longest-marine-heat-wave-upended-ocean-life-across-the-pacific-260792