Source: The Conversation – Canada – By Samuel Lloyd, PhD Candidate, Department of Psychology, University of Victoria

2025 has been a year of setbacks for Canada’s climate policy. In November, the federal and Alberta governments signed a memorandum of understanding to remove strict climate policies in the province and to support the construction of a new pipeline from Alberta to northern British Columbia.

The government also cancelled the federal carbon tax this year, while ending funding for home energy-efficiency programs and delaying sales mandates for zero-emission vehicles.

These steps have pushed Canada even further from meeting its climate goals, which were already too weak to limit global warming to 1.5 C, as outlined in the Paris Climate Agreement.

What’s behind these changes and why is Canadian progress on tackling climate change so slow? Put simply, it’s because climate action threatens the profits of the fossil-fuel industry, and they’ve spent the past 50 years doing everything they can to prevent it.

While the industry has used many tools in this endeavour, perhaps its most effective has been its propaganda machine — a global network of foundations, think tanks and lobbyists known as the Climate Change Counter Movement.

In our newly published study, we review the academic and non-academic literature to map how this movement has used its influence to delay climate action in Canada.

Read more:

Why Mark Carney’s pipeline deal with Alberta puts the Canadian federation in jeopardy

The Climate Change Counter Movement

For years, the movement’s main strategy was to deny that climate change was happening or to claim that humans weren’t causing it. However, as summers got hotter and wildfires, floods and hurricanes became increasingly common, this narrative became less convincing.

The propaganda machine then adopted a new tactic. Rather than denying climate science, it exploited legitimate debates about how climate policy should be designed to sow confusion, cause political deadlock and suggest policies that don’t threaten their profits.

Three examples of these new narratives are particularly widespread in Canada: fossil-fuel solutionism (that fossil fuels can be part of efforts to tackle climate change), “whataboutism” and appeals to well-being.

Together, they uphold the claim that fossil fuels are a necessary and unavoidable part of everyday life and that Canadian fossil fuels are less carbon-heavy than those produced in the rest of the world, meaning that supporting the Canadian fossil-fuel industry would supposedly reduce greenhouse-gas emissions.

These arguments are logically flawed — fossil fuels are incompatible with a world below 1.5 C warming. They’re also based on a falsehood, because oil from the Canadian oilsands is roughly 21 per cent more polluting than conventional crude oil.

Another common argument is that fossil fuels are essential to the Canadian economy, but this narrative overstates the costs of transitioning away from fossil fuels and understates the enormous costs of allowing climate change to continue unmitigated.

While these narratives do originate from elite members of the Climate Change Counter Movement, our case study found evidence that they’re already being repeated by members of the general public and might even explain why many Canadians falsely believe that a clean energy future could include fossil fuels.

How can we tackle false fossil-fuel narratives?

1. Know ourselves

If we want to challenge false narratives about fossil fuels, we should begin by reflecting on how the Climate Change Counter Movement might have affected us already. Fossil-fuel propaganda is everywhere, and it’s hard to avoid internalizing some of it. It’s also important to consider whether challenging the fossil-fuel industry might expose us to physical or financial danger before taking action.

2. Know our enemy

Next, it’s important for us to learn as much as we can about the Climate Change Counter Movement. Who are its members? What propaganda are they spreading, and where are they spreading it? Which narratives work and which don’t? Answering these questions will be the work of academics, journalists and citizen researchers, who can take cues from efforts like the Corporate Mapping Project in their approach.

3. Target them directly

Once we have that information, we can use it to hold the fossil-fuel industry legally (and thus financially) accountable for their role in delaying climate action. Examples of these kinds of lawsuits are appearing all over the world, including in Canada where the Sue Big Oil campaign is uniting B.C. municipalities in suing fossil-fuel companies for their role in the escalating costs of climate change.

These campaigns not only discourage future meddling, but also move funds directly from the fossil-fuel industry to the communities they’ve affected, allowing them to build their own defences against future attacks.

4. Heal our wounds

However, even if lawsuits successfully discourage future activity by the Climate Change Counter Movement, we’ll still need to undo the damage they’ve already done to our society. Their efforts have left the public polarized, untrusting of governments, confused about fact versus fiction and feeling hopeless. We must reinvest in our communities and heal these societal wounds. Climate assemblies, an approach to government which emphasizes public engagement, offer a promising pathway towards many of these goals.

5. Pick our battles

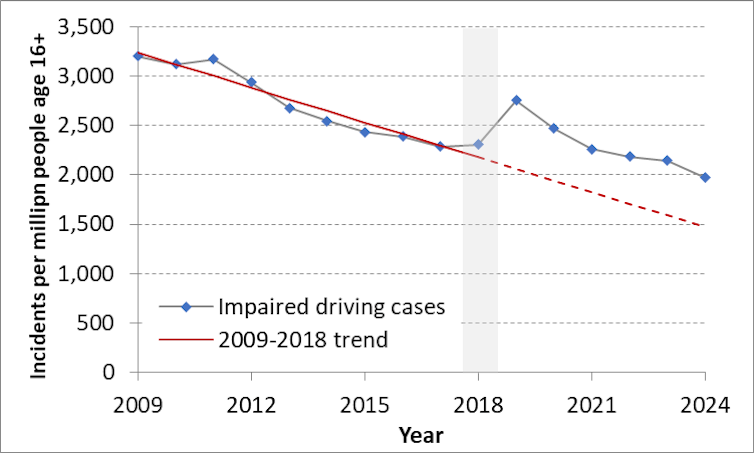

It’s also vital for governments to continue advancing climate action, even when public appetites have been damaged by propaganda campaigns. They can do this by strengthening policies that are relatively unknown, yet still effective and popular.

These policies have not been exposed to the same levels of propaganda as others like the carbon tax and are therefore still popular, while also being effective enough to account for the majority of emission reductions in Canada, the United Kingdom and California.

6. Challenge the structural roots of their power

Finally, we need to remove the root of the fossil-fuel industry’s economic and cultural power. Within our current economic system, this means redirecting financial flows away from the industry by removing fossil-fuel subsidies and implementing stringent compulsory policies to realign markets with climate goals.

The Climate Change Counter Movement is several steps ahead of us, but it hasn’t won yet. If climate change is to be stopped, we have to stop ignoring the elephant in the room and unite against the fossil-fuel industry.

![]()

Samuel Lloyd received funding from the Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions for the research project that inspired the research in this article. He wrote that paper while receiving funding from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund as part of the University of Victoria-led Accelerating Community Energy Transformation Initiative.

Katya Rhodes receives funding from Canada First Research Excellence Fund as part of the University of Victoria-led Accelerating Community Energy Transformation Initiative.

– ref. Fossil-fuel propaganda is stalling climate action. Here’s what we can do about it. – https://theconversation.com/fossil-fuel-propaganda-is-stalling-climate-action-heres-what-we-can-do-about-it-272227