Source: The Conversation – Canada – By Michael Slipenkyj, Postdoctoral Fellow, Math Lab, Department of Cognitive Science, Carleton University

Ontario’s 2024-25 Education Quality and Accountability Office (EQAO) standardized test results were recently released, and almost half (49 per cent) of Grade 6 students in English-language schools didn’t meet the provincial standard in mathematics.

These unsatisfactory results should not come as a surprise, and they cannot be attributed to lost time during COVID-19.

Ontario students have been struggling in math for many years. For instance, in 2018-19 and 2015-16, respectively, 52 per cent and 50 per cent of Grade 6 students failed to meet the provincial standard. What can be done to change this situation?

Setting stronger foundations in early math

We know from research in mathematical cognition that children’s early number knowledge (for example, at four-and-a-half years old) predicts their mathematical achievement later in school.

Read more:

New research shows quality early childhood education reduces need for later special ed

Because later learned skills build on earlier ones, kids who fall behind early may never catch up. Just as children need to get comfortable putting their face in the water before they can learn the front crawl, they need to become proficient with counting before they can learn addition and subtraction.

The best ways to support math learning are to:

-

Provide lessons with clear skill progressions;

-

Conduct regular assessments so teachers know what their students are learning; and

-

Ensure that students get plenty of targeted practice on skills they have not yet mastered.

We should equip our students with solid foundational numeracy skills in the early years and check that they are on track before the first EQAO tests in Grade 3.

Roots of the problem, solutions

Clearly, policy initiatives like the $60 million “renewed math strategy”, making new teachers pass a math test and the “back to the basics” math curriculum, have done little to improve low math achievement.

(Allison Shelley/The Verbatim Agency for EDUimages), CC BY-NC

After the 2024-25 results were announced, the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario released a statement calling for EQAO funding to be redirected to classrooms, saying “EQAO assessments shift accountability from the government’s chronic underfunding of public education to educators.”

The province agrees that math scores are too low. In the aftermath of the results release, Ontario Education Minister Paul Calandra held a news conference to say the results weren’t “good enough.” He announced the formation of a two-person advisory committee to review the situation and provide “practical recommendations that we can put into action.”

Early universal numeracy screening

As researchers studying mathematical cognition and learning, we have an evidence-based recommendation to help improve children’s math scores: schools should use universal screening to identify and track students’ numeracy learning much earlier than Grade 3 (when the first EQAO tests are given).

Screeners that assess foundational numeracy skills and other forms of assessment are critical for evaluating gaps in students’ numerical knowledge and providing them with targeted supports before they start to fall behind.

Instead of waiting for provincial results at the end of Grade 3 to identify struggling learners, we need to equip students with necessary skills and knowledge earlier.

Measuring foundational skills is critical for mathematics because more advanced skills like geometry, algebra, calculus require students to have fluent access to foundational knowledge. For example, fluent division skills support converting fractions to decimals (for instance, one quarter equals 0.25).

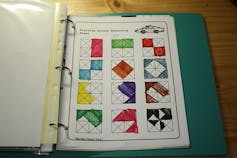

(Jimmie Quick/Flickr), CC BY

Extensive store of knowledge needed

Children who lack foundational skills will continue to struggle across grades as the expectations become more advanced. Research has found that kindergarteners with lower counting skills are more likely to under-perform in math in Grade 7. These basic skills have also been linked to other metrics of academic success.

For example, children with strong foundational numerical skills are more likely to take advanced math classes in high school or pursue post-secondary education. Importantly, students who acquire foundational skills also develop more confidence in their mathematics abilities and are less likely to develop math anxiety.

By Grade 6, students need to have acquired a rich and extensive store of knowledge for learning the more complex math required in later grades.

(Bindaas Madhavi/Flickr), CC BY-NC

The right to calculate

Human rights commissions have called for changes in education to ensure the “right to read” is protected for all students, including those with reading disabilities. We believe all students also have a right to high-quality math instruction — the right to calculate.

In efforts to connect math researchers and educators, we established the Assessment and Instruction for Mathematics (AIM) Collective. The AIM Collective is a community of researchers and educators, from universities and school districts across the country, committed to improving early math education in Canada.

Universal screening is one of the topics that AIM members have discussed in depth, because teachers often have mixed reactions to policies on screening.

However, educators we’ve partnered with have found that early math screening is a helpful teaching tool that helps educators target instruction to support children’s math learning.

Reaching full potential in math

Alberta now mandates universal numeracy screening. The Math Lab at Carleton University, where we are engaged in research, was involved in constructing grade-specific numeracy screeners for students in kindergarten to Grade 3 now in use in Alberta as well as other provinces.

Universal literacy screening is already mandated for students in Ontario from senior kindergarten to Grade 2. Initiating early universal numeracy screening is one step towards ensuring Ontario students reach their full potential in math.

Critically, screening must be accompanied by targeted support. Helping students reach their full math potential will contribute to a thriving Ontario.

As such, we call on the government to invest more in numeracy screening and earlier educational supports for struggling students.

![]()

Michael Slipenkyj is partly supported by a Mitacs internship with Vretta Inc., a Canadian educational technology company.

Heather P. Douglas has developed an early numeracy screener that is being used in four provinces in Canada. She collaborates with Vretta Inc., an educational technology company on a project to develop a digital version of the early numeracy screener. The project is funded by a Micas Accelerate grant.

Jo-Anne LeFevre has developed an early numeracy screener that is being used in four provinces in Canada. She collaborates with Vretta Inc., an educational technology company on a project to develop a digital version of the early numeracy screener, funded a Mitacs Accelerate grant.

Rebecca Merkley collaborates with Vretta Inc., a Canadian educational technology company. The project is funded by a Mitacs Accelerate grant titled: “A Research-Driven Approach to Assessment in Early Math Education”.

– ref. Increasing math scores: Why Ontario needs early numeracy screening – https://theconversation.com/increasing-math-scores-why-ontario-needs-early-numeracy-screening-273339