Source: The Conversation – in French – By Purificación López García, Directrice de recherche CNRS, Université Paris-Saclay

Entrée à l’Académie des sciences en janvier 2025, Purificación López García s’intéresse à l’origine et aux grandes diversifications du vivant sur Terre. Elle étudie la diversité, l’écologie et l’évolution des microorganismes des trois domaines du vivant (archées, bactéries, eucaryotes). Avec David Moreira, elle a émis une hypothèse novatrice pour expliquer l’origine de la cellule eucaryote, celle dont sont composés les plantes, les animaux et les champignons, entre autres. Elle est directrice de recherche au CNRS depuis 2007 au sein de l’unité Écologie- Société-Évolution de l’Université Paris-Saclay et a été récompensée de la médaille d’argent du CNRS en 2017. Elle a raconté son parcours et ses découvertes à Benoît Tonson, chef de rubrique Science et Technologie.

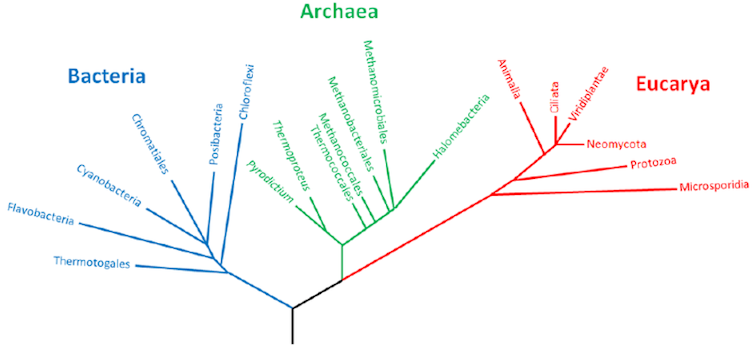

The Conversation : Vous vous intéressez à l’origine du vivant. Vivant, que l’on classifie en trois grands domaines : les eucaryotes, des organismes dont les cellules ont un noyau, comme les humains ou les plantes par exemple ; les bactéries, qui ne possèdent pas de noyau, et un troisième, sans doute le moins connu, les archées. Pouvez-vous nous les présenter ?

Purificación López García : Ce domaine du vivant a été mis en évidence par Carl Woese à la fin des années 1970. Quand j’ai commencé mes études, à la fin des années 1980, cette découverte ne faisait pas consensus, il y avait encore beaucoup de résistance de la part de certains biologistes à accepter un troisième domaine du vivant. Ils pensaient qu’il s’agissait tout simplement de bactéries. En effet, comme les bactéries, les archées sont unicellulaires et n’ont pas de noyau. Il a fallu étudier leurs gènes et leurs génomes pour montrer que les archées et les bactéries étaient très différentes entre elles et même que les archées étaient plus proches des eucaryotes que des bactéries au niveau de leur biologie moléculaire.

Comment Carl Woese a-t-il pu classifier le vivant dans ces trois domaines ?

P. L. G. : On est donc à la fin des années 1970. C’est l’époque où commence à se développer la phylogénie moléculaire. L’idée fondatrice de cette discipline est qu’il est possible d’extraire des informations évolutives à partir des gènes et des protéines codées dans le génome de tous les êtres vivants. Certains gènes sont conservés chez tous les organismes parce qu’ils codent des ARN ou des protéines dont la fonction est essentielle à la cellule. Toutefois, la séquence en acides nucléiques (les lettres qui composent l’ADN : A, T, C et G ; U à la place de T dans l’ARN) et donc celle des acides aminés des protéines qu’ils codent (des combinaisons de 20 lettres) va varier. En comparant ces séquences, on peut déterminer si un organisme est plus ou moins proche d’un autre et classifier l’ensemble des organismes en fonction de leur degré de parenté évolutive.

Carl Woese est le premier à utiliser cette approche pour classifier l’ensemble du vivant : de la bactérie à l’éléphant, en passant par les champignons… Il va s’intéresser dans un premier temps non pas à l’ADN mais à l’ARN et, plus précisément, à l’ARN ribosomique. Le ribosome est la structure qui assure la traduction de l’ARN en protéines. On peut considérer que cette structure est la plus conservée dans tout le vivant : elle est présente dans toutes les cellules.

CC BY

Avec ses comparaisons des séquences d’ARN ribosomiques, Woese montre deux choses : que l’on peut établir un arbre universel du vivant en utilisant des séquences moléculaire et qu’un groupe de séquences d’organismes considérés comme de bactéries « un peu bizarres », souvent associées à des milieux extrêmes, forment une clade (un groupe d’organismes) bien à part. En étudiant leur biologie moléculaire et, plus tard, leurs génomes, les archées s’avéreront en réalité beaucoup plus proches des eucaryotes, tout en ayant des caractéristiques propres, comme la composition unique des lipides de leurs membranes.

Aujourd’hui, avec les progrès des méthodes moléculaires, cette classification en trois grands domaines reste d’actualité et est acceptée par l’ensemble de la communauté scientifique. On se rend compte aussi que la plupart de la biodiversité sur Terre est microbienne.

Vous vous êtes intéressée à ces trois grands domaines au fur et à mesure de votre carrière…

P. L. G. : Depuis toute petite, j’ai toujours été intéressée par la biologie. En démarrant mes études universitaires, les questions liées à l’évolution du vivant m’ont tout de suite attirée. Au départ, je pensais étudier la biologie des animaux, puis j’ai découvert la botanique et enfin le monde microbien, qui m’a complètement fascinée. Toutes les formes de vie m’intéressaient, et c’est sûrement l’une des raisons pour lesquelles je me suis orientée vers la biologie marine pendant mon master. Je pouvais travailler sur un écosystème complet pour étudier à la fois les microorganismes du plancton, mais aussi les algues et les animaux marins.

Puis, pendant ma thèse, je me suis spécialisée dans le monde microbien et plus précisément dans les archées halophiles (celles qui vivent dans des milieux très concentrés en sels). Les archées m’ont tout de suite fascinée parce que, à l’époque, on les connaissait comme des organismes qui habitaient des environnements extrêmes, très chauds, très salés, très acides. Donc, c’était des organismes qui vivaient aux limites du vivant. Les étudier, cela permet de comprendre jusqu’où peut aller la vie, comment elle peut évoluer pour coloniser tous les milieux, même les plus inhospitaliers.

Cette quête de l’évolution que j’avais toujours à l’esprit a davantage été nourrie par des études sur les archées hyperthermophiles lors de mon postdoctorat, à une époque où une partie de la communauté scientifique pensait que la vie aurait pu apparaître à proximité de sources hydrothermales sous-marines. J’ai orienté mes recherches vers l’origine et l’évolution précoce de la vie : comment est-ce que la vie est apparue et s’est diversifiée ? Comment les trois domaines du vivant ont-ils évolué ?

Pour répondre à ces questions, vous avez monté votre propre laboratoire. Avec quelle vision ?

P. L. G. : Après un bref retour en Espagne, où j’ai commencé à étudier la diversité microbienne dans le plancton océanique profond, j’ai monté une petite équipe de recherche à l’Université Paris-Sud. Nous nous sommes vraiment donné la liberté d’explorer la diversité du vivant avec les outils moléculaires disponibles, mais en adoptant une approche globale, qui prend en compte les trois domaines du vivant. Traditionnellement, les chercheurs se spécialisent : certains travaillent sur les procaryotes – archées ou bactéries –, d’autres sur les eucaryotes. Les deux mondes se croisent rarement, même si cela commence à changer.

Cette séparation crée presque deux cultures scientifiques différentes, avec leurs concepts, leurs références et même leurs langages. Pourtant, dans les communautés naturelles, cette frontière n’existe pas : les organismes interagissent en permanence. Ils échangent, collaborent, entrent en symbiose mutualiste ou, au contraire, s’engagent dans des relations de parasitisme ou de compétition.

Nous avons décidé de travailler simultanément sur les procaryotes et les eucaryotes, en nous appuyant d’abord sur l’exploration de la diversité. Cette étape est essentielle, car elle constitue la base qui permet ensuite de poser des questions d’écologie et d’évolution.

L’écologie s’intéresse aux relations entre organismes dans un écosystème donné. Mais mes interrogations les plus profondes restent largement des questions d’évolution. Et l’écologie est indispensable pour comprendre ces processus évolutifs : elle détermine les forces sélectives et les interactions quotidiennes qui façonnent les trajectoires évolutives, en favorisant certaines tendances plutôt que d’autres. Pour moi, les deux dimensions – écologique et évolutive – sont intimement liées, surtout dans le monde microbien.

Sur quels terrains avez-vous travaillé ?

P. L. G. : Pour approfondir ces questions, j’ai commencé à travailler dans des environnements extrêmes, des lacs de cratère mexicains au lac Baïkal en Sibérie, du désert de l’Atacama et l’Altiplano dans les Andes à la dépression du Danakil en Éthiopie, et en m’intéressant en particulier aux tapis microbiens. À mes yeux, ces écosystèmes microbiens sont les véritables forêts du passé. Ce type de systèmes a dominé la planète pendant l’essentiel de son histoire.

Ana Gutiérrez-Preciado, Fourni par l’auteur

La vie sur Terre est apparue il y a environ 4 milliards d’années, alors que notre planète en a environ 4,6. Les eucaryotes, eux, n’apparaissent qu’il y a environ 2 milliards d’années. Les animaux et les plantes ne se sont diversifiés qu’il y a environ 500 millions d’années : autant dire avant-hier à l’échelle de la planète.

Pendant toute la période qui précède l’émergence des organismes multicellulaires complexes, le monde était entièrement microbien. Les tapis microbiens, constitués de communautés denses et structurées, plus ou moins épaisses, formaient alors des écosystèmes très sophistiqués. Ils étaient, en quelque sorte, les grandes forêts primitives de la Terre.

Étudier aujourd’hui la diversité, les interactions et le métabolisme au sein de ces communautés – qui sont devenues plus rares car elles sont désormais en concurrence avec les plantes et les animaux – permet de remonter le fil de l’histoire évolutive. Ces systèmes nous renseignent sur les forces de sélection qui ont façonné la vie dans le passé ainsi que sur les types d’interactions qui ont existé au cours des premières étapes de l’évolution.

Certaines de ces interactions ont d’ailleurs conduit à des événements évolutifs majeurs, comme l’origine des eucaryotes, issue d’une symbiose entre procaryotes.

Comment ce que l’on observe aujourd’hui peut-il nous fournir des informations sur le passé alors que tout le vivant ne cesse d’évoluer ?

P. L. G. : On peut utiliser les communautés microbiennes actuelles comme des analogues de communautés passées. Les organismes ont évidemment évolué – ils ne sont plus les mêmes –, mais nous savons deux choses essentielles. D’abord, les fonctions centrales du métabolisme sont bien plus conservées que les organismes qui les portent. En quelque sorte, il existe un noyau de fonctions fondamentales. Par exemple, il n’existe que très peu de manières de fixer le CO₂ présent dans l’atmosphère. La plus connue est le cycle de Calvin associé à la photosynthèse oxygénique de cyanobactéries des algues et des plantes. Ce processus permet d’utiliser le carbone du CO₂ pour produire des molécules organiques plus ou moins complexes indispensables à tout organisme.

On connaît six ou sept grandes voies métaboliques de fixation du carbone inorganique, qui sont en réalité des variantes les unes des autres. La fixation du CO₂, c’est un processus absolument central pour tout écosystème. Certains organismes, dont les organismes photosynthétiques, fixent le carbone. Ce sont les producteurs primaires.

Ensuite vient toute la diversification d’organismes et des voies qui permettent de dégrader et d’utiliser cette matière organique produite par les fixateurs de carbone. Et là encore, ce sont majoritairement les microorganismes qui assurent ces fonctions. Sur Terre, ce sont eux qui pilotent les grands cycles biogéochimiques. Pas tellement les plantes ou les animaux. Ces cycles existaient avant notre arrivée sur la planète, et nous, animaux comme plantes, ne savons finalement pas faire grand-chose à côté de la diversité métabolique microbienne.

Les procaryotes – archées et bactéries – possèdent une diversité métabolique bien plus vaste que celle des animaux ou des végétaux. Prenez la photosynthèse : elle est héritée d’un certain type de bactéries que l’on appelle cyanobactéries. Ce sont elles, et elles seules, chez qui la photosynthèse oxygénique est apparue et a évolué (d’autres bactéries savent faire d’autres types de photosynthèse dites anoxygéniques). Et cette innovation a été déterminante pour notre planète : avant l’apparition des cyanobactéries, l’atmosphère ne contenait pas d’oxygène. L’oxygène atmosphérique actuel n’est rien d’autre que le résultat de l’accumulation d’un déchet de cette photosynthèse.

Les plantes et les algues eucaryotes, elles, n’ont fait qu’hériter de cette capacité grâce à l’absorption d’une ancienne cyanobactérie capable de faire la photosynthèse (on parle d’endosymbiose). Cet épisode a profondément marqué l’évolution des eucaryotes, puisqu’il a donné naissance à toutes les lignées photosynthétiques – algues et plantes.

À l’instar de la fixation du carbone lors de la photosynthèse, ces voies métaboliques centrales sont beaucoup plus conservées que les organismes qui les portent. Ces organismes, eux, évoluent en permanence, parfois très rapidement, pour s’adapter aux variations de température, de pression, aux prédateurs, aux virus… Pourtant, malgré ces changements, les fonctions métaboliques centrales restent préservées.

Et ça, on peut le mesurer. Lorsque l’on analyse la diversité microbienne dans une grande variété d’écosystèmes, on observe une diversité taxonomique très forte, avec des différences d’un site à l’autre. Mais quand on regarde les fonctions de ces communautés, de grands blocs de conservation apparaissent. En appliquant cette logique, on peut donc remonter vers le passé et identifier des fonctions qui étaient déjà conservées au tout début de la vie – des fonctions véritablement ancestrales. C’est un peu ça, l’idée sous-jacente.

Finalement, jusqu’où peut-on remonter ?

P. L. G. : On peut remonter jusqu’à un organisme disons « idéal » que l’on appelle le Last Universal Common Ancestor, ou LUCA – le dernier ancêtre commun universel des organismes unicellulaires. Mais on sait que cet organisme était déjà très complexe, ce qui implique qu’il a forcément été précédé d’organismes beaucoup plus simples.

On infère l’existence et les caractéristiques de cet ancêtre par comparaison : par la phylogénie moléculaire, par l’étude des contenus en gènes et des propriétés associées aux trois grands domaines du vivant. En réalité, je raisonne surtout en termes de deux grands domaines, puisque l’on sait aujourd’hui que les eucaryotes dérivent d’une symbiose impliquant archées et bactéries. Le dernier ancêtre commun, dans ce cadre, correspondrait donc au point de bifurcation entre les archées et les bactéries.

À partir de là, on peut établir des phylogénies, construire des arbres, et comparer les éléments conservés entre ces deux grands domaines procaryotes. On peut ainsi inférer le « dénominateur commun », celui qui devait être présent chez cet ancêtre, qui était probablement déjà assez complexe. Les estimations actuelles évoquent un génome comprenant peut-être entre 2 000 et 4 000 gènes.

Cela nous ramène à environ 4 milliards d’années. Vers 4,4 milliards d’années, on commence à voir apparaître des océans d’eau liquide et les tout premiers continents. C’est à partir de cette période que l’on peut vraiment imaginer le développement de la vie. On ne sait pas quand exactement, mais disons qu’autour de 4-4,2 milliards d’années, c’est plausible. Et on sait que, à 3,5 milliards d’années, on a déjà des fossiles divers de tapis microbiens primitifs (des stromatolites fossiles).

Et concernant notre groupe, les eucaryotes, comment sommes-nous apparus ?

P. L. G. : Nous avons proposé une hypothèse originale en 1998 : celle de la syntrophie. Pour bien la comprendre, il faut revenir un peu sur l’histoire des sciences, notamment dans les années 1960, quand Lynn Margulis, microbiologiste américaine, avance la théorie endosymbiotique. Elle propose alors que les chloroplastes des plantes et des algues – les organites qui permettent de réaliser la photosynthèse dans les cellules de plantes – dérivent d’anciennes bactéries, en particulier de cyanobactéries, qu’on appelait à l’époque « algues vert-bleu ». Et elle avance aussi que les mitochondries, l’organite eucaryote où se déroule la respiration et qui nous fournit notre énergie, proviennent elles aussi d’anciennes bactéries endosymbiotes – un endosymbiote étant un organisme qui vit à l’intérieur des cellules d’un autre.

Ces idées, qui avaient été déjà énoncées au début du vingtième siècle et que Margulis a fait revivre, ont été très débattues. Mais à la fin des années 1970, avec les premiers arbres phylogénétiques, on a pu démontrer que mitochondries et chloroplastes dérivent effectivement d’anciennes bactéries endosymbiotes : les cyanobactéries pour les chloroplastes, et un groupe que l’on appelait autrefois les « bactéries pourpres » pour les mitochondries.

L’hypothèse dominante, à cette époque, pour expliquer l’origine des eucaryotes, repose sur un scénario dans lequel un dernier ancêtre commun se diversifie en trois grands groupes ou domaines : les bactéries, les archées et les eucaryotes. Les archées sont alors vues comme le groupe-frère des eucaryotes, avec une biologie moléculaire et des protéines conservées qui se ressemblent beaucoup. Dans ce modèle, la lignée proto-eucaryote qui conduira aux eucaryotes et qui développe toutes les caractéristiques des eucaryotes, dont le noyau, acquiert assez tardivement la mitochondrie via l’endosymbiose d’une bactérie, ce qui lancerait la diversification des eucaryotes.

Sauf que, dans les années 1990, on commence à se rendre compte que tous les eucaryotes possèdent ou ont possédé des mitochondries. Certains groupes semblaient en être dépourvus, mais on découvre qu’ils les ont eues, que ces mitochondries ont parfois été extrêmement réduites ou ont transféré leurs gènes au noyau. Cela signifie que l’ancêtre de tous les eucaryotes avait déjà une mitochondrie. On n’a donc aucune preuve qu’une lignée « proto-eucaryote » sans mitochondrie ait jamais existé.

C’est dans ce contexte que de nouveaux modèles fondés sur la symbiose émergent. On savait déjà que les archées et les eucaryotes partageaient des similarités importantes en termes de protéines impliquées dans des processus informationnels (réplication de l’ADN, transcription, traduction de l’ARN aux protéines). Nous avons proposé un modèle impliquant trois partenaires : une bactérie hôte (appartenant aux deltaprotéobactéries), qui englobe une archée prise comme endosymbionte, cette archée devenant le futur noyau. Les gènes eucaryotes associés au noyau seraient ainsi d’origine archéenne.

Puis une seconde endosymbiose aurait eu lieu, avec l’acquisition d’une autre bactérie (une alphaprotéobactérie) : l’ancêtre de la mitochondrie, installée au sein de la bactérie hôte.

Toutefois, à l’époque, ces modèles fondés sur la symbiose n’étaient pas considérés très sérieusement. La donne a changé avec la découverte, il y a une dizaine d’années, d’un groupe particulier d’archées, appelées Asgard, qui partagent beaucoup de gènes avec les eucaryotes, qui sont en plus très similaires. Les arbres phylogénétiques faits avec des protéines très conservées placent les eucaryotes au sein de ces archées. Cela veut dire que les eucaryotes ont une origine symbiogénétique : ils dérivent d’une fusion symbiotique impliquant au minimum une archée (de type Asgard) et une alpha-protéobactérie, l’ancêtre de la mitochondrie. Mais la contribution d’autres bactéries, notamment des deltaprotéobactéries, des bactéries sulfato-réductrices avec lesquelles les archées Asgard établissent des symbioses syntrophiques dans l’environnement, n’est pas exclue.

Aujourd’hui, l’eucaryogénèse est un sujet étudié activement. La découverte des archées Asgard a renforcé la vraisemblance de ce type de modèle symbiogénétique. Des chercheurs qui considéraient ces idées comme trop spéculatives – parce qu’on ne pourra jamais avoir de preuve directe d’un événement datant d’il y a 2 milliards d’années – s’y intéressent désormais. Tous ceux qui travaillent sur la biologie cellulaire des eucaryotes se posent la question, parce qu’on peut aujourd’hui remplacer certaines protéines ou homologues eucaryotes par leurs variantes Asgard… et ça fonctionne.

![]()

Purificación López García ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d’une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n’a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

– ref. D’où venons-nous ? Un voyage de 4 milliards d’années jusqu’à l’origine de nos cellules – https://theconversation.com/dou-venons-nous-un-voyage-de-4-milliards-dannees-jusqua-lorigine-de-nos-cellules-271900