Source: The Conversation – USA – By Nilton O. Rennó, Professor of Climate and Space Sciences Engineering, University of Michigan

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com.

Are there thunderstorms on Mars? – Cade, age 7, Houston, Texas

Mars is a very dry planet with very little water in its atmosphere and hardly any clouds, so you might not expect it to have storms. Yet, there is lightning and thunder on Mars – although not with rain, nor with the same gusto as weather on Earth.

More than 10 years ago, my planetary science colleagues and I found the first evidence for lightning strikes on Mars. In the following decade, other researchers have continued to study what lightning might be like on the red planet. In November 2025, a Mars rover first captured the spectacular sounds of lightning sparking on the Martian surface.

Fernando Saca, University of Michigan

Lightning on Mars

On Earth, lightning is an electric discharge that begins inside big clouds.

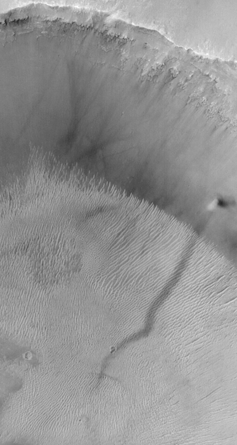

But because Mars is so dry, it doesn’t have clouds of water – instead, it has clouds of dust. With little water to weigh down dirt on Mars, dust clouds can quickly grow into huge, windy dust storms a few times taller than Earth’s tallest thunderstorms.

When smaller dust particles and larger sand particles collide with each other while being whipped around by these storms, they pick up a static charge. Smaller dust particles take on a positive charge, while larger sand particles become negative. The smaller dust particles are lighter and will float higher, while the heavier sand tends to fall closer to the ground.

Because oppositely charged particles don’t like to be apart, eventually the energy building between the negative charges higher up in the dust storm and the positive charges closer to the ground becomes too great and is released as electricity – similar to lightning.

The air around the electricity rapidly warms up and expands – on Earth, this creates the shock waves that you hear as thunder.

Nobody has seen a flash of lightning on Mars, but we suspect it’s more like the glow from a neon light rather than a powerful lightning bolt. The atmosphere near the surface of Mars is about 100 times less dense than on Earth: It’s much more similar to the air inside neon lights.

Mars Global Surveyor/NASA/JPL/Malin Space Science Systems

Releasing radio waves

Besides shock waves and visible light, lightning also produces other types of waves that the human eye can’t see: X-ray and radio waves. The ground and the top of the atmosphere both conduct electricity well, so they guide these radio waves and cause them to produce signals with specific radio frequencies. It’s kind of like how you might tune into specific radio channels for news or music, but instead of different channels, scientists can identify the radio waves coming from lightning.

While nobody has ever seen visible light from Martian lightning, we have heard something similar to the radio waves created by lightning on Earth. That’s the noise that the Perseverance rover reported at the end of 2025. They sound like electric sparks do on Earth. The rover recorded these signals on a microphone as small, sandy tornadoes passed by.

NASA/JPL-Caltech, CC BY

Searching for Martian lightning

When my colleagues and I went hunting for lightning on Mars a decade ago, we knew the red planet emitted more radio waves during dust storm seasons. So, we searched for modest increases in radio signals from Mars using the large radio dishes that NASA uses to talk to its spacecraft. The dishes function like big ears that listen for faint radio signals from spacecraft far from Earth.

We spent from five to eight hours every day listening to Mars for three weeks. Eventually, we found the signals we were looking for: radio bursts with frequencies that matched up with the radio waves that lightning on Earth can create.

Nilton Renno, University of Michigan

To find the particular source of these lightning-like signals, we searched for dust storms in pictures taken by spacecraft orbiting Mars. We matched a dust storm nearly 25 miles (40 kilometers) tall to the time when we’d heard the radio signals.

Learning about lightning on Mars helps scientists understand whether the planet could have once hosted extraterrestrial life. Lightning may have helped create life on Earth by converting molecules of nitrogen and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere into amino acids. Amino acids make up proteins, tens of thousands of which are found in a human body.

So, Mars does have storms, but they’re far drier and dustier than the thunderstorms on Earth. Scientists are continually studying lightning on Mars to better understand the geology of the red planet and its potential to host living organisms.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

![]()

Nilton O. Rennó receives funding from NASA, JPL, DARPA, and IARPA.

– ref. Are there thunderstorms on Mars? A planetary scientist explains the red planet’s dry, dusty storms – https://theconversation.com/are-there-thunderstorms-on-mars-a-planetary-scientist-explains-the-red-planets-dry-dusty-storms-271364