Source: The Conversation – USA – By Guillaume Chomicki, Professor of Evolutionary Biology, Durham University

In the middle of the South Pacific, a group of Fijian plants have solved a problem that has long puzzled scientists: How can an organism cooperate with multiple partners that are in turn competing for the same resources? The solution turns out to be simple – compartmentalization.

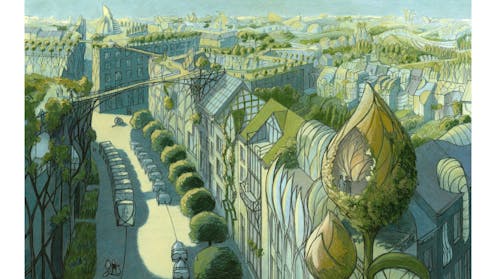

Imagine an apartment building where unfriendly neighbors might clash if they run into each other, but smart design keeps everyone peacefully separated. In our new research published in the journal Science, we show how certain plants build specialized structures that allow multiple aggressive ant species to live side by side inside them without ever meeting.

Ants and plants cooperate in Fijian rainforest

Squamellaria plants are epiphytes – meaning they don’t have roots attached to the ground, and instead grow on another plant for physical support. They live high up in the rainforest canopy, in the South Pacific.

Because they don’t have direct access to the soil’s nutrients, Squamellaria plants have evolved an original strategy to acquire what they need: In a mutually beneficial relationship, they grow structures that appeal to ants looking for a place to live. This kind of long-term relationship between species – whether helpful or harmful – is called symbiosis.

Here’s how it works in this case. The base of the Squamellaria plant stem forms a swollen, hollow structure called a domatium – a perfect place for ants to live. Domatia gradually enlarge to the size of a soccer ball, containing ever more plant-made houses ready for ants to move into. Each apartment can house a colony made up of thousands of ants.

G. Chomicki

The relationship between the ants and the plants is mutualistic, meaning both parties benefit. The ants gain a nice sturdy and private nest space, while the plants gain essential nutrients. They obtain nitrogen and phosphorus from the ants’ feces and from detritus – including dead insects, plant bits and soil – that the ants bring inside the domatium.

However, tropical rainforest canopies are battlegrounds for survival. Ants compete fiercely for nesting space, taking over any hollow branch or space under tree bark. Any Squamellaria ant house would thus be at risk of being colonized and taken over by other incoming ants, disrupting the existing partnership.

Until now, it was unclear how the cooperative relationships between ants and plants remain stable in this competitive environment.

Walls keep the peace

Our first hint about what keeps the peace in the Squamellaria real estate came when we discovered several ant species living in the same plant domatium. This finding just didn’t make sense. How could aggressively competing ant species live together?

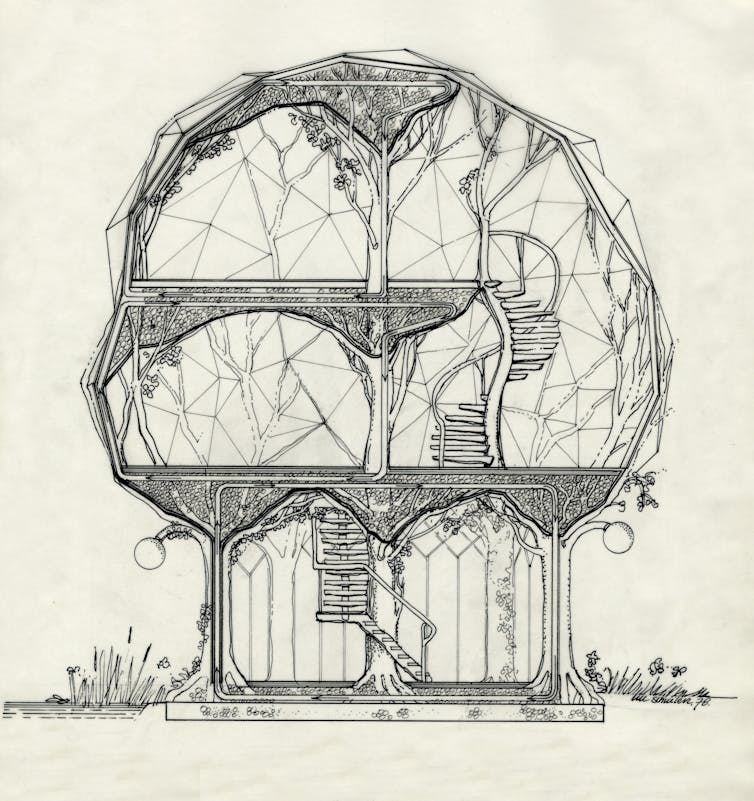

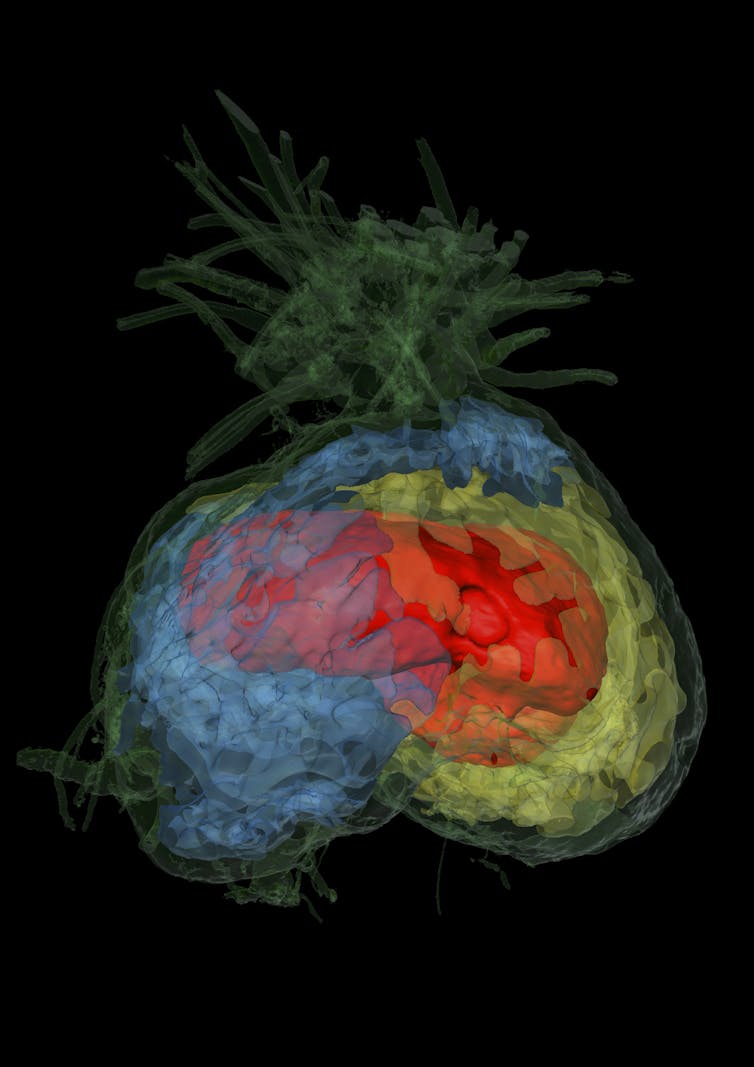

We investigated the structure of domatia using computed-tomography scanning, which revealed an interesting internal architecture. Each plant domatium is divided into distinct compartments, with thick walls isolating each unit. Independent entrances prevent direct contact between the inhabitants of different units. The walls safeguard the peace as they prevent encounters between different ant species.

S. Renner & G. Chomicki

Back in the lab, when we removed the ant apartments’ walls, placing inhabitants in contact with their neighbors, deadly fights broke out between ant species. The compartmentalized architecture is thus critical in preventing symbiont “wars” and maintaining the stability of the plant’s partnership with all the ants that call it home. By minimizing deadly conflicts that could harm the ants it hosts, this strategy ensures that the plant retains access to sufficient nutrients provided by the ants.

This research reveals a new mechanism that solves a long-standing riddle – the stability of symbioses involving multiple unrelated partners. Scientists hadn’t previously discovered aggressive animal symbionts living together inside a single plant host. Our study reveals for the first time how simple compartmentalization is a highly effective way to reduce conflict, even in the most extreme cases. The ant colonies are living side by side, but not really together.

What’s next

The key to conflict-free living of multipartner symbioses discovered in these Fijian plants – compartmentalization – is likely important in other multispecies partnerships. However, it remains unknown whether compartmentalization is widespread in nature. Research on cooperation between species has long focused on pairwise interactions. Our new insights suggest a need to reinvestigate other multispecies mutualistic symbioses to see how they maintain stability.

![]()

Guillaume Chomicki receives funding from UKRI.

Susanne S. Renner received previous funding from the German Research Foundation (DFG)

– ref. This tropical plant builds isolated ‘apartments’ to prevent battles among the aggressive ant tenants it relies on for survival – https://theconversation.com/this-tropical-plant-builds-isolated-apartments-to-prevent-battles-among-the-aggressive-ant-tenants-it-relies-on-for-survival-260674