Source: The Conversation – UK – By Travis Van Isacker, Senior Research Associate, School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies, University of Bristol

On a cold, wet November evening, Issa Mohamed Omar and more than 30 other men, women and children set off from their informal camp near the northern French port city of Dunkirk. They walked through the darkness in near-silence for around two hours, until they reached the beach from where they hoped to start a new and better life.

As they arrived, five men were busy pumping up an inflatable dinghy and attaching an outboard engine. These people smugglers had charged each of their customers more than a thousand euros for a trip that costs someone with the right passport less than a hundred.

The travellers were given life-vests, arranged into rows and counted. “There are 33 of you,” one of the smugglers said. For many on board, this was not their first attempt at reaching England.

Most came from Iraqi Kurdistan, including Kazhal Ahmed Khidir Al-Jammoor from Erbil, who was travelling with her three children: Hadiya, Mubin and Hasti Rizghar Hussein, respectively aged 22, 16 and seven.

A father and son from Egypt were shown how the engine worked and provided a GPS device and directions to Dover, around 35 miles (60km) to the west across the Channel. Mohamed Omar would later recall:

The Egyptian man was put in charge of steering the boat by the smugglers. He was travelling with his son, who looked like he was in his late teens or maybe early 20s. I do not know how they came to be the driver and navigator.

There were also at least three Ethiopian nationals – one of whom, father-of-two Fikiru Shiferaw from Addis Ababa, sent his wife Emebet at home in Ethiopia a final WhatsApp voice message:

We have already boarded the boat. We are on the way. I will turn off my phone now. Goodnight, I will call you tomorrow morning.

These were the last words she would ever receive from her husband.

What happened to Fikiru Shiferaw and the other passengers on the night of November 23-24 2021 has been the subject of the UK’s Cranston Inquiry which, during March 2025, heard from 22 witnesses to the disaster, including officers involved in the UK’s search-and-rescue (SAR) response. Chaired by former High Court judge Sir Ross Cranston, the independent inquiry also heard from Mohamed Omar from Somalia – one of only two survivors – as well as family members of many of the dead and missing.

These hearings not only shed light on the actions of UK Border Force and His Majesty’s Coastguard officers during the failed rescue operation – designated Incident Charlie – in the early hours of November 24, but the agencies’ approach to “small boat crossings” in general dating back to 2017.

According to the testimonies, officers had been operating under extreme pressure in the months leading up to the disaster. Kevin Toy, master of the Border Force ship Valiant which was sent out to search for the missing dinghy that night, explained that in the run-up to the incident, “night after night” he could see his crew were “utterly exhausted” by the end of their shifts.

The evidence shows the British government was aware of the growing risk that Border Force and HM Coastguard could be overwhelmed by the rising number of small boat crossings – and that people might die as a result. In May 2020, a document produced by the Department for Transport acknowledged that “SAR resources can be overwhelmed if current incident numbers persist”. At least three senior HM Coastguard officers identified the same risk in August 2021.

Multiple communication failures have also been exposed by the inquiry – among British officers, with their opposite numbers in France, and between both countries’ emergency services and the increasingly desperate people aboard the sinking dinghy.

Despite numerous distress calls and GPS coordinates being shared via WhatsApp, a rescue boat failed to reach the travellers in time. Amid the confusion, when their calls stopped, the coastguard assumed Charlie’s passengers had been picked up and were safe. In fact, they were perishing in the cold waters of the Channel over more than ten hours.

The Insights section is committed to high-quality longform journalism. Our editors work with academics from many different backgrounds who are tackling a wide range of societal and scientific challenges.

As part of my research into the digital transformation of the UK-France border, I attended the inquiry and have studied the many statements, call transcripts, operational logs, emails and meeting minutes it has made public. Initially, I wanted to understand how the November 2021 disaster became a watershed moment in the UK government’s response to people trying to cross the Channel by small boat or dinghy, catalysing the transformation of the UK’s maritime border into the hyper-surveilled space it is today.

But, after speaking to representatives for Mohamed Omar and the bereaved families as well as migrant rights organisations, larger questions have emerged. In particular, given the inquiry’s singular focus on this one catastrophic event in November 2021, those I spoke to are concerned that its recommendations will be unable to prevent further deaths from occurring in the Channel, which have risen dramatically over the last 18 months.

How ‘small boat crossings’ began

Since the UK and France began operating “juxtaposed” border controls in the early 1990s (meaning border checks occur before departure), asylum seekers trying to reach England have had to make irregular journeys across the Channel. Until 2018, these were typically aboard trains and ferries – after sneaking on to a lorry or through a French port’s perimeter security.

At the time of the “Jungle” camp near Calais in 2015-16, media coverage of collective attempts by its residents to enter French ports spiked UK government investment in the border. Between 2014 and 2018, it gave its French counterpart at least £123 million to “strengthen the border and maintain juxtaposed controls”. These funds paid for French police to patrol the ports and border cities, regularly evict migrants’ living sites, and finance detention and relocation centres.

As admitted by then-home secretary Sajid Javid in 2019, this increased security led people to find other ways across the Channel. Beginning in the winter of 2018, smugglers organised journeys in small, seaworthy vessels they had stolen from marinas along the French coast. These “small boats” continue to lend their name to this migration phenomenon – yet the unseaworthy inflatable dinghies used today, with no keel or rigid hull, are not worthy of the name.

Even in the context of the usual sensationalism surrounding irregular migration to the UK, small boat journeys were met with an especially intense response, both politically and in the media.

When 101 people crossed between Christmas and New Year in 2018, Javid declared it a major incident. Ever since, “stopping the boats” has been one of the UK government’s highest priorities. Despite small boat arrivals making up only 29% of UK asylum claimants in 2018-24, billions of pounds have been spent to try and control the route.

Frosty relations and the ‘pushback’ plan

As Channel crossings rose sharply over 2020-21, worsening relations between France and the UK due to Brexit complicated how the two governments worked together to respond. In his testimony, former clandestine Channel threat commander Dan O’Mahoney – appointed by Javid’s successor, Priti Patel, to “make small boat crossings unviable” – described relations between the two countries as already “very frosty” when he began in August 2020.

After France’s then-interior minister, Gérald Darmanin, axed a plan for UK vessels to take rescued migrants back to Dunkirk, O’Mahoney was tasked by senior ministers to come up with an alternative. The resulting “pushback” plan, called Operation Sommen, involved Border Force officers on jet skis driving into migrant dinghies to turn them back as they crossed the border line into UK waters. When France learned of the plan, O’Mahoney recalled:

They thought it went counter to their and our obligations around safety of life at sea … They objected to it very strongly, and it affected our already quite strained relationship with them further.

Operation Sommen was abandoned in April 2022 before having ever been used in anger. However, preparations were said to have taken up “a very considerable amount of time and resource” at both the Home Office and the Maritime and Coastguard Agency – and had “a detrimental effect” on the UK’s overall SAR response to small boat crossings.

At a meeting of senior officials in June 2021 to discuss Operation Sommen, ministers had made clear that the “numbers of people crossing [was] a political problem” – and that improving SAR capabilities did not “fit with [the] narrative of taking back control of borders”.

Although senior HM Coastguard officers recognised “it is extremely difficult to locate small boats or communicate with those onboard”, the inquiry heard that officers did not recall receiving “any small boat training before November 2021”, other than in the procedure to allow Border Force to push them back to French waters.

The head of Border Force’s Maritime Command, Stephen Whitton, told the inquiry he was under “a huge amount of pressure” to prevent small boat crossings, while also “providing the bulk of the support to search and rescue”. Despite carrying out 90% of all small boat rescues in the Channel and “regularly being overwhelmed”, Border Force Maritime Command received “no additional assets to manage the search and rescue response” before November 2021.

‘The pressure we were under’

When the decision was taken for Border Force – a law enforcement rather than search-and-rescue organisation – to be the primary responders to small boat crossings in 2018, only around 100 people were crossing each month. Yet by the time of the disaster three years later, according to an internal Home Office document, the total for 2021 was “already more than 25,000”.

At the inquiry, O’Mahoney stated: “As 2021 went on, it became much clearer that … frankly, we just needed more [rescue] boats.” Whitton admitted that before the disaster, Border Force, HM Coastguard, the Royal National Lifeboat Institution and other support organisations were all “on our knees in terms of the pressure we were under, and it was getting hugely challenging”.

The evidence shows this pressure was acutely felt inside Dover’s Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre, which sits atop the port’s famous white cliffs offering a commanding view of the Channel. Inside, Coastguard officers coordinate SAR operations and control vessel traffic in the Dover Strait – one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes.

On the night of November 23-24, three coastguard officers were on search-and-rescue duty: team leader Neal Gibson, maritime operations officer Stuart Downs, and a trainee – unnamed by the inquiry – who was officially only present as an observer.

Travis Van Isacker, CC BY-NC-SA

Staffing appears to have been a longstanding issue at the Dover coastguard station where, according to divisional commander Mike Bill, there was “poor retention of staff” and “experience and competence weren’t the best”. Only the day before the disaster, during a migrant red days meeting – convened when, due to good weather, the probability of Channel crossers is considered “highly likely” – chief coastguard Peter Mizen had warned that only having two qualified officers at Dover on nights “isn’t enough”.

Over recent months, as the station had become busier responding to small boat crossings and in the wake of an unsuccessful recruitment drive, staff were having to work flat-out throughout their shifts, and were being asked to come in on scheduled days off.

On the night of November 23-24, owing to staff shortages, team leader Gibson told the inquiry he had to cover traffic control duties for three hours from 10.30pm. This meant he was away from the SAR desk at 00.41am, when a message arrived from the national rescue coordination centre along the coast in Fareham, stating that the Coastguard’s scheduled surveillance aeroplanes would not be flying over the Channel that night due to fog.

The officers were told they would be “effectively blind” – and should not allow themselves “to be drawn into relaxing and expecting a normal migrant crossing night”. The message warned: “This has the potential to be very dangerous.”

‘Their boat – there’s nothing left’

According to Mohamed Omar, the sea was calm when he and the other passengers departed the French beach around 9pm UK time. Giving his evidence to the Cranston Inquiry from Paris – he still cannot travel to the UK – a ship approached them around an hour into their voyage:

They came up to us to see what we were doing, and shone a light on us. I remember seeing a French flag on the boat. It was a big boat and I am certain it was the French coastguard. I had heard from people I met in the camp in Dunkirk that this happened sometimes, and that the French boat would follow until you reached English waters.

In fact, Mohamed Omar said, the French ship left the travellers again after about an hour. Shortly after this, the problems began.

Travis Van Isacker, CC BY-NC-SA

Around 1am, seawater began entering the dinghy. By now, it was in the vicinity of the Sandettie lightvessel, around 20 miles north-east of Dover. At first, passengers managed to bail out the 13°C water – but soon the flooding became uncontrollable. The dinghy’s inflatable tube began losing pressure, and a couple of the Kurdish men used air pumps to try to keep it inflated. Others tried to prevent panic spreading among the passengers.

Many onboard began to make frantic calls for rescue. What were reported to be leaked transcripts of some of these calls were published by French newspaper Le Monde a year after the sinking. They showed the first distress call from the dinghy was received by the French coastguard at 12.48am. Speaking in English, the caller said there were 33 people on board a “broken” boat.

According to Le Monde, three minutes later, another call was transferred to the French maritime rescue coordination centre at Cap Gris-Nez by an emergency operator who reported: “Apparently their boat – there’s nothing left.” Following procedure, the French coastguard officer asked the caller to send a GPS position by WhatsApp so she could “send a rescue boat as soon as possible”. At 1.05am UK time, the GPS position arrived.

Rather than send a French boat, Le Monde reported that the officer phoned her counterparts in Dover to warn them a dinghy 0.6 nautical miles from the border line would soon be crossing into UK waters. On the other end of the line was the trainee officer, who was handling routine calls that night despite officially only being an observer.

After the call finished, according to Downs’s evidence to the inquiry, the trainee mistakenly told him the dinghy was thought to be “in good condition” – information he recorded in the log for Incident Charlie. This miscommunication may have affected the urgency of the UK’s SAR response, preventing HM Coastguard and Border Force from appreciating the severe distress the “broken” dinghy was in.

Just before 1am, the French coastguard had sent its migrant tracker spreadsheet, containing information on all small boat crossings that night, to HM Coastguard for the first time. It showed four migrant dinghies at sea – which Gris-Nez had been aware of “for many hours”, according to Gibson.

The issue of the French coastguard appearing to withhold information about active small boat crossings had been raised by HM Coastguard’s clandestine operations liaison officer during a July 2021 review. And earlier that very evening, Gibson told one of his colleagues:

Sometimes they just seem to keep it quiet. Like we’ll not get anything – then we’ll get a tracker at three in the morning with 15 incidents, and they go: ‘Mostly these are in your search-and-rescue region.’ Wonderful.

At 1.20am, Downs phoned Border Force Maritime Command in Portsmouth to request a Border Force vessel search for the dinghy Charlie. He provided the GPS position received from his French counterpart and the number of people onboard – but also the incorrect information that “they think it’s in good condition”.

Ten minutes later, the Valiant, Border Force’s 42-metre patrol ship stationed at Dover, was tasked to proceed towards the Sandettie lightvessel. At the same time, the first direct call to the Dover rescue coordination centre came in from Charlie. The distressed caller said they were “in the water” and that “everything [was] finished”.

Around 15 minutes later, at 1.48am, Gibson took a call from 16-year-old Mubin Rizghar Hussein, who spoke good English. Despite the noise and commotion, he managed to provide Gibson with a WhatsApp number – in order to share their GPS position. The transcript of this call records voices shouting in the background: “It’s finished. Finished. Brother, it’s finished.”

A ‘grave and imminent threat to life’

Gibson told the inquiry that after his call with Rizghar Hussein, he had a “gut feeling that this doesn’t feel quite as usual”. By “usual” he meant what was, according to maritime operations officer Downs, a commonly held belief at the Dover coastguard station that with “nine out of ten”“ callers from small boats: “It would generally be overstated that the boat … was sinking, people were drowning … Whatever was going on would be overstated.”

Acting on his gut feeling, at 2.27am Gibson took the unprecedented decision to broadcast a Mayday Relay – denoting a “grave and imminent threat to life”. By maritime law, this alert required other vessels to offer their assistance.

Gibson told the inquiry he did this to get the French warship Flamant to respond. He could see on his radar screen that Flamant was closest to Charlie’s position and was the best vessel to rescue the people if the dinghy really was sinking.

Why the Flamant did not respond is at the centre of an ongoing criminal investigation in France into two of the warship’s officers and five coastguards from Gris-Nez, for “non-assistance of persons in distress”. This investigation’s strict confidentiality obligation means the inquiry was unable to access any information from the French side about their operations that night.

At 2.01 and again at 2.14am, HM Coastguard had received new GPS positions via WhatsApp showing the dinghy to be more than a mile inside UK waters.

Valiant, having been tasked at 1.30am, only exited the port of Dover at 2.22am and would need at least another hour to reach the Sandettie. Despite this, no other vessel was sent to join the search. At 3.11am, when asked during a call by Border Force Maritime Command whether Charlie was “still a Mayday situation”, Gibson replied: “Well, they’ve told me it’s full of water.”

With a total of four small boats being shown in the Channel that night by the French tracker spreadsheet, Gibson suggested there could be as many as 110 people on board these dinghies – beyond Valiant’s capacity for taking on survivors. Nevertheless, Border Force and HM Coastguard opted to “wait and see what the numbers are, and whether Valiant can deal with that … We don’t want to call any other assets out just yet.”

In a call with Christopher Trubshaw, captain of the Coastguard rescue helicopter stationed at Lydd on the Kent coast, aviation tactical commander Dominic Golden explained that Border Force was “not prepared to bring in their crews who are pretty knackered” unless “we can convince them there are people in real danger”. He then asked Trubshaw to search the Channel for the small boats shown in the French tracker, as the surveillance aeroplanes had been unable to take off.

In her closing submission to the inquiry, Sonali Naik, a legal representative of the survivors and bereaved families, highlighted Golden’s “dismissive attitude” towards Charlie’s distress when he gave Trubshaw the reason for the request, which included the following:

As usual, the catalogue of phone calls is beginning to trickle in … You know, the classic ‘I am lost, I am sinking, my mother’s wheelchair is falling over the side’ etc. ‘Sharks with lasers surrounding boat’ and ‘we are all dying’ type of thing.

Nevertheless, Golden asked the helicopter crew to pack a liferaft. “I can’t imagine we’re going to need it but … potentially you get to play with one of your new toys.”

While Golden described his words as “unwise” or “flippant”, Naik said they were “more than that” – suggesting they revealed rescuers’ general perceptions of the occupants of small boats and the widely held scepticism towards their distress calls.

‘We are dying. Where is the boat?’

With the water inside rising fast and their dinghy collapsing, Charlie’s increasingly desperate passengers kept trying to get rescuers to appreciate how dire their situation was.

At 2.31am in the Dover rescue coordination centre, Gibson received a second call from Mubin Rizghar Hussein, who pleaded: “We are dying, where is the boat?”

Gibson replied: “The boat is on its way but it has to get …” only to be interrupted by Rizghar Hussein saying: “We all die. We all die.”

“I get that,” Gibson told the terrified teenager, “but unfortunately, you’re going to be patient and all stay together, because I can’t make the boat come any quicker.” He ended the call saying:

You need to stop making calls because every time you make a call, we think there’s another boat out there – and we don’t want to accidentally go chasing for another boat when it’s actually your boat we’re looking for.

Gibson broke down briefly when recounting this second call during his evidence to the inquiry, explaining:

If you don’t understand what’s fully going on and you’re getting ‘we’re all going to die’, it’s quite a distressing situation to find yourself in, sitting at the end of a phone – effectively helpless. You know where they are, you want to get a boat to them, and you can’t.

Call records also show that coastguards on both sides of the Channel passed responsibility for rescuing the sinking dinghy off to one another. According to Le Monde, during one call a passenger told the French coastguard officer he was “in the water” – to which she replied: “Yes, but you are in English waters.”

The transcript of the last call before Charlie capsized, made at 3.12am, reveals that Downs asked “where are you?” 17 times – despite the caller being unable to answer anything beyond “English waters”. The maritime operations officer finished by instructing the caller to hang up and dial 999: “If it won’t connect on 999, then you’re probably still in French waters.”

In her closing submission, Naik pointed to “discriminatory stereotypes and attitudes towards migrants on small boats which fatally affected the SAR response” for Charlie – as rescuers, in her words, “jumped to premature conclusions”. According to survivor Mohamed Omar:

Because we have been seen as refugees … that’s the reason why I believe the rescue, they did not come at all. We feel like we were … treated like animals.

Fatal assumptions

At 3.27am, Border Force’s ship Valiant arrived at Charlie’s last recorded GPS position (from 2.14am) – but found nothing. Its master, Kevin Toy, decided to head north-easterly towards the Sandettie lightvessel, the way the tide was flowing.

En route, Valiant spotted two other dinghies in the darkness using its night vision – one still making its way towards the English coast, the other stopped in the water. The stationary dinghy was in greater danger from the Channel’s shipping traffic, so Valiant went to it and began rescuing those onboard – radioing back that it had “engaged unlit migrant crafts stopped in the water” with approximately 40 people onboard.

In the Dover rescue coordination centre, Gibson assumed this dinghy could be Charlie and gave Mubin Rizghar Hussein’s name and telephone number so Valiant’s crew could verify whether he was on board. At 4.16am, Gibson himself tried calling the WhatsApp number that Rizghar Hussein had shared, but the call failed.

At 4.20am, Valiant completed its first rescue of the morning. Two more followed after the Coastguard helicopter spotted two other dinghies in the Sandettie area – but nobody in the water. A near-capacity Valiant then returned to Dover just after 8am with 98 survivors on board.

None of the three rescued dinghies matched the description of Charlie. All were in good condition, differently coloured, and with disparate numbers of people onboard – yet the misplaced assumption Charlie had been rescued persisted amid the night’s murky information environment. Gibson stated that, while he had soon received additional information matching Valiant’s first rescue to a different dinghy, he was still “fairly certain Charlie had been picked up”.

“Once Valiant had picked up these [three] boats,” he explained, “we no longer received calls from Charlie, and a call to a known phone number on Charlie failed.” As a result, neither Valiant nor the Coastguard helicopter were sent back out to continue searching for the stricken dinghy.

In fact, Gibson’s call to Rizghar Hussein’s WhatsApp number did not fail because Charlie’s passengers had been rescued – nor because they had thrown their phones into the sea when Border Force arrived. Rather, it was because the dinghy had capsized and everyone had fallen into the Channel’s freezing waters.

‘No one came to our rescue’

In harrowing evidence to the inquiry, Mohamed Omar explained how, as one side of the dinghy deflated, the passengers – “hysterical and crying” – panicked and moved to the opposite side. This shift in weight caused the dinghy to capsize:

The screaming when the boat tipped and people fell in the water was deafening. I have never heard anything as desperate as this. I was not thinking about whether we were going to be rescued any more; it was all about how to stay alive.

As the passengers were thrown into the water, the dinghy flipped on top of them. Mohamed Omar described having to swim out from underneath to catch a breath: “It was dark and I could not really see. It was extremely cold and the sea was rough.”

As he surfaced, he saw Halima Mohammed Shikh, a mother of three also from Somalia and travelling alone, struggling as she couldn’t swim. She screamed his name for help, and he tried to get her back to what was left of the dinghy – but couldn’t. “I think she was one of the first people to drown,” he told the inquiry.

Others managed to cling to the broken inflatable, hoping rescue was on its way – but “no one came to our rescue”. Pushed and pulled by the waves, some lost their grip and drifted away before dawn. Mohamed Omar recalled:

All night, I was holding on to what remained of the boat. In the morning, I could hear the people were screaming and everything. It’s something I cannot forget in my mind.

By the time the sun finally rose at 7.26am, he estimated that no more than 15 people were left clinging to the broken dinghy – adrift on the tide in a busy shipping lane:

I do not recall speaking with anyone in the water. Those who were alive were half-dead. There was nothing we could do any more. I could see bodies floating all around us in the water. I presume most people were either already dead or were unconscious.

Shortly afterwards, Mohamed Omar said he let go of the dinghy and began to swim, thinking to himself: “I am going to die [but] I don’t want to die here. At least if I die whilst swimming, I won’t feel it.”

He swam towards a boat he could see in the distance and, as he got closer, began to wave his life jacket for attention. A French woman, out fishing with her family, saw him and jumped in the water to save him.

As he finished telling his story, Mohamed Omar told the inquiry: “I’m a voice for those people who passed away.”

Bodies are found

Around 1pm on the afternoon of November 24, 12 hours after the first distress calls from Charlie, a French commercial fishing vessel began finding bodies in the sea nine miles north-west of Calais. But as the news came in, no one at HM Coastguard or Border Force appears to have made the connection with Incident Charlie.

Days later, when the accounts of Mohamed Omar’s fellow survivor, Mohammed Shekha Ahmad from Iraqi Kurdistan, and a relative of two of the deceased emerged, the Home Office refuted their claims that the dinghy had sunk in UK waters as “completely untrue”.

However, five days after the disaster, Gibson contacted the small boats tactical commander to share his concerns that the reported deaths could be from Charlie. He had read a news article in which “the survivor states a male called Mubin called the emergency services, which could possibly be the ‘Moomin’ [sic] I spoke to”.

On December 1, clandestine Channel threat commander O’Mahoney responded to a question from the UK’s Joint Committee on Human Rights, as to whether the migrants whose bodies had been found in French waters had made distress calls to the UK authorities. O’Mahoney told the committee:

We are looking into that. To manage your expectation, though, it may never be possible to say with absolute accuracy whether that boat was in UK waters [and] I cannot tell you with any certainty that the people on that particular boat called the UK authorities.

Thanks largely to their grieving families tireless pursuit of the truth, however, it is now possible to say definitively that Charlie had been in UK waters – and that a number of its passengers spoke to HM Coastguard officers.

It was only after these families raised concerns that the disaster had involved the UK authorities that the Department for Transport commissioned a safety investigation into the incident in January 2022. A lawyer for the bereaved families suggested to me that without the threat of legal action, the Department for Transport “would likely not have done anything” – despite this being Britain’s worst maritime disaster for decades. Meanwhile, according to inquiry evidence, the Home Office is understood not to have conducted an internal review or investigation into its role in the disaster.

After a frustrating two years of waiting for the survivors and bereaved families, the Marine Accidents Investigations Branch published its report – which both confirmed most of their accounts and substantiated their criticisms of the SAR response.

Soon afterwards, the Cranston Inquiry was announced. Despite no bodies having been recovered in UK waters, it has been run almost like an inquest. In his final report – to be published by the end of 2025 – Sir Ross Cranston has promised to “consider what lessons can be learned and, if appropriate, make recommendations to reduce the risk of a similar event occurring”.

A ‘crucial and unique opportunity’

HM Coastguard and Border Force officers have repeatedly told the inquiry how the UK’s approach to small boat search-and-rescue has changed since the November 2021 disaster. More officers have been hired, Border Force has contracted additional boats to conduct rescues, information sharing has improved, and cooperation with French colleagues is better. Today, there are significantly more rescue ships on both sides of the Channel which can intervene faster when dinghies come to be in distress, and have undoubtedly saved many lives.

There has also been massive investment in drones, aeroplanes and powerful shore-based cameras to reduce the risk that HM Coastguard loses “maritime domain awareness” again if some of its surveillance aircraft are unable to fly. New technology automatically translates coastguard officers’ messages into different languages and extracts live GPS locations and images from travellers’ mobile devices.

Such investments make it unlikely that another dinghy could be lost in the middle of the Channel after its passengers call for help, in the way Charlie so catastrophically was.

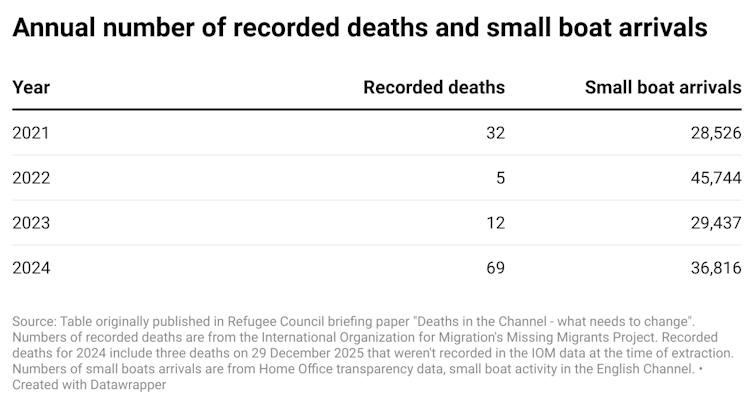

Data from the Refugee Council’s Deaths in the Channel: What Needs to Change.

Nevertheless, people continue dying while attempting to cross the Channel – with 2024 having been by far the deadliest year yet. At least 69 people lost their lives, according to the Refugee Council. So far in 2025, 24 people are documented as dead or missing at the UK-France border by Calais Migrant Solidarity, amid a record number of attempted crossings for the first half of the year.

These people are not dying in “mass casualty incidents” such as Charlie, which attract headlines, but instead one or two at a time as “increasingly overcrowded dinghies” break apart, and people fall into the sea or are crushed inside them.

Some migrants’ rights NGOs have suggested the UK’s “stop the boats” policies, and European efforts to disrupt the supply chain of dinghies and other equipment used in crossings, has driven such deadly overcrowding.

And with the French government having promised to change its rules of engagement to intercept dinghies once at sea, amid reports of French police wading into the surf to slash dinghies with knives, the NGOs fear Channel migrants are facing ever greater dangers.

But it is also unlikely that the circumstances surrounding more recent deaths in the Channel will ever be investigated as thoroughly as Incident Charlie, if at all. Lawyers for the bereaved families have therefore been keen to highlight the Cranston Inquiry’s “crucial and unique opportunity” not only to look back and offer answers about one of Britain’s worst maritime disasters in recent decades – but to look forwards and “prevent the further loss of life at sea”.

The survivors, families and migrants’ rights organisations who contributed their evidence thus hope the inquiry’s recommendations go beyond purely operational and administrative improvements to search-and-rescue, to address the fundamental role that UK, France and European border policies play in why more people are dying in the Channel, despite the improvements to search-and-rescue strategies and resources.

Above all, they ask why only some people are able to travel to the UK in comfort and safety while others must make the journey in precarious, overcrowded inflatable dinghies – and thus entrust their lives to the search-and-rescue services whose success can never be guaranteed. As Halima Mohammed Shikh’s cousin, Ali Areef, told the inquiry:

It makes me feel sick to think about crossing the Channel in a ferry where others including a member of my family lost their lives because there was no other way to cross. I will never take a ferry across the Channel again.

For you: more from our Insights series:

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

![]()

Travis Van Isacker gratefully acknowledges the support of the Economic and Social Research Council

(UK) (Grant Ref: ES/W002639/1).

– ref. What caused Britain’s deadliest ‘small boat’ disaster, and how can another be avoided? – https://theconversation.com/what-caused-britains-deadliest-small-boat-disaster-and-how-can-another-be-avoided-260830