Source: The Conversation – USA (2) – By Sky Hooler, Ph.D. Student in Environmental Science, University at Albany, State University of New York

Lush forests and crisp mountain air have drawn people to New York’s Adirondack Mountains for centuries. In the late 1800s, these forests were a haven for tuberculosis patients seeking the cool, fresh air. Today, the region is still a sanctuary where families vacation and hikers roam pristine trails.

However, hidden health dangers have been accumulating in these mountains since industrialization began.

Tiny metal particulates released into the air from factories, power plants and vehicles across the Midwest and Canada can travel thousands of miles on the wind and fall with rain. Among them are microscopic pollutants such as lead and cadmium, known for their toxic effects on human health and wildlife.

For decades, factories released this pollution without controls. By the 1960s and 1970s, their pollution was causing acid rain that killed trees in forests across the eastern U.S., while airborne metals were accumulating in even the most remote lakes in the Adirondacks.

Detroit Publishing Company photograph collection (Library of Congress)

As paleolimnologists, we study the history of the environment using sediment cores from lake bottoms, where layers of mud, leaves and pollen pile up over time, documenting environmental and chemical changes.

In a recent study, we looked at two big questions: Have lakes in the Northeast U.S. recovered from the era of industrial metal pollution, and did the Clean Air Act, written to help stop the pollution, work?

Digging up time capsules

On multiple summer trips between 2021 and 2024, we hiked into the Adirondacks’ backcountry with 60-pound inflatable boats, a GPS and piles of long, heavy metal tubes in tow.

We focused on four ponds – Rat, Challis, Black and Little Hope. In each, we dropped cylindrical tubes that plunge into the darkness of the lake bottom. The tubes suction up the mud in a way that preserves the accumulated layers like a history book.

Back in the lab, we sliced these cores millimeter by millimeter, extracting metals such as lead, zinc and arsenic to analyze the concentrations over time.

The changes in the levels of metals we found in different layers of the cores paint a dramatic picture of the pristine nature of these lakes before European settlers arrived in the area, and what happened as factories began going up across the country.

A century plagued by contamination

Starting in the early 1900s, coal burning in power plants and factories, smelting and the growing use of leaded gasoline began releasing pollutants that blew into the region. We found that manganese, arsenic, iron, zinc, lead, cadmium, nickel, chromium, copper and cobalt began to appear in greater concentrations in the lakes and rose rapidly.

At the same time, acid rain, formed from sulfur and nitrogen oxides from coal and gasoline, acted like chemical shovels, freeing more metals naturally held in the bedrock and forest soils.

Will & Deni McIntyre/Corbis Documentary via Getty Images

The result was a cascade of metal pollution that washed down the slopes with the rain, winding through creeks and seeping into lakes.

All of this is captured in the lake sediment cores.

As extensive logging and massive fires stripped away vegetation and topsoil, the exposed landscapes created express lanes for metals to wash downhill. When acidification met these disturbed lands, the result was extraordinary: Metal levels didn’t just increase, they skyrocketed. In some cases, we found that lead levels in the sediment reached 328 parts per million, 109 times higher than natural preindustrial levels. That lead would have first been in the air, where people were exposed, and then in the wildlife and fish that people consume.

These particles are so small that they can enter a person’s lungs and bloodstream, infiltrate food webs and accumulate in ecosystems.

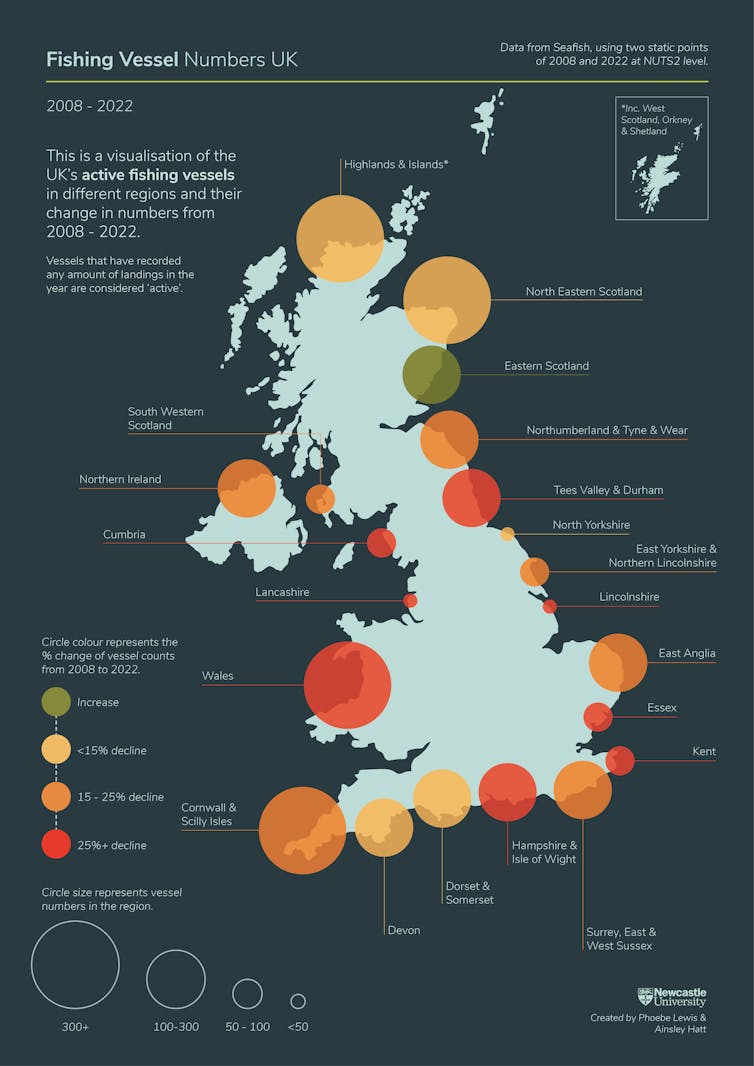

Sky Hooler

Then, suddenly, the increase stopped.

A public outcry over acid rain, which was stripping needles from trees and poisoning fish, led to major environmental legislation, including the initiation of the Clean Air Act in 1963. The law and subsequent amendments in the following decades began reducing sulfur dioxide emissions and other toxic pollutants. To comply, industries installed scrubbers to remove pollutants at the smokestack rather than releasing them into the air. Catalytic converters reduced vehicle exhaust, and lead was removed from gasoline.

The air grew cleaner, the rain became less acidic, and our sediment cores show that the lakes began to heal through natural biogeochemical processes, although slowly.

Patrick Dodson

By 1996, atmospheric lead levels measured at Whiteface Mountain in the Adirondacks had declined by 90%. National levels were down 94%. But in the lakes, lead had decreased only by about half.

Only in the past five years, since about 2020, have we seen metal concentrations within the lakes fall to less than 10% of their levels at the height of pollution in the region.

Our study is the first documented case of a full recovery in Northeast U.S. lakes that reflects the recovery seen in the atmosphere.

It’s a powerful success story and proof that environmental policy works.

Looking forward

But the Adirondacks aren’t entirely in the clear. Legacy pollution lingers in the soils, ready to be remobilized by future disturbances from land development or logging. And there are new concerns. We are now tracking the rise of microplastics and the growing pressures of climate change on lake ecosystems.

Recovery is not a finish line; it’s an ongoing process. The Clean Air Act and water monitoring are still important for keeping the region’s air and water clean.

Though our findings come from just a few lakes, the implications extend across the entire Northeast U.S. Many studies from past decades documented declining metal deposition in lakes, and research has confirmed continued reductions in metal pollutants in both soils and rivers.

In the layers of lake mud, we see not only a record of damage but also a testament to nature’s resilience, a reminder that with good legislation and timely intervention, recovery is possible.

![]()

Sky Hooler received funding from National Science Foundation with

the Geological Society of America Graduate Student Geoscience

Research Grant #1949901, 2021.

Aubrey Hillman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Industrial pollution once ravaged the Adirondacks − decades of history captured in lake mud track their slow recovery – https://theconversation.com/industrial-pollution-once-ravaged-the-adirondacks-decades-of-history-captured-in-lake-mud-track-their-slow-recovery-260182