Source: The Conversation – UK – By Kevin Olsen, UKSA Mars Science Fellow, Department of Physics, University of Oxford

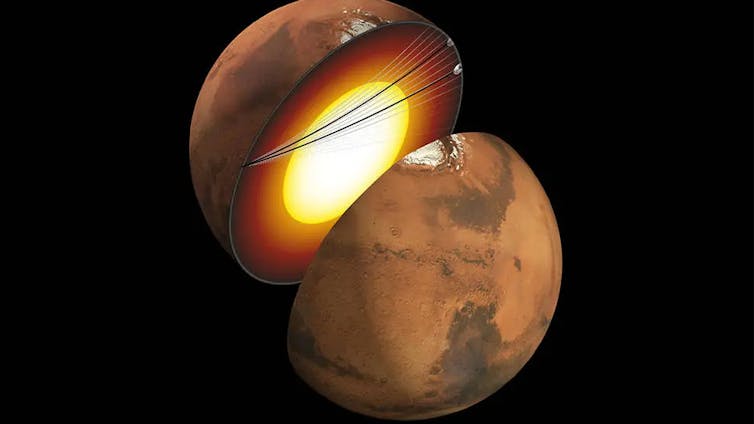

Scientists have discovered that Mars has an interior structure similar to Earth’s. Results from Nasa’s Insight mission suggest that the red planet has a solid inner core surrounded by a liquid outer core, potentially resolving a longstanding mystery.

The findings, which are published in Nature, have important implications for our understanding of how Mars evolved. Billions of years ago, the planet may have had a thicker atmosphere that allowed liquid water to flow on the surface.

This thicker atmosphere may have been kept in place by a protective magnetic field, like the one Earth has. However, Mars lacks such a field today. Scientists have wondered whether the loss of this magnetic field led to the red planet losing its atmosphere to space over time and becoming the cold, dry desert it is today.

A key property of the Earth is that its core has a solid centre and liquid outer core. Convection within the liquid layer creates a dynamo, producing the magnetic field. The field deflects charged particles ejected by the Sun, preventing them from stripping the Earth’s atmosphere away over time and leading to the habitable conditions we know and enjoy.

From residual magnetisation in the crust, we think that Mars did once have a magnetic field, possibly from a core structure similar to that of Earth. However, scientists think that the core must have cooled and stopped moving at some point in its history.

On the surface of Mars there is a tremendous amount of evidence that liquid water once flowed, suggesting more hospitable conditions in the past. The evidence comes in many forms, including dry lake beds with minerals that formed under water, or the dramatic valley networks carved by rivers and streams. However, the Martian atmosphere is thin today and the necessary amount of water is nowhere to be found.

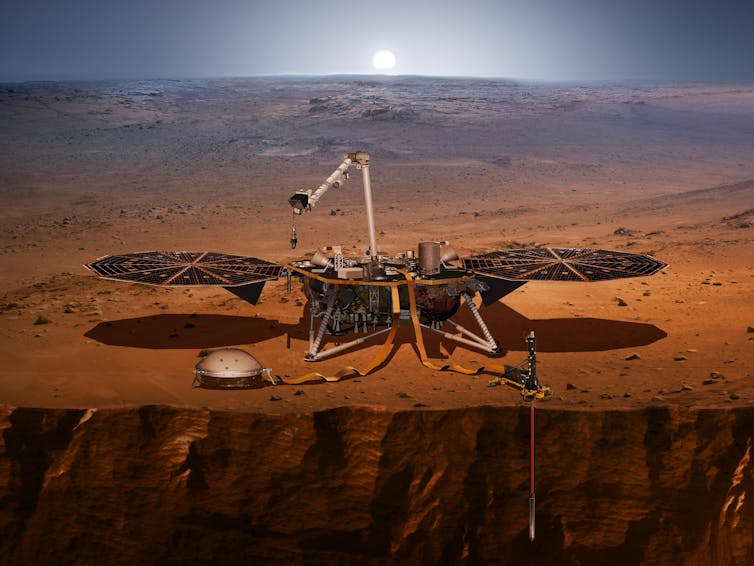

Teams working with the seismometers on Nasa’s InSight Mars lander first identified the Martian core and determined that it was actually still liquid. Now, the new results from Huixing Bi, at the University of Science and Technology of China in Hefei and colleagues, show that there may also be a solid layer inside the liquid core.

The nature of the interior structure of Mars has been an intriguing mystery. Was it ever like Earth’s, with a dynamic liquid layer around a solid centre? Or did Mars’ smaller size prevent such a formation? How big must a planet be to gain the protection of a magnetic field, like Earth’s, and support a habitable climate?

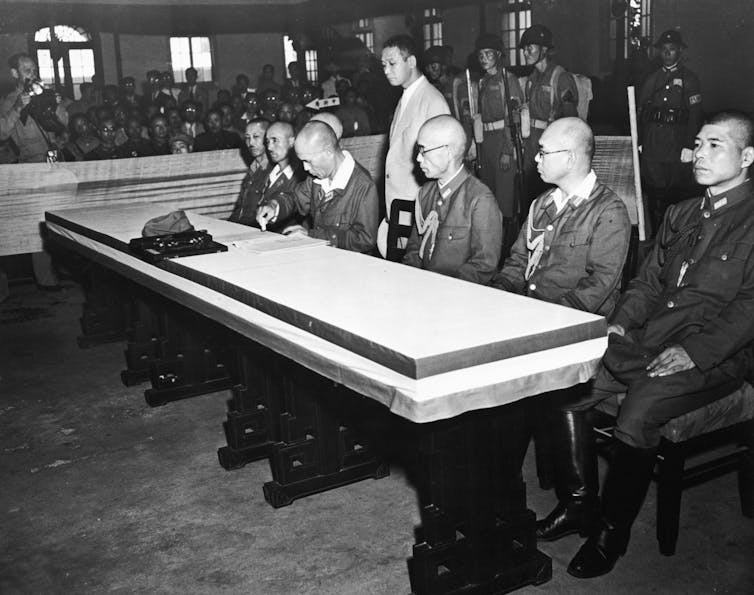

To understand what happened, how Mars evolved, we need to understand Mars today. These questions about Mars’ atmosphere, water, and core have motivated several high profile Mars missions. While the Nasa Mars rovers, Spirit, Opportunity, Curiosity, and Perseverance have studied the surface mineralogy, the European Space Agency’s ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter is studying the water cycle, Nasa’s Maven spacecraft is studying atmospheric loss to space, and Nasa’s InSight lander was sent to study seismic activity.

JPL-Caltech

In 2021, Simon Stähler, from ETH Zurich in Switzerland, and colleagues, published a seminal paper from the InSight mission. In it, they presented an analysis of the way that seismic waves pass through Mars from Mars quakes in the vicinity of InSight, through the mantle, through the core, and then reflecting off the other side of the planet and reaching InSight.

They detected evidence of the core for the first time and were able to constrain its size and density. They modelled a core with a single liquid layer that was both larger and less dense than expected and without a solid inner core. The size was huge, about half of Mars’ radius of 1,800 km, and the low density implied that it was full of lighter elements. The light elements, such as carbon, sulphur, and hydrogen, change the core’s melt temperature and affect how it could crystallise over time, making it more likely to remain liquid.

The solid inner core (610 km radius) found by Huxing Bi and colleagues is hugely significant. The very presence of a solid inner core shows that crystallisation and solidification is taking place as the planet cools over time.

The core structure is more like Earth’s and therefore more likely to have produced a dynamo at some point. On Earth, it is the thermal (heat) changes between the solid inner core, the liquid layer, and the mantle that drive convection in the liquid layer and create the dynamo that leads to a magnetic field. This result makes it more likely that a dynamo on Mars was possible in the past.

With Simon Stähler and co-authors reporting a fully liquid core and Huxing Bi and colleagues reporting a solid inner core, it might seem as if there will be some controversy. But that is not the case. This is an excellent example of progress in scientific data collection and analysis.

JPL-Caltech

Competing models of Mars

InSight landed in November 2018 and its last contact with Earth occurred in December 2022. With Stähler publishing in 2021, there is some new data from InSight to look at. Stähler’s model was revised in 2023 by Henri Samuel, from the Université Paris Cité, and colleagues. A revised core size and density helped reconcile the InSight results with some other pieces of evidence.

In Stähler’s paper, a solid inner core is specifically not ruled out. The authors state that the signal strength of the analysed data was not strong enough to be used to identify seismic waves crossing an inner core boundary. This was an excellent first measurement of the core of Mars, but it left the question of additional layers and structure open.

For the latest study in Nature, the scientists achieved their result through a careful selection of specific seismic event types, at a certain distance from InSight. They also employ some novel data analysis techniques to get a weak signal out of the instrument noise.

This result is sure to have an impact within the community, and it will be very interesting to see whether additional re-analyses of the InSight data support or reject their model. A thorough discussion of the broader geological context and whether the model fits other available data that constrain the core size and density fit will also follow.

Understanding the interior structure of planets in our Solar System is critical to developing ideas about how they form, grow, and evolve. Prior to InSight, models for Mars that were similar to Earth were investigated, but were certainly not favoured.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Mars has a solid core, resolving a longstanding planetary mystery — new study – https://theconversation.com/mars-has-a-solid-core-resolving-a-longstanding-planetary-mystery-new-study-264325