Source: The Conversation – USA – By Anne Schmitz, Associate Professor of Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Stout

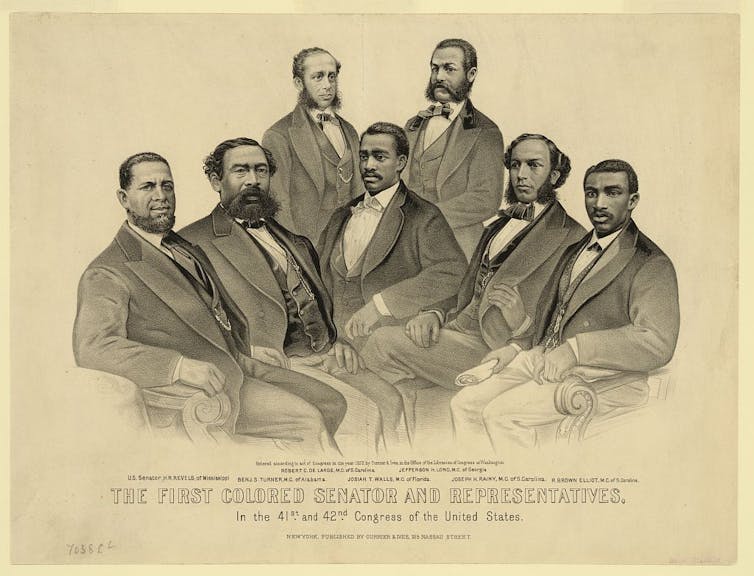

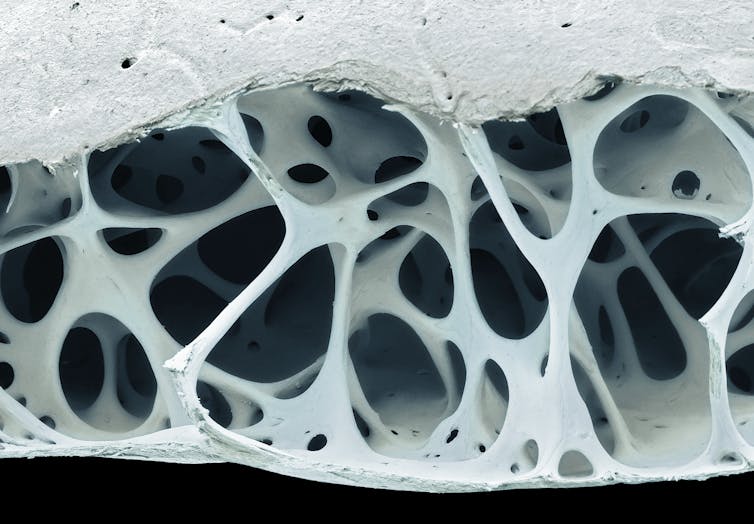

If you break open a chicken bone, you won’t find a solid mass of white material inside. Instead, you will see a complex, spongelike network of tiny struts and pillars, and a lot of empty space.

It looks fragile, yet that internal structure allows a bird’s wing to withstand high winds while remaining light enough for flight. Nature rarely builds with solid blocks. Instead, it builds with clever, porous patterns to maximize strength while minimizing weight.

Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library via Getty Images

Human engineers have always envied this efficiency. You can see it in the hexagonal perfection of a honeycomb, which uses the least amount of wax to store the most honey, and in the internal spiraling architecture of seashells that resist crushing pressures.

For centuries, however, manufacturing limitations meant engineers couldn’t easily copy these natural designs. Traditional manufacturing has usually been subtractive, meaning it starts with a heavy block of metal that is carved down, or formative, which entails pouring liquid plastic into a mold. Neither method can easily create complex, spongelike interiors hidden inside a solid shell.

If engineers wanted to make a part stronger, they generally had to make it thicker and heavier. This approach is often inefficient, wastes material and results in heavier products that require more energy to transport.

I am a mechanical engineer and associate professor at the University of Wisconsin-Stout, where I research the intersection of advanced manufacturing and biology. For several years, my work has focused on using additive manufacturing to create materials that, like a bird’s wing, are both incredibly light and capable of handling intense physical stress. While these “holey” designs have existed in nature for millions of years, it is only recently that 3D printing has made it possible for us to replicate them in the lab.

The invisible architecture

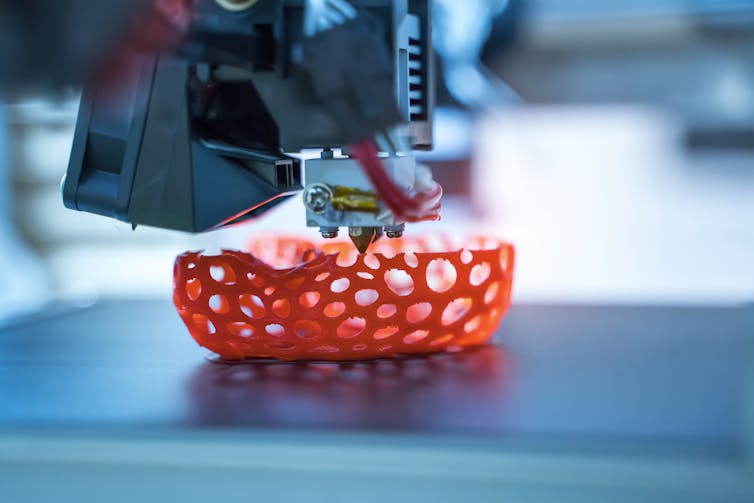

That paradigm changed with the maturation of additive manufacturing, commonly known as 3D printing, when it evolved from a niche prototyping tool into a robust industrial force. While the technology was first patented in the 1980s, it truly took off over the past decade as it became capable of producing end-use parts for high-stakes industries like aerospace and health care.

kynny/iStock via Getty Images

Instead of cutting away material, printers build objects layer by layer, depositing plastic or metal powder only exactly where it’s needed based on a digital file. This technology unlocked a new frontier in materials science focused on mesostructures.

A mesostructure represents the in-between scale. It is not the microscopic atomic makeup of the material, nor is it the macroscopic overall shape of the object, like a whole shoe. It is the internal architecture, including the engineered pattern of air and material hidden inside.

It’s the difference between a solid brick and the intricate iron latticework of the Eiffel Tower. Both are strong, but one uses vastly less material to achieve that strength because of how the empty space is arranged.

From the lab to your closet

While the concept of using additive manufacturing to create parts that take advantage of mesostructures started in research labs around the year 2000, consumers are now seeing these bio-inspired designs in everyday products.

The footwear industry is a prime example. If you look closely at the soles of certain high-end running shoes, you won’t see a solid block of foam. Instead, you will see a complex, weblike lattice structure that looks suspiciously like the inside of a bird bone. This printed design mimics the springiness and weight distribution found in natural porous structures, offering tuned performance that solid foam cannot match.

Engineers use the same principle to improve safety gear. Modern bike helmets and football helmet liners are beginning to replace traditional foam padding with 3D-printed lattices. These tiny, repeating jungle gym structures are designed to crumple and rebound to absorb the energy more efficiently than solid materials, much like how the porous bone inside your own skull protects your brain.

Testing the limits

In my research, I look for the rules nature uses to build strong objects.

For example, seashells are tough because they are built like a brick wall, with hard mineral blocks held together by a thin layer of stretchy glue. This pattern allows the hard bricks to slide past each other instead of snapping when put under pressure. The shell absorbs energy and stops cracks from spreading, which makes the final structure much tougher than a solid piece of the same material.

I use advanced computer models to crush thousands of virtual designs to see exactly when and how they fail. I have even used neural networks, a type of artificial intelligence, to find the best patterns for absorbing energy.

My studies have shown that a wavy design can be very effective, especially when we fine-tune the thickness of the lines and the number of turns in the pattern. By finding these perfect combinations, we can design products that fail gradually and safely – much like the crumple zone on the front of a car.

By understanding the mechanics of these structures, engineers can tailor them for specific jobs, making one area of a product stiff and another area flexible within a single continuous printed part.

The sustainable future

Beyond performance, mimicking nature’s less-is-more approach is a significant win for sustainability. By “printing air” into the internal structure of a product, manufacturers can use significantly less raw material while maintaining the necessary strength.

As industrial 3D printing becomes faster and cheaper, manufacturing will move further away from the solid-block era and closer to the elegant efficiency of the biological world. Nature has spent millions of years perfecting these blueprints through evolution – and engineers are finally learning how to read them.

![]()

Anne Schmitz does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. Building with air – how nature’s hole-filled blueprints shape manufacturing – https://theconversation.com/building-with-air-how-natures-hole-filled-blueprints-shape-manufacturing-270640