Source: The Conversation – UK – By Tom Birkett, Professor of Old English and Old Norse, University College Cork

At a press conference announcing that the suspect in the shooting of Charlie Kirk had been detained, FBI director Kash Patel ended his speech with a personal message to his “brother”, saying: “We have the watch, and I’ll see you in Valhalla.”

Many people commenting on the press conference reacted to this confusing reference to Valhalla with a mixture of amusement and disdain, with some pointing out the contradiction of eulogising a Christian nationalist with reference to the pagan afterlife.

For scholars of the Vikings, Patel’s reference to Valhalla looked like something far more sinister. To understand why, we need to know both what Valhalla meant to the Vikings, and what it means in political discourse today.

Read more:

US Capitol riot: the myths behind the tattoos worn by ‘QAnon shaman’ Jake Angeli

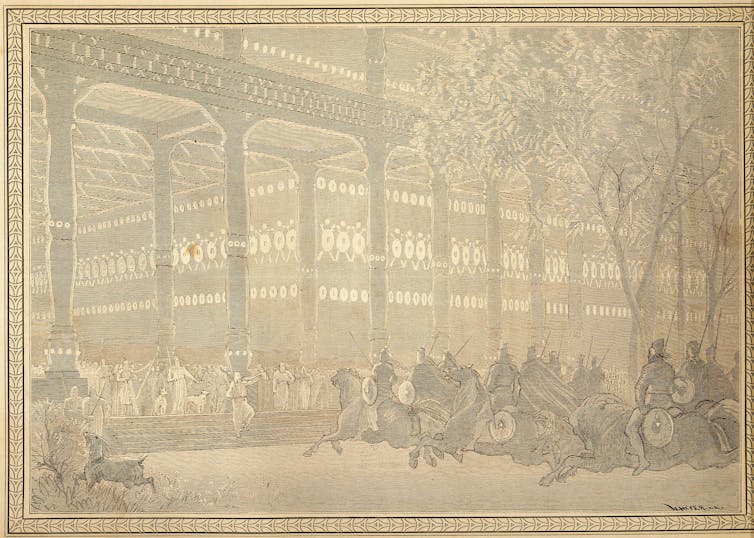

The Norse peoples had a developed concept of the afterlife. The desirable destination for Norse warriors was Valhalla, the hall of the slain, where Odin watched over his band of chosen warriors as they prepared for Ragnarök, the world-destroying battle against the giants. Only those who died a heroic death in combat were brought to Valhalla by the Valkyries.

Those who died by sickness, old age or accident – or who had committed murder and other dishonourable crimes – seem to have been excluded from this martial afterlife. Some believed that you could cheat the Norse gods by arranging to be buried with deliberately worn and damaged weapons as if you had seen heavy combat. There’s a lot we don’t know.

from Wikimedia Commons

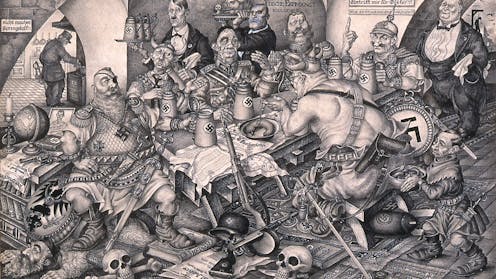

What we do know is that in the 1930s the concept of Valhalla, along with the image of the heroic Viking and many of the symbols of Norse mythology, had a profound appeal to Nazi thought leaders. They looked to Norse mythology as a survival of a wider “Germanic” culture that had been erased by Judeo-Christian dominance.

The Nordic “race” was held up as the Aryan ideal. Norse cultural remnants were used to add legitimacy to the idea of a glorious German past. Heinrich Himmler in particular repurposed Norse symbols for use by the SS.

Today, many white supremacist and neo-Nazi groups continue to brand themselves using a widening range of symbols taken from Norse mythology. One aspect of Norse culture that has gained increasing prominence in the past few decades is the specific co-opting of Valhalla by those who are prepared to kill, and die, in the cause of “protecting” an endangered white supremacy.

Valhalla in terrorist manifestos

The most chilling example of the co-option of the phrase “see you in Valhalla” is found in the manifestos published by far-right terrorists in the wake of their atrocities.

In 2019, Brenton Tarrant carried out mass shootings at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, in which 51 people were killed. He published a rambling manifesto in which he attempted to justify his actions, and touted the “great replacement” conspiracy theory which holds that Jewish elites are deliberately engineering the replacement of white populations through immigration.

This has since become a far-right talking point and was pushed by Charlie Kirk on his show. Tarrant signed off his diatribe against multiculturalism and “white genocide” by saying “Goodbye, god bless you all and I will see you in Valhalla.”

Tarrant in turn influenced other far-right terrorists. One such terrorist, Peyton Gendron, was convicted of the Buffalo mass shooting in 2022 in which ten black Americans were murdered. Gendron plagiarised much of his 180-page manifesto, and similarly ends his screed with the statement: “I hope to see you in Valhalla.”

By invoking Valhalla, these terrorists are attempting to cast themselves as warriors in the Viking tradition. There is, of course, nothing remotely heroic about gunning down unarmed civilians.

But the point is that this reference doesn’t require any understanding of the Norse tradition. In this context it comes directly from the Nazi’s fetishisation of violent death to secure the racial purity of Germany.

From terrorists to the FBI

Rather than borrowing from extremist discourse, Patel may have been influenced by the use of “til Valhalla” by the US marines to honour fallen comrades – including those who died by suicide. This is a use which has been traced back to the influence of Norwegian Nato forces in Afghanistan, who may have used “til Valhalla” as a kind of battle cry. Of course, the optics of using a military honorific to commemorate the assassination of a civilian is problematic in itself.

Patel’s “see you in Valhalla” was much closer in its wording to the sign off used by far-right terrorists – but even this phrasing was unlikely to have been lifted directly from extremists. It is more likely an example of a phenomenon often observed in the study of the far-right online ecosystem, which is the seepage of extreme right discourse into more mainstream spaces.

Neo-Nazi groups use memes, shitposting and humour as a deliberate strategy to seed increasingly extreme ideas into groups amenable to their message.

It isn’t hard to find references to Valhalla commercialised, repackaged as inspirational Viking quotes for Maga consumption, referencing cancel culture, or even using Norse video games as a gateway to white supremacy. In this way, the more mainstream right often ends up sharing and amplifying extremist messaging.

Patel’s reference to Valhalla was at the very least a huge misstep by a government official trying to appeal to the Maga base and elevate Kirk’s tragic killing into a heroic warrior’s death.

While he may not have made his reference to Valhalla in knowledge of its association with far-right terrorism, it nevertheless served as a signal to white supremacists. As reported elsewhere, there was a lot of engagement from the extreme right on social media, but their posts tended to ridicule Patel.

His words prompted memes on social media playing on the apparent absurdity of someone of Patel’s ethnicity cosplaying as a Viking. And among this racially tinged mockery, there was also some revelling in the fact that a stock phrase of violent white supremacy had found its way into the mouth of the director of the FBI.

![]()

Tom Birkett receives funding from the European Union (ERC, NorseMap, Project Number 101169706). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.”

– ref. ‘See you in Valhalla’: how the FBI director waded into the far-right’s obsession with the Vikings – https://theconversation.com/see-you-in-valhalla-how-the-fbi-director-waded-into-the-far-rights-obsession-with-the-vikings-266281