Source: The Conversation – USA (3) – By David Higgins, Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus

More than three-quarters of U.S. counties and jurisdictions are experiencing declines in childhood vaccination rates, a trend that began in 2019, according to a September 2025 NBC News–Stanford University investigation. The report also found a “large swath” of the U.S. no longer has the “basic, ground-level immunity” needed to stop the spread of measles.

Dr. David Higgins, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado CU Anschutz Medical Center and a pediatrician who researches vaccines, discusses the dangers of not vaccinating your children.

The Conversation has collaborated with SciLine to bring you highlights from the discussion, edited for brevity and clarity.

What vaccines are typically required for schoolchildren, and why?

David Higgins: The vaccine requirements for kids to attend school are set by states, not the federal government. Most states require kindergartners get vaccines for pertussis – that’s whooping cough – and tetanus, measles, mumps, rubella and chickenpox.

For older kids, a booster of the tetanus and pertussis vaccine is typically required, as well as a vaccine for meningococcal disease.

Vaccines reduce the risk of outbreaks in places where transmission of these diseases is easy. Not only do vaccinations help keep both students and teachers safe, it also encourages overall higher community coverage for these vaccines.

How do scientists track the safety of vaccines over time?

Higgins: Before vaccines are approved, they undergo rigorous trials. During this process, scientists look at the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, testing it first in small groups to assess safety, then in larger groups to confirm protection and detect uncommon side effects. That process continues after the vaccine is approved. Those systems continually monitor the safety of vaccines, both here in the U.S. as well as around the world.

What are the vaccination coverage trends for kindergartners?

Higgins: What we have seen is a small downward trend since 2019, the year prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. It slipped from 95% of new kindergartners being up to date on many of their routine vaccines to about 92%.

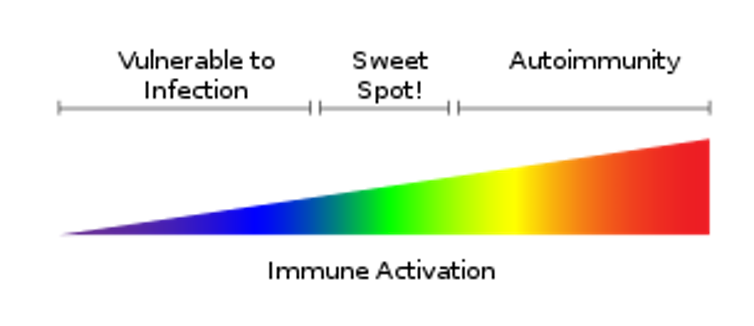

That’s a small percentage decrease, so a great majority of parents are still vaccinating their kids. But at the same time, anything below our target of 95% for diseases like measles becomes a problem, because that’s below the level that’s needed for what we call herd immunity, or community immunity. When that happens, it’s not a matter of if, but when, we see an outbreak of these infectious diseases.

And while nationwide rates are important to look at, outbreaks happen at local community levels. For example, earlier this year, an outbreak of measles in West Texas spread rapidly through communities where vaccination rates had slipped well below the state average.

So, the vaccination rate at your own school or community is much more meaningful than what the national vaccination rate is.

How do non-medical vaccine exemptions work?

Higgins: First, actual medical exemptions are rare, and these occur when the vaccine is unsafe for the child to receive, like when he or she has a known severe allergic reaction to vaccine ingredients.

Non-medical exemptions for vaccines are often for religious, personal or philosophical reasons. They have been increasing for the past several years, rising from the range of 1 to 2% up to 3.6% in the 2024–25 school year. That’s a small increase, but again, it’s still concerning.

{What are some reasons why parents are} Why are some parents vaccine hesitant?

Higgins: There are multiple reasons. These include misinformation which algorithm-driven echo chambers on social media can spread at an alarming rate right now. Also, Americans report less trust in institutions and experts, and studies have found growing partisanship around vaccines.

Additionally, vaccines are victims of their own success. They have worked so well that many diseases like polio aren’t routinely seen anymore. That might lead a parent to think the risk for their child is so low that the vaccine is not necessary. But the fact is, vaccines are simply holding these diseases at bay. And as vaccination rates drop, these diseases will come back and more kids will be at risk.

What advice do you have for parents?

Higgins: The most important thing you can do as a parent is to keep your kids up to date on required vaccines. That includes the annual flu shot. Follow your state’s requirements and current recommendations from trusted sources like the American Academy of Pediatrics and your own personal pediatrician to know which vaccines your child should have.

You also want to reinforce other common sense approaches to keeping your children healthy. Make sure they know how to wash their hands properly and that they stay home when they’re sick. Teach them to sneeze and cough into their elbow instead of into their hands – even though doing so isn’t a perfect solution.

As a pediatrician, I love when my families come and talk to me about their concerns. I help them walk through their worries so they can feel more confident that they’re making a truly informed decision that’s in the best interest of their child’s health.

SciLine is a free service based at the American Association for the Advancement of Science, a nonprofit that helps journalists include scientific evidence and experts in their news stories.

![]()

David Higgins is a member of the American Academy of Pediatrics. He is also on the board of directors (volunteer) for Immunize Colorado.

– ref. Even small drops in vaccination rates for US children can lead to disease outbreaks – https://theconversation.com/even-small-drops-in-vaccination-rates-for-us-children-can-lead-to-disease-outbreaks-265555