Source: The Conversation – UK – By Ayman El Hajjar, Senior Lecturer & Head of the Cyber Security Research Group, University of Westminster

When cybercriminals targeted the UK nursery chain Kido, it represented a disturbing new low for the hackers. They threatened to expose personal data about young children and their families, shocking parents and cybersecurity experts alike.

The Kido hack is far from an isolated incident. Cyberattacks have struck organisations across many sectors in the last year, disrupting businesses from retail to manufacturing.

These recurring attacks highlight an important reality – cybercrime has become a very profitable activity. While the official advice is not to pay hackers, the frequency of these attacks suggests that many companies do. They will want to avoid losing their data or having their business and reputation damaged. But most will never admit to paying up.

Whenever there is money involved, more criminals want to participate – which has led to cybercrime becoming an organised industry. Cybercrime has shifted from individual and uncoordinated group attacks to an established business model that generates revenue and mirrors genuine companies.

This model has its own supply chains, affiliates (for example, criminals who use the malware rather than developing it) and even customer support.

The cybercrime ecosystem has evolved to run using the “as-a-service” model. For legitimate businesses, this is an efficiency model that lets them pay to use something “as a service”, rather than purchasing it. Just as businesses use software or security as a service, criminals have mirrored this model into an similar underground economy of cybercrime.

In this underground market, hackers sell ready-made malware, rent out botnets (networks of infected devices), and run payment platforms. They even go as far as providing customer support and help pages for the criminals they serve.

Their customers may shop for ransomware as a service when looking to extort ransoms from victims. Others, looking to cause disruption rather than financial gain, rent botnets to conduct “denial of service” attacks that flood the victim’s systems with traffic and disables them.

In the cybercrime economy, criminals known as “initial access brokers” act as middlemen. These are skilled cybercriminals who break into systems, providing the initial access and selling it as a package for others to use.

The packages often include stolen data, usernames and passwords, or even direct access to compromised networks. This essentially opens the door for cybercriminals with fewer skills to compromise businesses.

Business is booming

This business model is not only thriving right now – it will also persist. That’s just simple economics – everyone involved in the “business” benefits. This includes the experienced hackers and malware developers who take their cut, the brokers selling bundled services and the service-hosting and payment-platform providers taking their share. It also includes the affiliate criminals carrying out attacks and collecting their profits.

This makes it low-risk and profitable, effectively the definition of a successful business. Societal attitudes towards hackers often glamorise them as genius outsiders, while hacking itself – particularly when large corporations are the target – can mistakenly be seen as a lesser crime.

But the truth is that when the cybercrime business model succeeds, it has a lasting impact on the wider economy. Trust in businesses in the UK and beyond is damaged.

The attacks on UK retailers such as M&S and Co-op were carried out using a cybercrime service called DragonForce. This is available for a fee, reportedly set at 20% of the ransom payment. In the case of M&S and Co-op, it caused major disruption to their operations, and millions of pounds in losses.

Meanwhile, the attack on the Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) caused production at the carmaker to be halted for weeks, resulting in a huge loss.

The JLR attack caused a ripple effect on sales, deliveries, the workforce and smaller businesses in the supply chain. These companies may face bankruptcy if proceeds from the loan underwritten by the government do not reach them all.

To interrupt this recurrence of attacks, it’s vital to break the cybercriminals’ model by addressing the two fundamentals that make it successful.

First, businesses should stop paying the criminals. As long as they pay, criminals will try their luck. But it is reported that nearly 50% of companies do pay up. This is money that will fuel this crime and encourage the hackers.

Second, companies must build better resilience into their infrastructure and operations. While companies’ security has improved greatly, they are still not investing enough in things such as AI to improve their resilience to attack and their ability to keep operating (or at least to minimise disruption).

This was evident in the attacks on UK businesses. It took M&S four months to restore all of its services, while JLR’s production will not be at full capacity for several weeks.

Both Harrods and Co-op maintained operations during their incidents. This minimised interruptions, prevented large data losses and reduced the financial hit to the businesses.

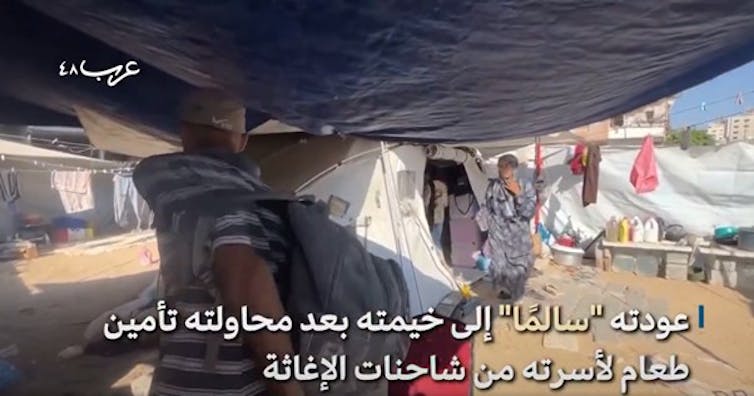

Brian Minkoff/Shutterstock

There are no quick fixes, but there are steps businesses can take to make cybercrime less profitable for criminals and less disruptive for victims. The UK government is heading in the right direction with the Cyber Security and Resilience Bill and its consultations on ransomware payments.

But the real change must come from companies themselves. Without commitment, the strongest policy and legislation will remain words on paper. While prevention remains critical for a company, resilience if the worst happens is what really decides how much damage an attack can cause.

If companies can maintain operations and refuse to pay ransoms, cybercriminals lose their extortion power. And without that power there will be less profit and so less interest. But maybe most importantly, fewer families like those affected by the Kido attack will worry about their children’s data being held hostage.

![]()

Ayman El Hajjar does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

– ref. As long as the cybercriminals’ business model works, companies are vulnerable to attack – https://theconversation.com/as-long-as-the-cybercriminals-business-model-works-companies-are-vulnerable-to-attack-266521