Source: The Conversation – UK – By Neil Ward, Professor of Rural and Regional Development at the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, University of East Anglia

In 2022, six days before Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine and destabilised energy and food supplies, my colleagues and I started building a network of researchers, practitioners and policymakers to identify ways to create a more sustainable future for the UK food system. Three years later and this network has more than 3,000 members.

The UK’s food system is facing mounting pressures from the effects of climate change, increasing geopolitical instability and concerns about its impact on economic productivity and the environment. So how can we strengthen the resilience of our system when the future looks so uncertain?

Sticking with the status quo is not an option. Large-scale change is inevitable over the next two decades, especially as the effects of climate change continue to unfold.

We have developed four plausible scenarios for what the UK food system might look like in a net zero 2050, each with different socio-economic conditions.

What if Trump returned to power or not? What if geopolitics became more, or less, unstable? What would happen if the rule-based system of international trade broke down or was strengthened? We used these scenarios to stretch thinking beyond business-as-usual assumptions, and analysed the implications for food production, consumption and land use.

Read more:

By changing our diets now, we can avoid the food chaos that climate change is bringing

The food system accounts for about a quarter of the emissions produced within the UK. This proportion will grow in the coming decades as energy, transport and buildings steadily decarbonise.

Our modelling yielded some inescapable home truths. We will need to change not just how we farm, but what farming produces and what we eat. And land use will need to change to strengthen carbon sequestration along with our ability to adapt to climate change. Three types of transformation are required.

First, strengthening the resilience of UK farming will require that farmers have a clear direction of travel, as they did after the second world war. Then, a technological revolution supported by guaranteed prices helped raised productivity. Now, adopting low-carbon technologies will only get us so far, and we will need to manage what is produced and consumed in a more joined up way, if we are to become less reliant on imports while freeing up some land for other vital uses.

Farm livestock production takes up 85% of agricultural land when growing animal feed is factored in. That limits the scope to strengthen the resilience of the system. Radically expanding horticultural production, for example, by growing more vegetables and salad crops could significantly improve our food self-sufficiency.

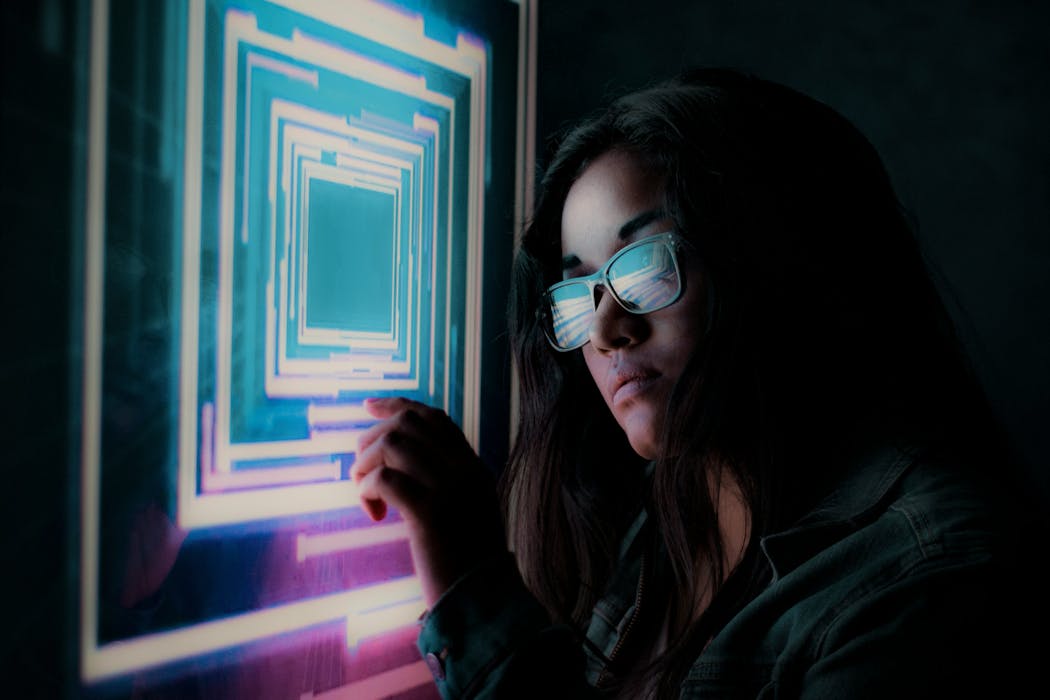

Juice Flair/Shutterstock

Second, farmers and landowners will be in the vanguard of sequestering carbon and helping the UK adapt to climate change through land use change – by planting trees and managing land to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The UK is much less wooded than the rest of Europe, but growing more native trees will bring benefits for farming, including shelter for animals and less soil erosion, and for rural economies through green jobs.

We need to more actively plan land-use change to better balance food production with other valuable environmental services from the land. For example, a more mixed and wooded farm landscape can reduce flood risk and water pollution. Smarter, more integrated land use means managing land for multiple benefits rather than narrow goals.

Third, encouraging dietary change can bring opportunities for growing and marketing new foodstuffs and help reduce the negative economic consequences of unhealthy diets. More fruit, vegetables and legumes are a win-win for people’s health and planetary sustainability, as the recent report from the EAT Lancet Commission demonstrated.

At a junction

Our network has produced a roadmap with phased measures through the 2020s, 2030s and 2040s.

In the two decades after the second world war, the UK food system transformed. Today, system-wide changes are happening in the energy and transport sectors. Now, it’s time to plan the transformation of our food system.

That starts with strengthening the resilience of our farming in the face of climate change and geopolitical uncertainties. Our three core transformations would bring social and economic benefits, improved public health and environmental quality – as well as a more diverse and attractive countryside.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 45,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

![]()

Neil Ward receives funding from UK Research and Innovation.

He is a member of the Labour Party and the National Trust.

– ref. Three ways to make the UK’s food system more resilient – according to new report by 150 experts – https://theconversation.com/three-ways-to-make-the-uks-food-system-more-resilient-according-to-new-report-by-150-experts-265603