Source: The Conversation – USA – By Anna Storti, Assistant Professor of Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies and Asian American Studies, Duke University

The Department of Homeland Security in September 2025 said that 2 million undocumented immigrants had been forced out of the United States since the start of Donald Trump’s second presidency.

Through its use of the Alien Enemies Act, a wartime law from 1798, the Trump administration has bypassed immigration courts and the right to due process to more easily detain and deport immigrants.

The Trump administration has, in part, reached these numbers by arresting immigrants in courthouses and at their workplaces. It has also conducted raids in schools, hospitals and places of worship.

And the Supreme Court in September, in its Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo decision, lifted a federal court order that barred agents with Immigration and Customs Enforcement from racially profiling suspected undocumented immigrants. For now, ICE agents can use race, ethnicity, language and occupation as grounds for stopping and questioning people.

This form of targeting has disproportionately affected Latino communities, which represent 9 in 10 ICE arrests, according to a UCLA study published in October.

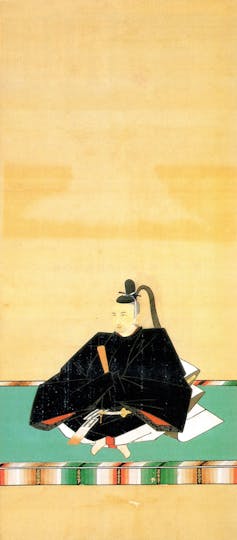

Targeting immigrants is a centuries-old American practice. In particular, Asian Americans have drawn parallels between the attacks on Latinos today and the forced relocation and incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.

Notably, the passage of the War Brides Act, passed just three months after the end of WWII, in December 1945, broke with the nation’s centuries-long practice of exclusionary immigration policy. The act allowed American servicemen to bring their non-American spouses and children to the United States. The measure seemed to inaugurate a new era of inclusive immigration policy.

As a feminist studies scholar and author, I know the War Brides Act forever altered the nation’s racial demographics, increasing both Asian migration to the U.S. and the birth of biracial children.

On the 80th anniversary of the War Brides Act, I’ve also noticed an alarming contradiction: Although America may be more multiracial than ever before, the U.S. immigration system remains as exclusive as it has ever been.

Exclusionary immigration policy

The racial profiling of Latino people by ICE agents today is not unlike what took place during World War II in the U.S.

Following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued an executive order authorizing the forced removal of anyone deemed to be a national security threat. Anyone, that is, who was Japanese. From 1942 to 1945, the U.S. government incarcerated approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans in internment camps.

To determine who was a national security threat, the government used overt racial profiling. Similar to today, when the U.S. government often misidentifies Latino Americans as noncitizens, a majority of the Japanese people incarcerated in WWII were U.S. citizens.

Amid the Trump administration’s treatment of immigrants, it’s worth recalling the exclusionary origins of U.S. immigration policy.

The first restrictive immigration law in the U.S., the Page Act of 1875, barred Chinese women from entering the country. The assumption the law was based on was that all Chinese women were immoral and worked in the sex trade.

Jacek Boczarski/Anadolu via Getty Images

The Page Act laid the groundwork for the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which banned all Chinese immigration into the U.S. for 10 years. This was the first federal law to ban an entire ethnic group, launching an era of legalized and targeted exclusion.

With the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924, the U.S. created its first border control service, which enforced new immigration restrictions. It also implemented a quota system, which banned or limited the number of immigrants from specific regions, including Asia and Southern and Eastern Europe.

The act stemmed from nativism – the policy that protects the interests of native-born residents against those of immigrants – and a desire to preserve American homogeneity.

The 1945 War Brides Act largely diverged from these previous measures, helping to dismantle the Asian exclusion made commonplace in the 19th and early 20th centuries. From 1945 until 1948, when the War Brides Act expired, more than 300,000 people entered the country as nonquota immigrants, people from countries not subject to federal immigration restrictions.

Exclusionary tendencies

Decades later, in 1965, the U.S. formally abolished the quota system. America opened its doors to those who President Lyndon B. Johnson deemed most able to contribute to the nation’s growth, particularly skilled professionals.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 eliminated racial exclusion. As a result, the U.S. population diversified. Immigrants deepened the multiracialism initiated by the War Brides Act.

This trend increased later in the 1960s when the Supreme Court, in Loving v. Virginia, overturned anti-miscegenation laws, which criminalized marriage between people of different races. The justices ruled that laws banning interracial marriage violated the 14th Amendment.

Multiracialism further increased after the Vietnam War. Subsequent legislation such as the 1987 Amerasian Homecoming Act facilitated the entry of biracial children born in Vietnam and fathered by a U.S. citizen.

© CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

By the 1960s, however, exclusion was taking on a different shape.

After 1965, immigration policy initiated a preference system that prioritized skilled workers and relatives of U.S. citizens. Quotas related to race and national origin were abolished. Nonetheless, preferences for families and professionals excluded people from Latin America.

For the first time, immigration from the Western Hemisphere was limited. This directly affected migrant workers in the farming and agricultural industries, many of whom were Latino.

Recalling the War Brides Act allows Americans to better comprehend the fiction that undergirds the U.S. immigration system: that immigration policy’s preference for certain immigrants is enough to justify the discriminatory policies which deem some families more valuable than others.

![]()

Anna Storti has received funding from the Institute for Citizens and Scholars, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and the McNair Scholars Program.

– ref. Racial profiling by ICE agents mirrors the targeting of Japanese Americans during World War II – https://theconversation.com/racial-profiling-by-ice-agents-mirrors-the-targeting-of-japanese-americans-during-world-war-ii-271612