Source: The Conversation – in French – By Stefan Wolff, Professor of International Security, University of Birmingham

Donald Trump a célébré la nouvelle année en marquant son territoire et en ouvrant la porte à un nouveau partage du monde entre Washington, Moscou et Pékin. L’Europe, tétanisée, prend acte par son silence approbateur de la mort du droit international.

Donald Trump et les hauts responsables de son administration ont salué l’opération « Détermination absolue » – le raid sur Caracas et la capture et l’enlèvement du président vénézuélien Nicolas Maduro, le 3 janvier 2026 – comme un succès militaire exceptionnel. On peut tout aussi aisément affirmer qu’il s’agit d’une violation flagrante et éhontée du droit international, qui marque une nouvelle érosion de ce qui reste de l’ordre international.

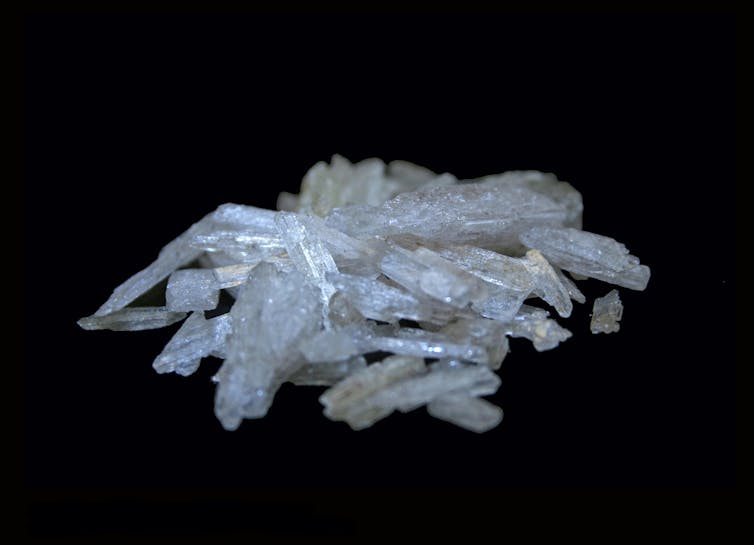

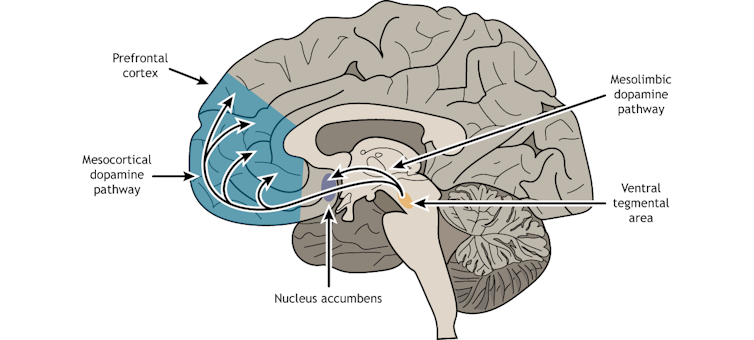

Mais la tentation pour la Maison Blanche est désormais de crier victoire et de passer rapidement à d’autres cibles, alors que le monde est encore sous le choc de l’audace dont a fait preuve le président américain en kidnappant un dirigeant étranger en exercice. Les populations et les dirigeants de Cuba (depuis longtemps une obsession pour le secrétaire d’État de Trump Marco Rubio), de Colombie (le plus grand fournisseur de cocaïne des États-Unis) et du Mexique (la principale voie d’entrée du fentanyl aux États-Unis) ont des raisons de s’inquiéter sérieusement pour leur avenir dans un monde trumpien.

Il en va de même pour les Groenlandais, en particulier à la lumière des commentaires de Trump ce week-end selon lesquels les États-Unis « ont besoin du Groenland du point de vue de leur sécurité nationale ». Sans parler du tweet alarmant de Katie Miller, influente membre du mouvement MAGA et épouse de Stephen Miller, l’influent chef de cabinet adjoint de Trump, montrant une carte du Groenland aux couleurs du drapeau américain.

Et ce n’est pas la réaction timide de la plupart des responsables européens qui freinera le président américain dans son élan. Celle-ci est extrêmement déconcertante, car elle révèle que les plus ardents défenseurs du droit international semblent avoir renoncé à prétendre qu’il a encore de l’importance.

La cheffe de la politique étrangère de l’Union européenne (UE), Kaja Kallas a été la première à réagir, avec un message qui commençait par souligner le manque de légitimité de Maduro en tant que président et se terminait par l’expression de sa préoccupation pour les citoyens européens au Venezuela. Elle a du bout des lèvres réussi à ajouter que « les principes du droit international et de la charte des Nations unies doivent être respectés ». Cette dernière partie apparaissait comme une réflexion après coup, ce qui était probablement le cas.

La déclaration commune ultérieure de 26 États membres de l’UE (soit tous les États membres sauf la Hongrie) était tout aussi équivoque et ne condamnait pas explicitement la violation du droit international par Washington.

Le premier ministre britannique Keir Starmer a pour sa part axé sa déclaration sur le fait que « le Royaume-Uni soutient depuis longtemps une transition au Venezuela », qu’il « considère Maduro comme un président illégitime » et qu’il « ne versera pas de larmes sur la fin de son régime ». Avant de conclure en exprimant son souhait d’une « transition sûre et pacifique vers un gouvernement légitime qui reflète la volonté du peuple vénézuélien », l’ancien avocat spécialisé dans les droits humains a brièvement réitéré son « soutien au droit international ».

Le chancelier allemand Friedrich Merz remporte toutefois la palme. Tout en faisant des commentaires similaires sur le défaut de légitimité de Maduro et l’importance d’une transition au Venezuela, il a finalement souligné que l’évaluation juridique de l’opération américaine était complexe et que l’Allemagne « prendrait son temps » pour le faire.

Le point de vue de Moscou et Pékin

Alors que l’Amérique latine était partagée entre enthousiasme et inquiétude, les condamnations les plus virulentes sont venues de Moscou et de Pékin.

Le président russe Vladimir Poutine avait manifesté son soutien à Maduro dès le début du mois de décembre. Dans une déclaration publiée le 3 janvier, le ministère russe des affaires étrangères se contentait initialement d’apporter son soutien aux efforts visant à résoudre la crise « par le dialogue ». Dans des communiqués de presse ultérieurs, la Russie a adopté une position plus ferme, exigeant que Washington « libère le président légitimement élu d’un pays souverain ainsi que son épouse ».

La Chine a également exprimé son inquiétude quant à l’opération américaine, la qualifiant de « violation flagrante du droit international ». Un porte-parole du ministère des affaires étrangères a exhorté Washington à « garantir la sécurité personnelle du président Nicolas Maduro et de son épouse, à les libérer immédiatement, à cesser de renverser le gouvernement du Venezuela et à résoudre les problèmes par le dialogue et la négociation ».

La position de Moscou, en particulier, est bien sûr profondément hypocrite. Certes condamner l’opération américaine comme étant une « violation inacceptable de la souveraineté d’un État indépendant » est peut-être justifié. Mais cela n’est guère crédible au vu de la guerre que Moscou mène depuis dix ans contre l’Ukraine, qui s’est traduite par l’occupation illégale et l’annexion de près de 20 % du territoire ukrainien.

La Chine, quant à elle, peut désormais avoir le beurre et l’argent du beurre à Taïwan, qui, contrairement au Venezuela, n’est pas largement reconnu comme un État souverain et indépendant. Le changement de régime apparaissant de nouveau à l’ordre du jour international comme une entreprise politique légitime, il ne reste plus grand-chose, du point de vue de Pékin, qui pourrait s’opposer à la réunification, si nécessaire par la force.

Les actions de Trump contre le Venezuela n’ont peut-être pas accéléré les plans chinois de réunification par la force, mais elles n’ont guère contribué à les dissuader. Cet épisode va probablement encourager la Chine à montrer plus d’assurance en mer de Chine méridionale.

Le partage du monde

Tout cela laisse présager un nouveau glissement progressif des intérêts des grandes puissances américaine, chinoise et russe, qui souhaitent disposer de sphères d’influence dans lesquelles elles peuvent agir à leur guise. Car si la Chine et la Russie ne peuvent pas faire grand-chose pour leur allié Maduro, désormais destitué, c’est aussi parce qu’il n’existe aucun moyen simple de délimiter où commence une sphère d’influence et où finit une autre.

La perspective d’un partage du monde entre Washington, Moscou et Pékin explique aussi l’absence d’indignation européenne face à l’opération menée par Trump contre le Venezuela. Elle témoigne de sa prise de conscience que l’ère de l’ordre international libre et démocratique est bel et bien révolue. L’Europe n’est pas en position d’adopter une posture qui lui ferait risquer d’être abandonnée par Trump et assignée à la sphère d’influence de Poutine.

Au contraire, les dirigeants européens feront tout leur possible pour passer sous silence leurs divergences avec les États-Unis et tenteront de tirer parti d’une remarque presque anodine faite par Trump à la fin de sa conférence de presse samedi 3 janvier, selon laquelle il n’est « pas fan » de Poutine.

Ce qui importe désormais pour l’Europe, ce ne sont plus les subtilités des règles internationales. Il s’agit dorénavant de garder les États-Unis et leur président imprévisible de son côté, dans l’espoir de pouvoir défendre l’Ukraine et de dissuader la Russie de commettre de nouvelles agressions.

Ces efforts pour accommoder le président américain ne fonctionneront que dans une certaine mesure. La décision de Trump de réaffirmer son ambition d’annexer le Groenland, dont il convoite les vastes ressources minérales essentielles, s’inscrit dans sa vision d’une domination absolue dans l’hémisphère occidental.

Cette renaissance de la doctrine Monroe vieille de deux siècles (rebaptisée par Trump « doctrine Donroe ») a été exposée dans la nouvelle stratégie de sécurité nationale américaine en décembre 2025. Elle ne s’arrête clairement pas au changement de régime au Venezuela.

La stratégie vise à « rétablir les conditions d’une stabilité stratégique sur le continent eurasien » ou à « atténuer le risque de conflit entre la Russie et les États européens ». Mais déstabiliser davantage l’alliance transatlantique en menaçant l’intégrité territoriale du Danemark au sujet du Groenland et en abandonnant peut-être l’Europe et l’Ukraine aux desseins impériaux du Kremlin risque d’avoir l’effet inverse.

De même, si l’incursion au Venezuela encourage les revendications territoriales chinoises en mer de Chine méridionale et éventuellement une action contre Taïwan, elle ne permettra guère d’atteindre l’objectif américain, énoncé dans la stratégie de sécurité nationale, qui consiste à prévenir une confrontation militaire avec son rival géopolitique le plus important.

À l’instar des autres tentatives de changement de régime menées par les États-Unis depuis la fin de la guerre froide, l’action américaine au Venezuela risque d’être une initiative qui isolera le pays et se retournera contre lui. Elle marque le retour de la loi de la jungle, pour laquelle les États-Unis, et une grande partie du reste du monde, finiront par payer un lourd tribut.

La traduction en français de cet article a été assurée par le site Justice Info.

![]()

Stefan Wolff a bénéficié par le passé de subventions du Conseil britannique de recherche sur l’environnement naturel, de l’Institut américain pour la paix, du Conseil britannique de recherche économique et sociale, de la British Academy, du programme « Science pour la paix » de l’OTAN, des programmes-cadres 6 et 7 et Horizon 2020 de l’UE, ainsi que du programme Jean Monnet de l’UE. Il est administrateur et trésorier honoraire de la Political Studies Association du Royaume-Uni et chercheur principal au Foreign Policy Centre de Londres.

– ref. Le raid de Donald Trump sur le Venezuela laisse présager un nouveau partage du monde entre les grandes puissances – https://theconversation.com/le-raid-de-donald-trump-sur-le-venezuela-laisse-presager-un-nouveau-partage-du-monde-entre-les-grandes-puissances-273026