Source: The Conversation – Canada – By Sara Karn, Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of History, McMaster University

In June 2015, 10 years ago, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) called for curriculum on Indigenous histories and contemporary contributions to Canada to foster intercultural understanding, empathy and respect. This was the focus of calls to action Nos. 62 to 65.

As education scholars, we are part of a project supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council called Thinking Historically for Canada’s Future. This project involves researchers, educators and partner organizations from across Canada, including Indigenous and non-Indigenous team members.

As part of this work, we examined Canadian history and social studies curricula in elementary, middle and secondary schools with the aim of understanding how they address — and may better address in future — the need for decolonization.

We found that although steps have been made towards decolonizing history curricula in Canada, there is still a long way to go. These curricula must do far more to challenge dominant narratives, prompt students to critically reflect on their identities and value Indigenous world views.

Read more:

Looking for Indigenous history? ‘Shekon Neechie’ website recentres Indigenous perspectives

Reimagining curriculum

As white settler scholars and educators, we acknowledge our responsibility to unlearn colonial ways of being and learn how to further decolonization in Canada.

In approaching this study, we began by listening to Indigenous scholars, such as Cree scholar Dwayne Donald. Donald and other scholars call for reimagining curriculum through unlearning colonialism and renewing relationships.

Read more:

Leaked Alberta school curriculum in urgent need of guidance from Indigenous wisdom teachings

The late Arapaho education scholar Michael Marker suggested that in history education, renewing relations involves learning from Indigenous understandings of the past, situated within local meanings of time and place.

History, social studies curricula

Curricula across Canada have been updated in the last 10 years to include teaching about treaties, Indian Residential Schools and the cultures, perspectives and experiences of Indigenous Peoples over time.

Thanks primarily to the work of Indigenous scholars and educators, including Donald, Marker, Mi’kmaw educator Marie Battiste, Anishinaabe scholar Nicole Bell and others, some public school educators are attentive to land-based learning and the importance of oral history.

But these teachings are, for the most part, ad hoc and not supported by provincial curriculum mandates.

Our study revealed that most provincial history curricula are still focused on colonial narratives that centre settler histories and emphasize “progress” over time. Curricula are largely inattentive to critical understandings of white settler power and to Indigenous ways of knowing and being.

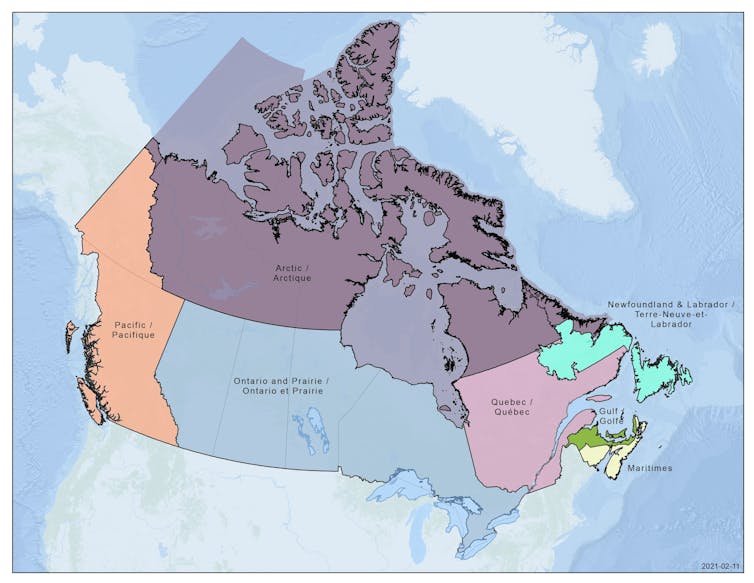

Notably, we do not include the three territories in this statement. Most of the territorial history curricula have been co-created with local Indigenous communities, and stand out with regard to decolonization.

For example, in Nunavut’s Grade 5 curriculum, the importance of local knowledge tied to the land is highlighted throughout. There are learning expectations related to survival skills and ecological knowledge.

Members of our broader research team are dedicated to analyzing curricula in Nunavut, the Northwest Territories and the Yukon. Their work may offer approaches to be adapted for other educational contexts.

Dominant narratives

In contrast, we found that provincial curricula often reinforce dominant historical narratives, especially surrounding colonialism. Some documents use the term “the history,” implying a singular history of Canada (for example, Manitoba’s Grade 6 curriculum).

Historical content, examples and guiding questions are predominantly written from a Euro-western perspective, while minimizing racialized identities and community histories. In particular, curricula often ignore illustrations of Indigenous agency and experience.

Read more:

Moving beyond Black history month towards inclusive histories in Québec secondary schools

Most curricula primarily situate Indigenous Peoples in the past, without substantial consideration for present-day implications of settler colonialism, as well as Indigenous agency and experiences today.

For example, in British Columbia’s Grade 4 curriculum, there are lengthy discussions of the harms of colonization in the past. Yet, there is no mention of the ongoing impacts of settler colonialism or the need to engage in decolonization today.

To disrupt these dominant narratives, we recommend that history curricula should critically discuss the ongoing impacts of settler colonialism, while centring stories of Indigenous resistance and survival over time.

Identity and privilege

There are also missed opportunities within history curricula when it comes to critical discussions around identity, including systemic marginalization or privilege.

Who we are informs how we understand history, but curricula largely does not prompt student reflection in these ways, including around treaty relationships.

In Saskatchewan’s Grade 5 curriculum, students are expected to explain what treaties are and “affirm that all Saskatchewan residents are Treaty people.”

However, there is no mention of students considering how their own backgrounds, identities, values and experiences shape their understandings of and responsibilities for treaties. Yet these discussions are essential for engaging students in considering the legacies of colonialism and how they may act to redress those legacies.

A key learning outcome could involve students becoming more aware of how their own personal and community histories inform their historical understandings and reconciliation commitments.

Indigenous ways of knowing and being

History curricula generally ignore Indigenous ways of knowing and being. Most curricula are inattentive to Indigenous oral traditions, conceptions of time, local contexts and relationships with other species and the environment.

Instead, these documents reflect Euro-western, settler colonial worldviews and educational values. For example, history curricula overwhelmingly ignore local meanings of time and place, while failing to encourage opportunities for land-based and experiential learning.

In Prince Edward Island’s Grade 12 curriculum, the documents expect that students will “demonstrate an understanding of the interactions among people, places and the environment.” While this may seem promising, environmental histories in this curriculum and others uphold capitalist world views by focusing on resource extraction and economic progress.

To disrupt settler colonial relationships with the land and empower youth as environmental stewards, we support reframing history curricula in ways that are attentive to Indigenous ways of knowing the past and relations with other people, beings and the land.

Ways forward

Schools have been, and continue to be, harmful spaces for many Indigenous communities, and various aspects of our schooling beg questions about how well-served both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students are for meeting current and future challenges.

If, as a society, we accept the premise that the transformation of current curricular expectations is possible for schools, then more substantive engagement is required in working toward decolonization.

Decolonizing curricula is a long-term, challenging process that requires consideration of many things: who sits on curriculum writing teams; the resources allocated to supporting curricular reform; broader school or board-wide policies; and ways of teaching that support reconciliation.

We encourage history curriculum writing teams to take up these recommendations as part of a broader commitment to reconciliation.

While not exhaustive, recommendations for curricular reform are a critical step in the future redesign of history curricula. The goal is a history education committed to listening and learning from Indigenous communities to build more inclusive national stories of the past, and into the future.

This is a corrected version of a story originally published June 17, 2025. The earlier story said Michael Marker was from the Lummi Nation instead of saying he was an Arapaho scholar.

![]()

Sara Karn receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC).

Kristina R. Llewellyn receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC).

Penney Clark receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC).

– ref. Decolonizing history and social studies curricula has a long way to go in Canada – https://theconversation.com/decolonizing-history-and-social-studies-curricula-has-a-long-way-to-go-in-canada-253679