Source: The Conversation – Global Perspectives – By Tom Lee, Senior Lecturer, School of Design, University of Technology Sydney

Australian farms are at the forefront of a wave of technological change coming to agriculture. Over the past decade, more than US$200 billion (A$305 billion) has been invested globally into the likes of pollination robots, smart soil sensors and artificial intelligence (AI) systems to help make decisions.

What do the people working the land make of it all? We interviewed dozens of Australian farmers about AI and digital technology, and found they had a sophisticated understanding of their own needs and how technology might help – as well as a wariness of tech companies’ utopian promises.

The future of farming

The supposed revolution coming to agriculture goes by several names: “precision agriculture”, “smart farming”, and “agriculture 4.0” are some of the more common ones.

These names all gesture towards a future in which the relationships between humans, computing and nature have been significantly reconfigured. Perhaps remote sensing technology will monitor ever more of a farm system, autonomous vehicles will patrol it, and AI will predict crop growth or cattle weight gain.

But there’s another story to tell about the way technological change happens. It involves people and communities creating their own future, their own sense of important change from the past.

AI, country style

Our research team conducted more than 35 interviews with farmers, specifically livestock producers, from across Australia.

The dominant themes of their responses were captured in two pithy quotes: “shit in, shit out” and “more automation, less features”.

“Shit in, shit out” is an earthier version of the “garbage in, garbage out” adage in computer science. If the data going into a model is unreliable or overly abstract, then the outputs will be shaped by those errors.

This captured a real concern for many farmers. They didn’t feel they could trust new technologies if they didn’t understand what knowledge and information they had been built with.

A different kind of automation

On the other hand, “more automation, less features” is what farmers want: technologies that may not have a lot of bells and whistles, but can reliably take a task off their hands.

Australian farmers have a ready appetite for labour-saving technologies. When human bodies are scarce, as they often are in rural Australia, machines are created to fill the void.

Windmills, wire fences, and even the iconic Australian sheepdog have been a crucial part of the technological narrative of settler colonial farming. These things are not “autonomous” in the same way as computer-powered vehicles and drones, but they offer similar advantages to farmers.

What these classic farm technologies have in common is a simplicity that derives from a clarity of purpose. They are the opposite of the “everything apps” that fuel the dreams of many Silicon Valley entrepreneurs.

“More automation, less features” is in this sense a farmer envisaging a digital product that fits with their image of a useful technology: transparent in its operations, and a reliable replacement for or an addition to human labour.

The lesson of the Suzuki Sierra Stockman

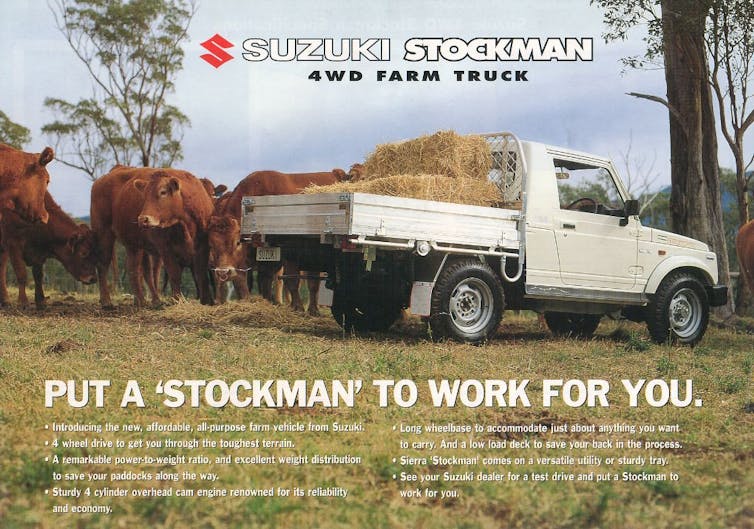

When speaking with one farmer about favoured technologies of her lifetime, she mentioned the Suzuki Sierra Stockman. These small, no-frills, four-wheel-drive vehicles became something of an icon on Australian sheep and cattle farms through the 1970s, ‘80s and ’90s.

Turbo_J / Flickr

Reflecting on her memories of first using the vehicle, the farmer said:

Once I learnt that I could actually draft cattle out with the Suzuki, that changed everything. You could do exactly what you did on a horse with a vehicle.

It seems unlikely that Suzuki’s engineers in Japan envisaged their little jeep chasing cattle in the paddocks of Central West of NSW. The Suzuki was in a sense remade by farmers who found innovative uses for it.

Future technology must be simple, adaptable and reliable

The combustion engine was a key technological change on farms in the 20th century. Computers may play a similar role in the 21st.

We are perhaps yet to see a digital product as iconic as wire fences, windmills, sheepdogs and the Suzuki Stockman. Computers are still largely technologies of the office, not the paddock.

However, this is changing as computers get smaller and are wired into water tanks, soil monitors and in-paddock scales. More data input from these sensors means AI systems have more scope to help farmers make decisions.

AI may well become a much-loved tool for farmers. But that journey to iconic status will depend as much on how farmers adapt the technology as on how the developers build it. And we can guess at what it will look like: simple, adaptable and reliable.

![]()

This article is based on research conducted by the Foragecaster project, led by AgriWebb and supported by funding from Food Agility CRC Ltd, funded under the Commonwealth Government CRC Program. The CRC Program supports industry-led collaborations between industry, researchers and the community. This project was also supported by funding from Meat and Livestock Australia (MLA).

– ref. ‘Shit in, shit out’: AI is coming for agriculture, but farmers aren’t convinced – https://theconversation.com/shit-in-shit-out-ai-is-coming-for-agriculture-but-farmers-arent-convinced-259997