Source: The Conversation – USA – By Amirali Aghazadeh, Assistant Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology

When NASA scientists opened the sample return canister from the OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample mission in late 2023, they found something astonishing.

Dust and rock collected from the asteroid Bennu contained many of life’s building blocks, including all five nucleobases used in DNA and RNA, 14 of the 20 amino acids found in proteins, and a rich collection of other organic molecules. These are built primarily from carbon and hydrogen, and they often form the backbone of life’s chemistry.

For decades, scientists have predicted that early asteroids may have delivered the ingredients of life to Earth, and these findings seemed like promising evidence.

Even more surprising, these amino acids from Bennu were split almost evenly between “left-handed” and “right-handed” forms. Amino acids come in two mirror-image configurations, just like our left and right hands, called chiral forms.

On Earth, almost all biology requires the left-handed versions. If scientists had found a strong left-handed excess in Bennu, it would have suggested that life’s molecular asymmetry might have been inherited directly from space. Instead, the near-equal mixture points to a different story: Life’s left-handed preference likely emerged later, through processes on Earth, rather than being pre-imprinted in the material delivered by asteroids.

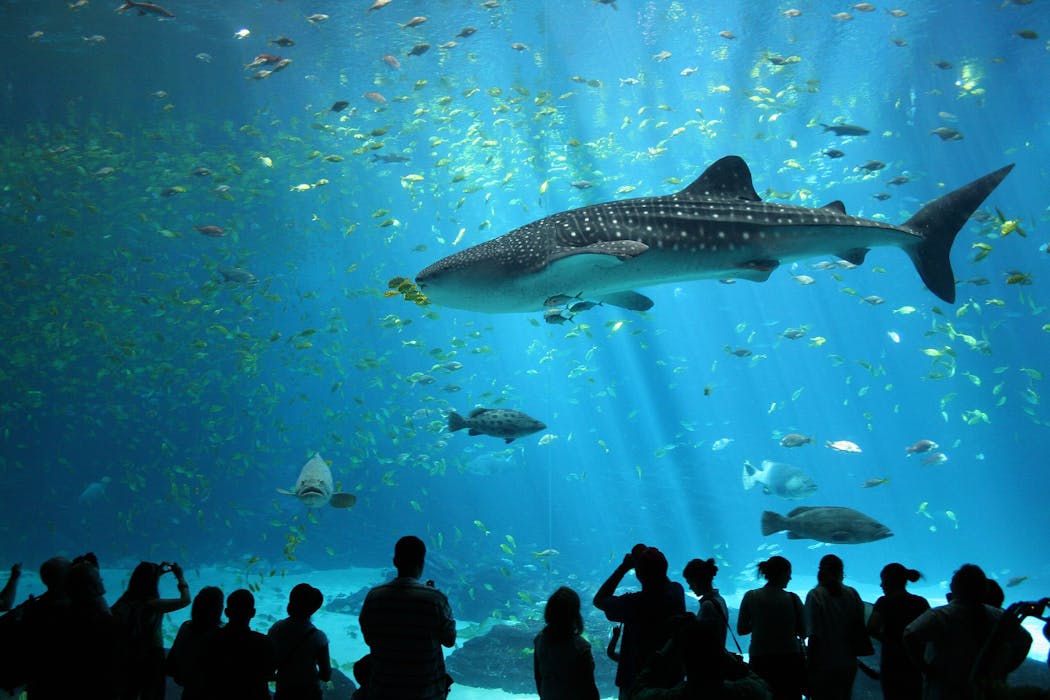

NASA

If space rocks can carry familiar ingredients but not the chemical “signature” that life leaves behind, then identifying the true signs of biology becomes extremely complicated.

These discoveries raise a deeper question – one that becomes more urgent as new missions target Mars, the Martian moons and the ocean worlds of our solar system: How do researchers detect life when the chemistry alone begins to look “lifelike”? If nonliving materials can produce rich, organized mixtures of organic molecules, then the traditional signs we use to recognize biology may no longer be enough.

As a computational scientist studying biological signatures, I face this challenge directly. In my astrobiology work, I ask how to determine whether a collection of molecules was formed by complex geochemistry or by extraterrestrial biology, when exploring other planets.

In a new study in the journal PNAS Nexus, my colleagues and I developed a framework called LifeTracer to help answer this question. Instead of searching for a single molecule or structure that proves the presence of biology, we attempted to classify how likely mixtures of compounds preserved in rocks and meteorites were to contain traces of life by examining the full chemical patterns they contain.

Identifying potential biosignatures

The key idea behind our framework is that life produces molecules with purpose, while nonliving chemistry does not. Cells must store energy, build membranes and transmit information. Abiotic chemistry produced by nonliving chemical processes, even when abundant, follows different rules because it is not shaped by metabolism or evolution.

Traditional biosignature approaches focus on searching for specific compounds, such as certain amino acids or lipid structures, or for chiral preferences, like left-handedness.

These signals can be powerful, but they are based entirely on the molecular patterns used by life on Earth. If we assume that alien life uses the same chemistry, we risk missing biology that is similar – but not identical – to our own, or misidentifying nonliving chemistry as a sign of life.

The Bennu results highlight this problem. The asteroid sample contained molecules familiar to life, yet nothing within it appears to have been alive.

To reduce the risk of assuming these molecules indicate life, we assembled a unique dataset of organic materials right at the dividing line between life and nonlife. We used samples from eight carbon-rich meteorites that preserve abiotic chemistry from the early solar system, as well as 10 samples of soils and sedimentary materials from Earth, containing the degraded remnants of biological molecules from past or present life. Each sample contained tens of thousands of organic molecules, many present in low abundance and many whose structures could not be fully identified.

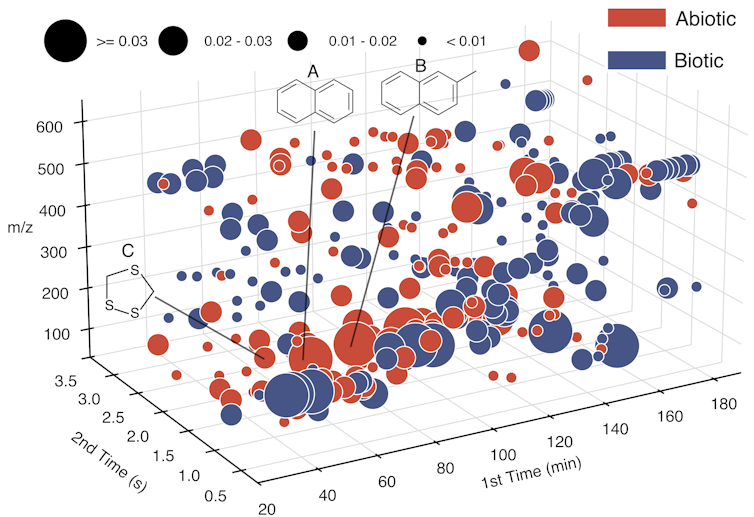

At NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, our team of scientists crushed each sample, added solvent and heated it to extract the organics — this process is like brewing tea. Then, we took the “tea” containing the extracted organics and passed it through two filtering columns that separated the complex mixture of organic molecules. Then, the organics were pushed into a chamber where we bombarded them with electrons until they broke into smaller fragments.

Traditionally, chemists use these mass fragments as puzzle pieces to reconstruct each molecular structure, but having tens of thousands of compounds in each sample presented a challenge.

LifeTracer

LifeTracer is a unique approach for data analysis: It works by taking in the fragmented puzzle pieces and analyzing them to find specific patterns, rather than reconstructing each structure.

It characterizes those puzzle pieces by their mass and two other chemical properties and then organizes them into a large matrix describing the set of molecules present in each sample. It then trains a machine learning model to distinguish between the meteorites and the terrestrial materials from Earth’s surface, based on the type of molecules present in each.

One of the most common forms of machine learning is called supervised learning. It works by taking many input and output pairs as examples and learns a rule to go from input to output. Even with only 18 samples as those examples, LifeTracer performed remarkably well. It consistently separated abiotic from biotic origins.

What mattered most to LifeTracer was not the presence of a specific molecule but the overall distribution of chemical fingerprints found in each sample. Meteorite samples tended to contain more volatile compounds – they evaporate or break apart more easily – which reflected the type of chemistry most common in the cold environment of space.

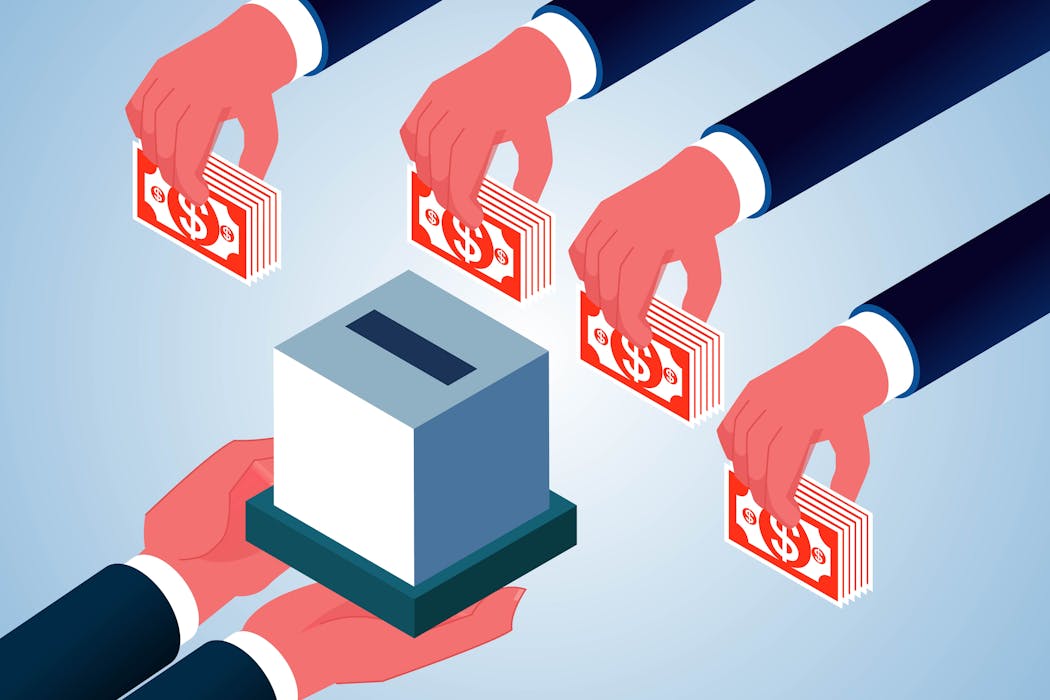

Saeedi et al., 2025, CC BY-NC-ND

Some types of molecules, called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, were present in both groups, but they had distinctive structural differences that the model could parse. A sulfur-containing compound, 1,2,4-trithiolane, emerged as a strong marker for abiotic samples, while terrestrial materials contained products formed through biological process.

These discoveries suggest that the contrast between life and nonlife is not defined by a single chemical clue but by how an entire suite of organic molecules is organized. By focusing on patterns rather than assumptions about which molecules life “should” use, approaches like LifeTracer open up new possibilities for evaluating samples returned from missions to Mars, its moons Phobos and Deimos, Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus.

Keegan Barber/NASA via AP

Future samples will likely contain mixtures of organics from multiple sources, some biological and some not. Instead of relying only on a few familiar molecules, we can now assess whether the whole chemical landscape looks more like biology or random geochemistry.

LifeTracer is not a universal life detector. Rather, it provides a foundation for interpreting complex organic mixtures. The Bennu findings remind us that life-friendly chemistry may be widespread across the solar system, but that chemistry alone does not equal biology.

To tell the difference, scientists will need all the tools we can build — not only better spacecraft and instruments, but also smarter ways to read the stories written in the molecules they bring home.

![]()

Amirali Aghazadeh receives funding from Georgia Tech.

– ref. Can scientists detect life without knowing what it looks like? Research using machine learning offers a new way – https://theconversation.com/can-scientists-detect-life-without-knowing-what-it-looks-like-research-using-machine-learning-offers-a-new-way-271066