Source: The Conversation – USA – By Alexey A. Petrov, Professor of physics and astronomy, University of South Carolina

Scientists working with the James Webb Space Telescope discovered three unusual astronomical objects in early 2025, which may be examples of dark stars. The concept of dark stars has existed for some time and could alter scientists’ understanding of how ordinary stars form. However, their name is somewhat misleading.

“Dark stars” is one of those unfortunate names that, on the surface, does not accurately describe the objects it represents. Dark stars are not exactly stars, and they are certainly not dark.

Still, the name captures the essence of this phenomenon. The “dark” in the name refers not to how bright these objects are, but to the process that makes them shine — driven by a mysterious substance called dark matter. The sheer size of these objects makes it difficult to classify them as stars.

As a physicist, I’ve been fascinated by dark matter, and I’ve been trying to find a way to see its traces using particle accelerators. I’m curious whether dark stars could provide an alternative method to find dark matter.

What makes dark matter dark?

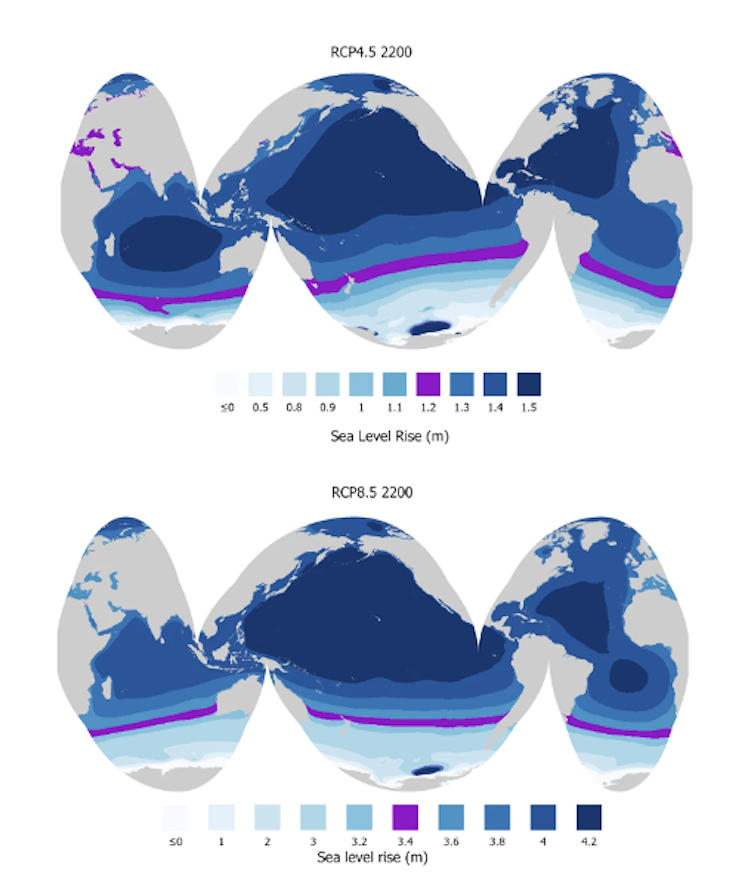

Dark matter, which makes up approximately 27% of the universe but cannot be directly observed, is a key idea behind the phenomenon of dark stars. Astrophysicists have studied this mysterious substance for nearly a century, yet we haven’t seen any direct evidence of it besides its gravitational effects. So, what makes dark matter dark?

Visual Capitalist/Science Photo Library via Getty Images

Humans primarily observe the universe by detecting electromagnetic waves emitted by or reflected off various objects. For instance, the Moon is visible to the naked eye because it reflects sunlight. Atoms on the Moon’s surface absorb photons – the particles of light – sent from the Sun, causing electrons within atoms to move and send some of that light toward us.

More advanced telescopes detect electromagnetic waves beyond the visible spectrum, such as ultraviolet, infrared or radio waves. They use the same principle: Electrically charged components of atoms react to these electromagnetic waves. But how can they detect a substance – dark matter – that not only has no electric charge but also has no electrically charged components?

Although scientists don’t know the exact nature of dark matter, many models suggest that it is made up of electrically neutral particles – those without an electric charge. This trait makes it impossible to observe dark matter in the same way that we observe ordinary matter.

Dark matter is thought to be made of particles that are their own antiparticles. Antiparticles are the “mirror” versions of particles. They have the same mass but opposite electric charge and other properties. When a particle encounters its antiparticle, the two annihilate each other in a burst of energy.

If dark matter particles are their own antiparticles, they would annihilate upon colliding with each other, potentially releasing large amounts of energy. Scientists predict that this process plays a key role in the formation of dark stars, as long as the density of dark matter particles inside these stars is sufficiently high. The dark matter density determines how often dark matter particles encounter, and annihilate, each other. If the dark matter density inside dark stars is high, they would annihilate frequently.

What makes a dark star shine?

The concept of dark stars stems from a fundamental yet unresolved question in astrophysics: How do stars form? In the widely accepted view, clouds of primordial hydrogen and helium — the chemical elements formed in the first minutes after the Big Bang, approximately 13.8 billion years ago — collapsed under gravity. They heated up and initiated nuclear fusion, which formed heavier elements from the hydrogen and helium. This process led to the formation of the first generation of stars.

NASA, ESA, CSA, and STScI, J. DePasquale (STScI), CC BY-ND

In the standard view of star formation, dark matter is seen as a passive element that merely exerts a gravitational pull on everything around it, including primordial hydrogen and helium. But what if dark matter had a more active role in the process? That’s exactly the question a group of astrophysicists raised in 2008.

In the dense environment of the early universe, dark matter particles would collide with, and annihilate, each other, releasing energy in the process. This energy could heat the hydrogen and helium gas, preventing it from further collapse and delaying, or even preventing, the typical ignition of nuclear fusion.

The outcome would be a starlike object — but one powered by dark matter heating instead of fusion. Unlike regular stars, these dark stars might live much longer because they would continue to shine as long as they attracted dark matter. This trait would make them distinct from ordinary stars, as their cooler temperature would result in lower emissions of various particles.

Can we observe dark stars?

Several unique characteristics help astronomers identify potential dark stars. First, these objects must be very old. As the universe expands, the frequency of light coming from objects far away from Earth decreases, shifting toward the infrared end of the electromagnetic spectrum, meaning it gets “redshifted.” The oldest objects appear the most redshifted to observers.

Since dark stars form from primordial hydrogen and helium, they are expected to contain little to no heavier elements, such as oxygen. They would be very large and cooler on the surface, yet highly luminous because their size — and the surface area emitting light — compensates for their lower surface brightness.

They are also expected to be enormous, with radii of about tens of astronomical units — a cosmic distance measurement equal to the average distance between Earth and the Sun. Some supermassive dark stars are theorized to reach masses of roughly 10,000 to 10 million times that of the Sun, depending on how much dark matter and hydrogen or helium gas they can accumulate during their growth.

So, have astronomers observed dark stars? Possibly. Data from the James Webb Space Telescope has revealed some very high-redshift objects that seem brighter — and possibly more massive — than what scientists expect of typical early galaxies or stars. These results have led some researchers to propose that dark stars might explain these objects.

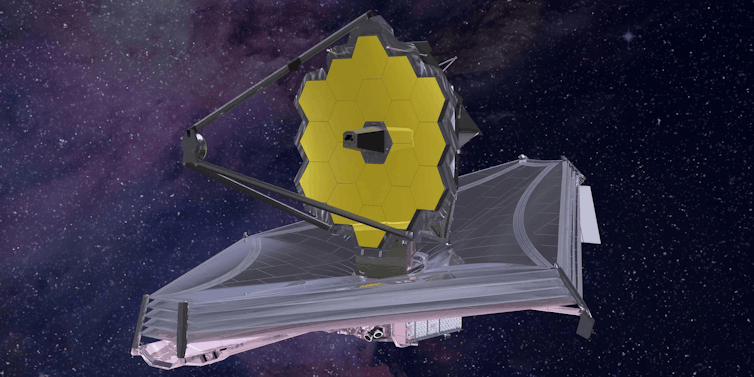

Northrup Grumman/NASA

In particular, a recent study analyzing James Webb Space Telescope data identified three candidates consistent with supermassive dark star models. Researchers looked at how much helium these objects contained to identify them. Since it is dark matter annihilation that heats up those dark stars, rather than nuclear fusion turning helium into heavier elements, dark stars should have more helium.

The researchers highlight that one of these objects indeed exhibited a potential “smoking gun” helium absorption signature: a far higher helium abundance than one would expect in typical early galaxies.

Dark stars may explain early black holes

What happens when a dark star runs out of dark matter? It depends on the size of the dark star. For the lightest dark stars, the depletion of dark matter would mean gravity compresses the remaining hydrogen, igniting nuclear fusion. In this case, the dark star would eventually become an ordinary star, so some stars may have begun as dark stars.

Supermassive dark stars are even more intriguing. At the end of their lifespan, a dead supermassive dark star would collapse directly into a black hole. This black hole could start the formation of a supermassive black hole, like the kind astronomers observe at the centers of galaxies, including our own Milky Way.

Dark stars might also explain how supermassive black holes formed in the early universe. They could shed light on some unique black holes observed by astronomers. For example, a black hole in the galaxy UHZ-1 has a mass approaching 10 million solar masses, and is very old – it formed just 500 million years after the Big Bang. Traditional models struggle to explain how such massive black holes could form so quickly.

The idea of dark stars is not universally accepted. These dark star candidates might still turn out just to be unusual galaxies. Some astrophysicists argue that matter accretion — a process in which massive objects pull in surrounding matter — alone can produce massive stars, and that studies using observations from the James Webb telescope cannot distinguish between massive ordinary stars and less dense, cooler dark stars.

Researchers emphasize that they will need more observational data and theoretical advancements to solve this mystery.

![]()

Alexey A Petrov receives funding from the US Department of Energy.

– ref. When darkness shines: How dark stars could illuminate the early universe – https://theconversation.com/when-darkness-shines-how-dark-stars-could-illuminate-the-early-universe-266971